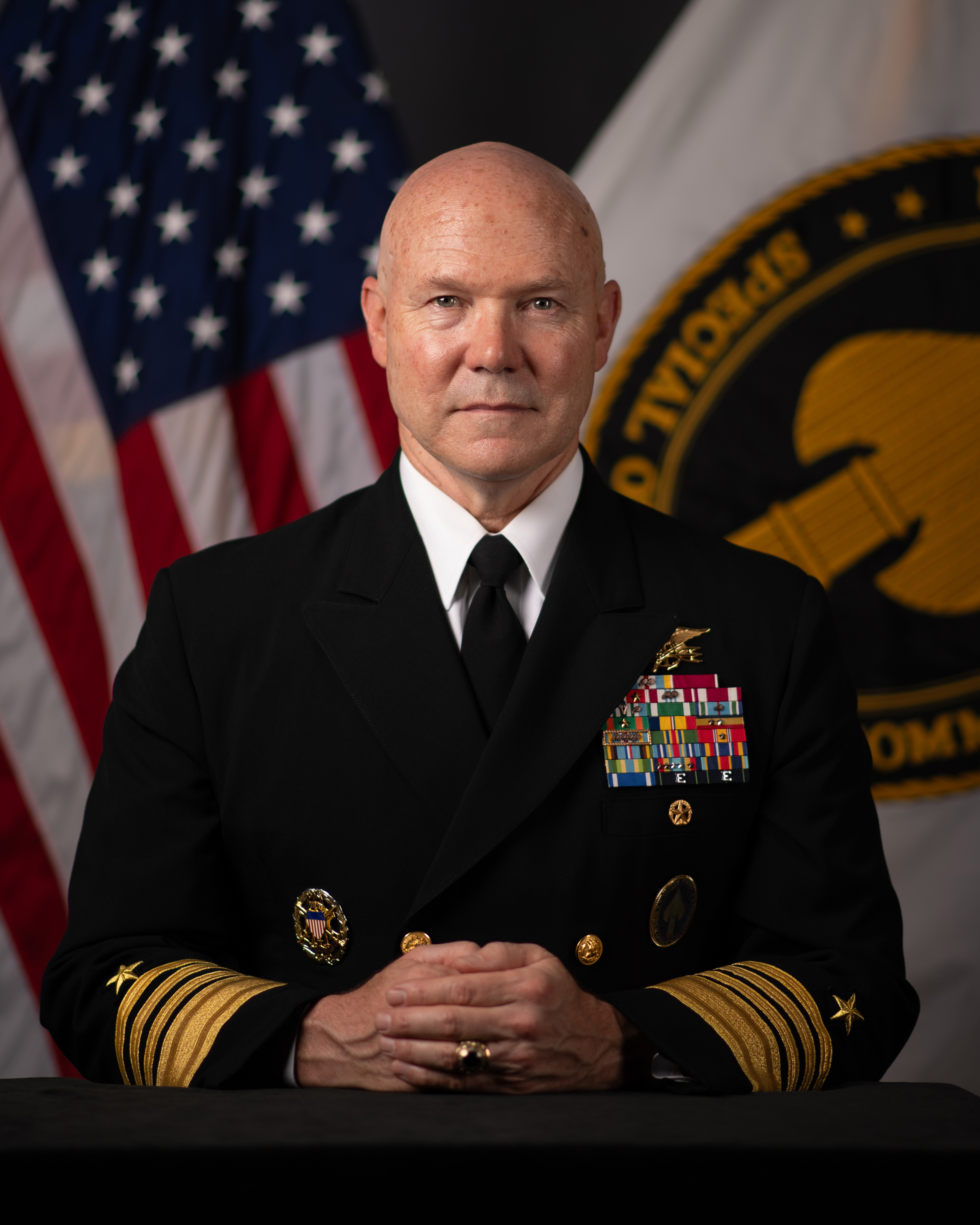

Admiral Frank M. Bradley has been the Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) since October 2025. Originally from Eldorado, Texas, ADM Bradley is a 1991 graduate of the United States Naval Academy. He has commanded at all levels of special operations, including Joint Special Operations Command, Special Operations Command Central, and Naval Special Warfare Development Group. He has multiple tours in command of joint task forces and was among the first to deploy into Afghanistan following the attacks of September 11, 2001.

CTC: You have been working CT for more than two decades. When you reflect on how the United States engaged in CT when you first became a SEAL to how the United States engages in CT today, what stands out to you?

