Abstract: Some recent terrorist activities in Europe, including a foiled plot against Belgium’s prime minister, have purposefully aimed at elected officials. This is not a new phenomenon, as there is a long tradition of political assassinations among terrorist groups. However, there are some indications that this may be the start of a new era of political violence against state representatives. This study analyzes data on terrorist attacks against European elected officials over the past decade. It concludes that there is a persistent threat, dominated by far-right violent extremism. While the data does not allow one to conclude that the threat is growing in Europe, the study highlights some significant trends that could result in higher threat levels against government officials.

On October 9, 2025, three young individuals were arrested near Antwerp, Belgium, for allegedly planning a terrorist attack inspired by jihadi ideology. Their plot looked ambitious, involving improvised explosives carried by a commercial drone. It also contrasted drastically with most low-scale contemporary terrorist attacks perpetrated by lone actors. Most importantly, the small cell was allegedly targeting the Belgian prime minister, Bart De Wever, and possibly other political figures.1

Several politicians have been the target of terrorism in recent years. Prominent examples include the assassination and attempted murder of state representatives in Minnesota in June 2024 by a Christian abortion opponent.2 In May 2024, a man shot and critically injured Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico and was convicted for terrorism in October 2025.3 In October 2021, Member of the U.K. Parliament David Amess was stabbed to death, by a self-identified member of the Islamic State who was subsequently convicted in relation to terrorism.4 In June 2019, German regional governor Walter Lübcke was shot dead by a far-right extremist opposing pro-immigration policy. The perpetrator was convicted to a life sentence, although not on the basis of terrorism charges.5 In November 2017, a man associated with the Islamic State had plotted to kill U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May. He was arrested in a successful police operation and convicted to life in prison for terrorism.6

These are just some recent—and highly mediatized—cases of violent attacks on elected officials, qualified as terrorism or violent extremism. This article explores whether this is a new wave of terrorist threats against political leaders, reminiscent of previous eras of political assassinations, by looking at the frequency of such plots. It reflects more broadly on the context and causes behind attacks against elected officials.

Some recent research has investigated politically motivated violent attacks against elected and other government officials in the United States, clearly showing a growing occurrence of such incidents.7 This article explores whether a similar trend is observed in other regions, namely Europe, and whether this phenomenon can be attributed to terrorism and violent extremism.

The article starts by placing terrorist attacks against political figures in a broader historical perspective. It then presents and analyzes a new dataset of terrorist attacks against elected officials in Europe (2015-2025). The article concludes with a discussion of whether the current security and political contexts could result in a growing trend of attacks against elected officials.

Historical Precedents in Europe

Terrorism directed at state representatives is not new. Terrorist groups have long considered it legitimate to assassinate heads of state and other prominent political figures to advance their agenda. After all, the term terrorism originates from the so-called “Reign of Terror,” the brief period that followed the French Revolution in the late 18th century marked by brutal political violence, resulting notably in the beheading of King Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, and several other prominent figures.8

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, anarchists heralded a never-equaled period of regicides, killing the Russian Tsar Alexander II (1881), French President Sadi Carnot (1894), Spanish Prime Minister Canovas del Castillo (1897), Austrian Empress Elisabeth (1898), King Umberto I of Italy (1900), and U.S. President William McKinley (1901). The same period also witnessed several near misses on other heads of state, including Belgian King Leopold II.9

The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in Sarajevo (1914) is yet another prominent example. The assassin was a member of a nationalist organization from Serbia, ‘the Black Hand,’ which can be described as a terrorist group. This act famously precipitated World War I.

The second half of the 20th century saw several other prominent illustrations of terrorist groups targeting political leaders. In 1961 and 1962, two assassination attempts narrowly missed French President Charles De Gaulle. The perpetrators of those attempts were members of the far-right terror group Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), which resisted the French withdrawal from Algeria through terror campaigns.10

On the other side of the political spectrum, the far-left Italian terrorist group Red Brigades kidnapped former Prime Minister Aldo Moro in 1978, asking for the release of some prisoners in exchange. After 55 days of captivity, Moro was executed.11

Ethno-separatist organizations were not left out. In 1973, the Basque separatist terror organization ETA killed Spanish Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco in a spectacular bombing.12 In 1984, the Irish separatist organization IRA nearly succeeded in killing British Prime Minister Thatcher, in an even more daring hotel bombing in Brighton, which resulted in five deaths, including a conservative MP, and dozens of injured.13

Several prominent examples outside Europe could also be mentioned. This includes notably the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981 by the Egyptian Islamic Jihad and of India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1984, killed by Sikh extremists.