Bradley: The increased cooperation between our integrated interagency and our allies and partners is quite remarkable. That increased cooperation was driven by our failure to see and disrupt the 9/11 attacks, but I believe this cooperation, coupled with the vigilance of our local and federal law enforcement enterprise is the reason there has not been a repeat attack of that nature. A second clear distinction is the increased trust/reliance that our elected and appointed civilian leaders have in the integrated interagency and SOCOM team. That trust is now empowered with a deeper understanding and knowledge of the art of the possible. We are more effective today at accomplishing our CT mission than we ever have been.

CTC: What is the toughest CT issue or challenge you have had to navigate through over the course of your career?

Bradley: The importance of truly working “By, Through and With” the local security forces of a region to defeat a terrorist organization is an important challenge. In the early years of the CT campaigns, we levered indigenous elements to support our largely unilateral efforts. Over time we realized that—to accomplish our mission—we would have to turn the territory over to that indigenous element to hold the security we had established. After a decade, the D-ISIS campaign in Iraq and Syria (2014-2019) and the C-al Shabaab efforts in Somalia (2010-2015) demonstrated an approach that was both illuminated and successful. The organizational inertia against “letting go” and trusting a partner force to own the solution was no small challenge. I am proud of our leaders who came to recognize the importance of this priority and those who led through it to achieve today’s sustainable CT approach—with our allies and partners in the lead. Our empowerment and occasional acute action to render a particularly dangerous threat will remain a part of that sustainable approach, but it is far more economical—and effective—than it ever has been.

CTC: There is an idea that JNIM and/or al-Shabaab could potentially be encouraged to follow a path or model similar to the Afghan Taliban or new Syrian government, which could limit the type of regional and extraterritorial threats that these two movements pose in the future. What do you think of this idea?

Bradley: JNIM and al-Shabaab are ideologically salafi-jihadist terror groups with clear political goals including territorial control and governance of their countries. If they are willing to prioritize those tangible political goals over salafi-jihadist terrorism and agree to renounce violence as their principal approach to governance, there could be opportunity to address the terror threat through engagement or diplomacy. The new Syrian government rejected ideological hostility to the West, providing more room for cooperation. Before JNIM or al-Shabaab can follow the same path as the Taliban or the al-Sharaa government in Syria, the groups would need to reconsider their relationships with the wider salafi-jihadist movement.

CTC: The issue of adversarial convergence has been a Department of War area of concern, and there are unfortunately a lot of examples where we see concerning interactions and cooperation between America’s state and non-state adversaries. Which areas concern you the most? Is there a vignette that stands out?

Bradley: Adversarial convergence challenges us when it creates a simultaneity problem—forcing the U.S. to prioritize limited resources against multiple facets of disparate, multi-domain threats. Additionally, alignment enables an adversary to offset their own shortfalls, which may then challenge us with new capabilities. For example, the Houthis, enabled by Iran, presented a threat to freedom of navigation in the Red Sea. Then, the Houthis began providing advanced weaponry and training to al-Shabaab. This further complicates freedom of navigation, threatens the safety of global commerce and U.S. military operations, all while increasing the demand for limited forces in the same region. The Russian/Iranian interdependencies are of interest as well. On the one hand, the Iranians have buttressed the Russian inadequacies on the battlefields of Ukraine, and though the Russians continue to lose their soldiers at an astounding rate, the mass of low-cost weapons the Iranians are providing them has allowed the Russians to remain active. Meanwhile, the Iranians have mortgaged their people’s future and prosperity by funding the Russian’s military adventure. While the short-term nature of these cooperative activities is prolonging the suffering of millions—on the battlefield and off—it is also providing the most stark example of the failures of their governance models. Ultimately, this collaboration will hasten their collective strategic failure.

CTC: What terrorist groups concern you the most today and what groups do you see having the potential to emerge as a homeland threat in the future?

Bradley: VEOs and terrorism remain a consistent and persistent threat, and both ISIS and al-Qa`ida are improving their ability to attack U.S. interests. At least two affiliates—al-Qa`ida in Yemen and ISIS-Khorasan—have the potential to emerge as a homeland threat and continue to seek to inspire, enable, and direct attacks. Both groups maintain strong ideological motivations to attack the United States and are drawing on ample recruits and funding while becoming more technological savvy.