This short and non-exhaustive list of prominent attacks demonstrates a long tradition of terrorist groups resorting to political assassinations. As argued by one scholar, over time a growing number of terrorist groups have come to “see assassination as a legitimate and effective tool.”14

In this regard, one can confidently assert that plots like the one foiled in Belgium are not a new phenomenon. It is, in fact, a recurring terrorist tactic, across time and ideologies. But is it on the rise? The next section leverages a dataset to address this question as it pertains to Europe.

Data Collection

There is no harmonized dataset on politically motivated attacks against elected officials in Europe. Although some countries collect and publish relevant data (see below), this is more the exception than the rule. Furthermore, similarly to the U.S. studies mentioned above, the data rarely distinguishes between terrorism, violent extremism, and more broadly politically motivated incidents. As a result, existing data is insufficient to paint a clear picture across Europe. It also prevents a more nuanced analysis of the phenomenon focused on terrorism and violent extremism, as opposed to all types of violent crimes, against elected officials.

To address this issue, the author collected data on incidents covering the past decade (2015-2025)—a sufficiently long period to observe significant trends.a The geographical focus of this data collection effort was exclusively limited to European countries, including E.U. countries, as well as the United Kingdom and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland).b This selection offers some reasonable geographical and political consistency, as these countries are all liberal democracies (although some countries arguably less than others) in a situation of peace.c

The dataset focuses on terrorism and the broader concept of ‘violent extremism.’ The question of what constitutes a terrorist attack is a recurring element of discussion around any dataset in this field.15 One restrictive solution is to adhere to prosecutorial decisions (i.e., to collect only cases that resulted in a conviction for terrorism offenses). However, this is largely unsatisfactory for several reasons. First, even within a coherent geographical area, terrorism laws and their concrete implementation can vary greatly, hence possibly introducing a significant bias. Indeed, some countries have a significantly higher threshold for prosecuting terrorist offenses, compared to others. Second, some ideologies, namely jihadi, are more likely to result in terrorist convictions than others, due to the explicit recognition of the terrorist nature of groups such as al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State. Third, a number of attacks or plots are never prosecuted either because the perpetrator died in the attack or the perpetrator(s) managed to escape justice.

To build the dataset, therefore, the author relied on the broader scholarly understanding of terrorism, based on several decades of research. The dataset includes attacks that were clearly motivated by a violent ideology, as evidenced either by the perpetrator’s profile (e.g., member of a terrorist organization) or discourse (e.g., promoting violent extremist views). Cases that did not hew closely to the general understanding of terrorism and violent extremism, and did not meet these criteria, were excluded.16 d

Although legal thresholds are not a panacea, they do constitute an interesting criteria nonetheless. In spite of the caveats mentioned above, cases leading to terrorism convictions can be considered—under certain circumstances—as more serious than those that do not and are therefore worth particular attention. As a result, the data distinguishes between ‘terrorism cases,’ resulting in convictions for terrorism offenses, and ‘violent extremism cases,’ when individuals were either not arrested or not convicted for terrorism (although sometimes they had been charged with terrorism, but the charges were eventually dropped). Finally, some cases were categorized as ‘unclear,’ when information was lacking on the incident and its perpetrator(s), but there was still sufficient information (related to the context, for example) to justify considering the incident as likely motivated by terrorism or violent extremism. To be clear, the distinction between “terrorism” and “violent extremism” in this case is more legalistic than conceptual, as all cases included in the dataset are considered by this author as a form of terrorism in the sense of the scholarly literature. In cases where the author had doubt, the incident was excluded from the dataset.

The threshold for inclusion is much higher compared to some previous research that included more broadly defined threats and harassment against politicians. Online harassment and threats are a highly problematic issue and can undermine democracy, however, such a low threshold across this study’s geographical area would have likely resulted in thousands of results, representing very different types of events and motivations. A systematic data collection would have been further complicated since most of these types of threats are not reported to the police, and even less so prosecuted.17 Overall, the narrow focus on terrorism and violent extremism creates more data coherence and is more insightful for the field of terrorism studies.