Outside of VEOs, transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) and drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in Mexico, Latin America, and South America represent an escalating threat to the homeland as well. These organizations are seeking to expand their revenue streams and tighten their grip on critical smuggling routes to the U.S. to deliver drugs that are killing Americans at an alarming rate. To do this, they use violence, coercion, and bribery to undermine governments and the rule of law.

CTC: The United States and its partners continue to place a lot of pressure on Islamic State networks in Syria and Iraq, and in Somalia. For example, in mid-September U.S. forces along with Iraqi counterparts, killed Omar Abdul Qader, who served as the Islamic State’s head of operations and external security. How would you characterize the current state and threat posed by the Islamic State ecosystem, and how the United States has been trying to combat it?

Bradley: Both the current state of and the threat from the Islamic State is degraded compared to when it held territory … but it is a persistent one. While the physical caliphate was eliminated, as you note, ISIS continues to adapt. Progress against ISIS in one area is often undermined by ISIS expansion in another. For example, the loss of Omar Abdul Qader left ISIS in Iraq severely weakened and our Iraqi allies are effectively degrading its remnants. Unfortunately, the Islamic State is also expanding into West Africa, which then allowed another affiliate to assume a greater leadership role for the Islamic State enterprise. In other areas, like Afghanistan and Pakistan, the DRC, Mozambique, Somalia, and Syria, we see ISIS affiliates that endure episodic periods of increased CT pressure, and then immediately begin to regenerate lost capability when that CT pressure wanes. While not all those regions pose direct threats to the U.S., they are all still working together as part of a common enterprise and we do see them providing each other mutual support to various degrees. While not every Islamic State affiliate has the intent to attack the homeland, they all work together to provide those groups who do with access to more resources and capability than they would have had otherwise.

CTC: One of the first things that President Trump did once in office was designate six Mexican cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs). This has raised questions about the potential role of special operations forces to combat them. How is the SOF enterprise thinking about this issue? What are some of the key considerations we need to navigate? What advantages does SOF bring to bear if used in the fight against these entities and how can SOF lead the CT enterprise through this new challenge?

Bradley: The designation of Mexican cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) by President Trump has sparked significant discussions about the role of SOF in combating these entities. One key consideration is the need for a comprehensive approach that integrates intelligence, direct action, and support to local forces. This approach was exemplified in the U.S. Plan Colombia, where SOF played a crucial role in training and advising Colombian military and police forces, enhancing their capabilities to combat drug trafficking and insurgent groups. Plan Colombia yielded significant outcomes, including a substantial reduction in coca cultivation and cocaine production, as well as the weakening of major insurgent groups like the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia).

The success of Plan Colombia demonstrates the advantages SOF can bring to bear, such as specialized training, operational flexibility, and the ability to build strong partnerships with host nation forces. By leveraging these strengths, SOF can effectively contribute to the counterterrorism enterprise in addressing the threats posed by these newly designated cartels.

CTC: Increasingly, we are seeing the proliferation of drone use as a weapon in asymmetric conflict by terrorist groups against their adversaries—from Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) fighters targeting the Nigerian military1 and Houthis striking inside Israel2 to their use recently by a drug-trafficking militia in Colombia in downing a police Blackhawk helicopter.3 From your vantage point, how do weaponized drones in the hands of non-state actors and terrorist groups change the calculus for special operations? What concerns do you have about overcoming this threat vector?

Bradley: The proliferation of weaponized drones to non-state actors and VEOs presents a significant challenge for special operations forces. Weaponized drones provide non-state actors and VEOs a new capability that holds U.S. protection at risk and gives the enemy battlefield advantages never seen before. Until very recently, the ability to exploit the aerial domain and leverage it for a range of missions, including surveillance and attack, was limited to nation-states. Now, someone with a few thousand dollars and access to the internet can order a drone that takes high-resolution images and modify it to drop explosives. These drones also give threat groups the ability to pose a more significant threat to a wider target set in their operating areas. For example, the recent disruptions to airport operations in Europe demonstrate the ability of even unarmed drones to pose a real challenge.

SOCOM recognizes the critical need to stay ahead of such evolving threats and prioritizes innovation to counter these challenges. By fostering a culture of innovation and leveraging cutting-edge technology, SOCOM aims to maintain a strategic advantage over VEOs and non-state actors alike. A key aspect of this strategy involves working closely with partners to find effective solutions. Events like SOF Weeka play a crucial role in this collaborative effort, bringing together military leaders, industry experts, and international allies to share knowledge, develop new technologies, and enhance interoperability. By emphasizing partnerships and collective problem-solving, SOCOM ensures that it remains at the forefront of countering the threats posed by weaponized drones.

CTC: Technology is revolutionizing warfare and lowering barriers to entry to key types of tech—from drones to artificial intelligence, and 3D printing—and capabilities for terrorist groups and radicalized individuals. How is the U.S. CT community evolving and modernizing to meet the threat and enhancing or developing new CT capabilities to stay ahead of these challenges?

Bradley: We need to operationalize the notion of disruptive technology and use it to deter future war. We need to recreate a team of industry, academia, defense, warfighters, and the various ecosystems inside the United States. We need to recognize that to deter war today and avoid a future war, we must be able to meet those challenges of the day. Technological change is outpacing our procurement cycles. Our markets are innovating faster in many important areas than the pace of our contracting offices or of those acquisition cycles. Information is no longer the guarded property of governments alone. It is ubiquitous, crowdsourced, and exploitable by anyone with a will to look. Our adversaries in many cases adapt in weeks, leveraging the state of the market, not the state of the art.

While we transform over years with our traditional acquisition approach, those gaps, that gap in time and in pace of innovation, is a risk that can become existential. The time for us to evolve this system is now. Our challenge is to adapt before that existential threat presents itself and evolves into a crisis. We have to evolve ahead of the threat, ride the wave of technological change, and not be overrun by it.

CTC: Less resources have been devoted to CT over the past several years. This has meant that key resources or some tools that have been used for CT are now more focused on other problems and priorities. One area where this has been felt is the domain of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR),4 which has been a core aspect of modern CT operations. This has pushed the CT community to prioritize, innovate, and get more creative, but in some ways the issue remains a key constraint, as legacy ISR platforms still hold a lot of utility. How do you think about this dilemma and the pathway through it?

Bradley: The reduction in resources devoted to CT over the past several years has followed the reduction of the scope of the terrorist organizations. Airborne ISR has and always will be a key part of our tool kit, but increasingly, we are able to leverage the virtual domain to help us understand terrorist intent, plans, and coordination activities. With less resources being devoted to CT, SOCOM seeks to empower our partners and allies to achieve shared security objectives through their own use of both the increasingly available small UAS physical domain ISR as well as their own exploitation of the virtual domain as well. We accomplish this through platforms such as Operation Gallant Phoenix, which brings together military and law enforcement personnel of 32 countries to better understand and respond to current and evolving CT threats.

CTC: When you look forward and scan the near-term horizon to the future of terrorism, what are you concerned about? What gives you hope?

Bradley: Looking forward, I’m concerned that the underlying conditions that allowed groups like al-Qa`ida and ISIS to emerge still exist across much of the world. In many regions, the conditions don’t just persist, they’re getting worse, further exacerbated by world events like the Gaza crisis and poor governance driven by the Iranian influence across the Middle East. This creates a large and growing population susceptible to radicalization. Advanced technologies like cheap smart phones also make it easier for extremist groups to connect with these vulnerable populations and then direct them at us. As the world changes, my greatest concern is the rapidly accelerating ability of bad actors to connect and enable individuals with the capabilities to do outsized damage. My balancing hope is in the ever-resilient Western alliance of freedom-loving peoples who are more interconnected and complementary than ever. We are stronger together, and our cooperation is the bulwark against the ills of instability. CTC

Substantive Notes

[a] “Held in Tampa, Florida, Special Operations Forces (SOF) Week is an annual conference for the international SOF community to learn, connect, and honor its members. Jointly sponsored by USSOCOM and the Global SOF Foundation, the 2025 edition attracted over 19,000 in-person attendees.” See https://sofweek.org/

Citations

[1] Abiodun Jamiu, “Nigeria: ISWAP Extremists Launching Attack Drones,” Deutsche Welle, April 16, 2025.

[2] Abby Rogers, “Suspected Houthi Drone Attack Strikes Israeli City of Eilat,” Al Jazeera, September 18, 2025.

[3] Juan Forero, “Police Helicopter Downed by Drone in Colombia, Killing 12,” Wall Street Journal, August 21, 2025.

[4] “Senate Armed Services Committee Hearing on Posture of USCENTCOM and USAFRICOM in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for FY24 and the Future Years Defense Program.”

Skip to content

Skip to content