The dataset includes completed and failed attacks as well as foiled plots. This is in line with the observation by other scholars that terrorism plots should be included when possible to provide a more complete measure of terrorist activity and trends.18 However, the inclusion of plots challenges any claim to the comprehensiveness of the dataset. Indeed, while a number of terror plots leak to the press, presumably even more so when involving prominent political figures, it is also fair to assume that many more plots remain unknown. Foiled plots are much less visible, particularly if they were low profile or disrupted at an early stage. As a result, a number of these plots do not get much media coverage, if at all, particularly if they did not lead to public charges and prosecution. Aside from two exceptions, the dataset includes only foiled plots that resulted in the prosecution of the perpetrator(s), and hence resulted in some media coverage.

With regard to the targets, the dataset includes plots and attacks against all elected officials and political representatives—whether at the local, national or international levels—in the European countries outlined above. This includes local council officials or mayors, members of parliament or governments, as well as members of the European Parliament. Compared to other studies that focus on a broader category of ‘public officials’ (including, for example, education, health workers, or law enforcement), which more broadly represent the government,19 this study aligns more closely with the work of other scholars who have focused on a narrower and more coherent corpus of state representatives: elected officials.20

Finally, several sources were leveraged to build the dataset. This included searches through major databases and annual reports on terrorism such as the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), the Right-Wing Terrorism and Violence (RTV) Dataset, and Europol’s annual Terrorism Situation and Trends Report (TE-SAT) reports on terrorism trends in Europe. It also included searches through academic articles covering this topic and queries that used a combination of key words run through Google and LexisNexis.e Some snowball research was also implemented, as some articles were referring to other cases that were subsequently researched.f

Results

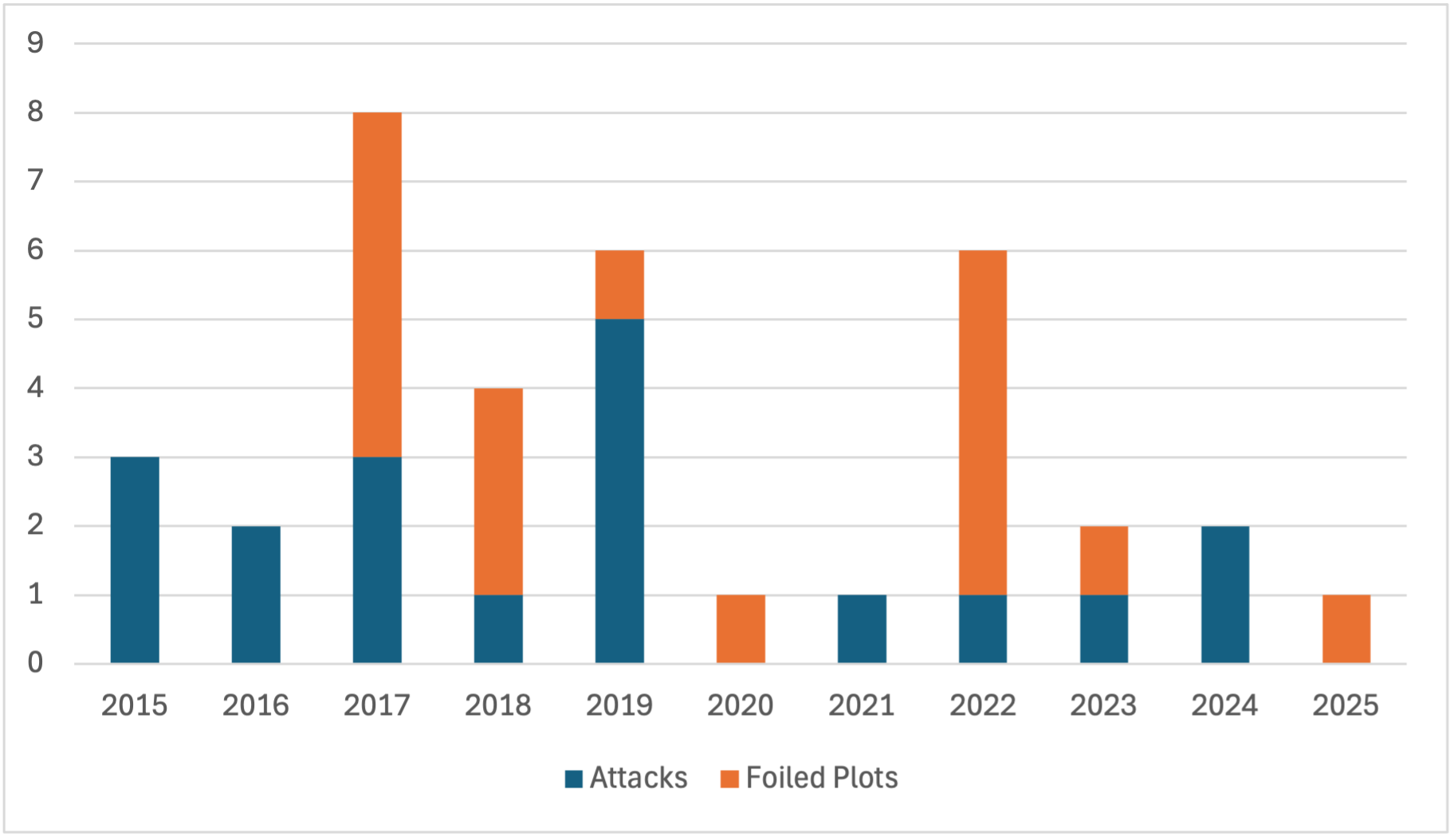

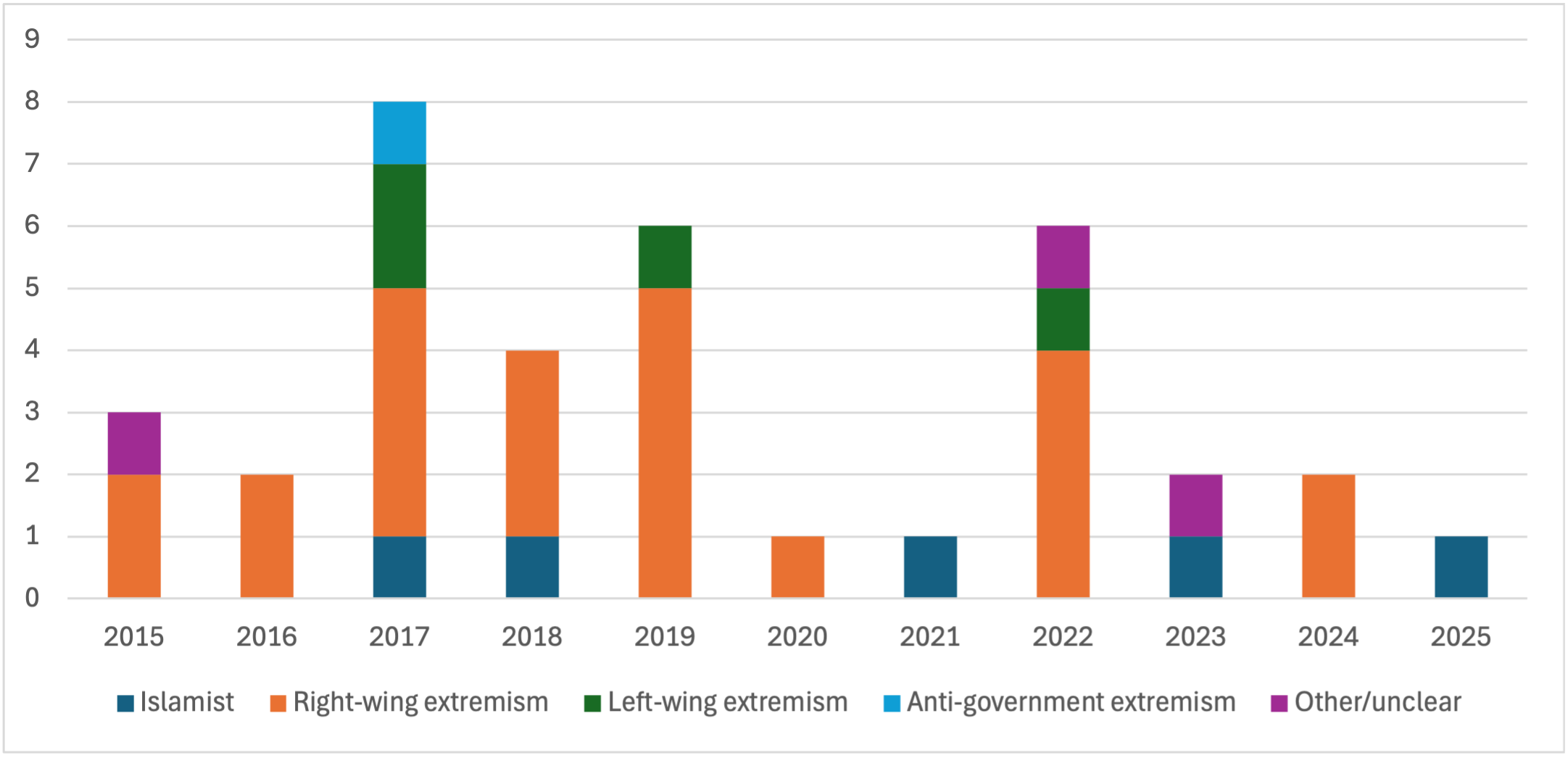

The dataset contains 36 ideologically motivated attacks or plots against European elected officials from 2015-2025. This includes 19 completed attacks and 17 foiled plots. Specifically, the dataset includes 15 terrorist incidents,g 17 violent extremist incidents, and four unclear cases. As explained above, the “violent extremist” incidents and the “unclear cases” would fit most scholarly definitions of terrorism, but did not result in a conviction for a terrorist offense and were therefore coded separately for transparency.

As a preliminary remark, it is important to note that while the dataset provides valuable insights, the small number of cases in the dataset (N=36) prevents drawing definitive conclusions, and the findings should therefore be interpreted with caution. Despite efforts to ensure comprehensiveness, it is likely that additional relevant cases were not captured, which could meaningfully alter the observed patterns. The results should thus be seen as indicative rather than conclusive, highlighting preliminary findings and potential areas for further research.

A first interesting observation is that there does not seem to be a clear trend of increasing attacks or plots by terrorist actors against elected officials in Europe. On the contrary, if anything, there is a slightly decreasing trend. The majority of the attacks are concentrated in the years 2017-2019 and 2022. There were 23 incidents in the period 2015-2019, compared with 13 incidents in the period 2020-2025. This would suggest a fairly stable phenomenon, rather than a growing trend in terrorism tactics. The years 2020 and 2021 include only one incident each. This low occurrence could be explained by the successive lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, which decreased the time available for conducting attacks, although it could also be the result of data randomness.

Another interesting issue is that the majority (seven out of 13) of the incidents that occurred since 2020 are coded as terrorism.h In comparison, only a third of the incidents during the period 2015-2019 were coded as terrorism. Since the number of terrorist incidents is similar between both periods (eight incidents in 2015-2019, seven incidents in 2020-2025), the distinction is linked to a variation in violent extremism rather than terrorism incidents. Thus, if there is actually a slight decrease of political violence against elected officials in Europe, it is to be found in the lower spectrum of violent activities (i.e., plots/attacks that did not result in terrorist convictions) rather than in the higher spectrum (i.e., plots/attacks that resulted in convictions for terrorism offense).

With regard to ideology, the majority of the attacks (64%) were linked to far-right extremism. The rest were jihadi attacks, left-wing extremism, one case of anti-government extremism, one case of state terrorism, and two cases that could not be clearly categorized (but were likely left-wing extremism). The persistence of attacks from far-right extremists over time is quite striking. While one would have logically expected a spike during the so-called ‘refugees crisis’ in 2015-2017, when over a million asylum-seekers entered Europe to flee the war in Syria and Iraq, far-right extremist attacks actually peaked in 2019. In contrast, the quasi absence of anti-government extremist attacks in the dataset is similarly remarkable, particularly as one would have expected such attacks during and just after the COVID pandemic.

In spite of these counter-intuitive observations, context clearly plays a role in the dataset. Indeed, several attacks were motivated by the broader discussions on immigration, in Germany and in the United Kingdom notably.i Other attacks were also closely connected with important political decisions or electoral contexts, occurring in a highly polarized setting.j However, while the socio-political context clearly influences specific cases and likely overall terrorism trends, the dataset is too small and too limited to draw significant conclusions in this regard, as mentioned above.

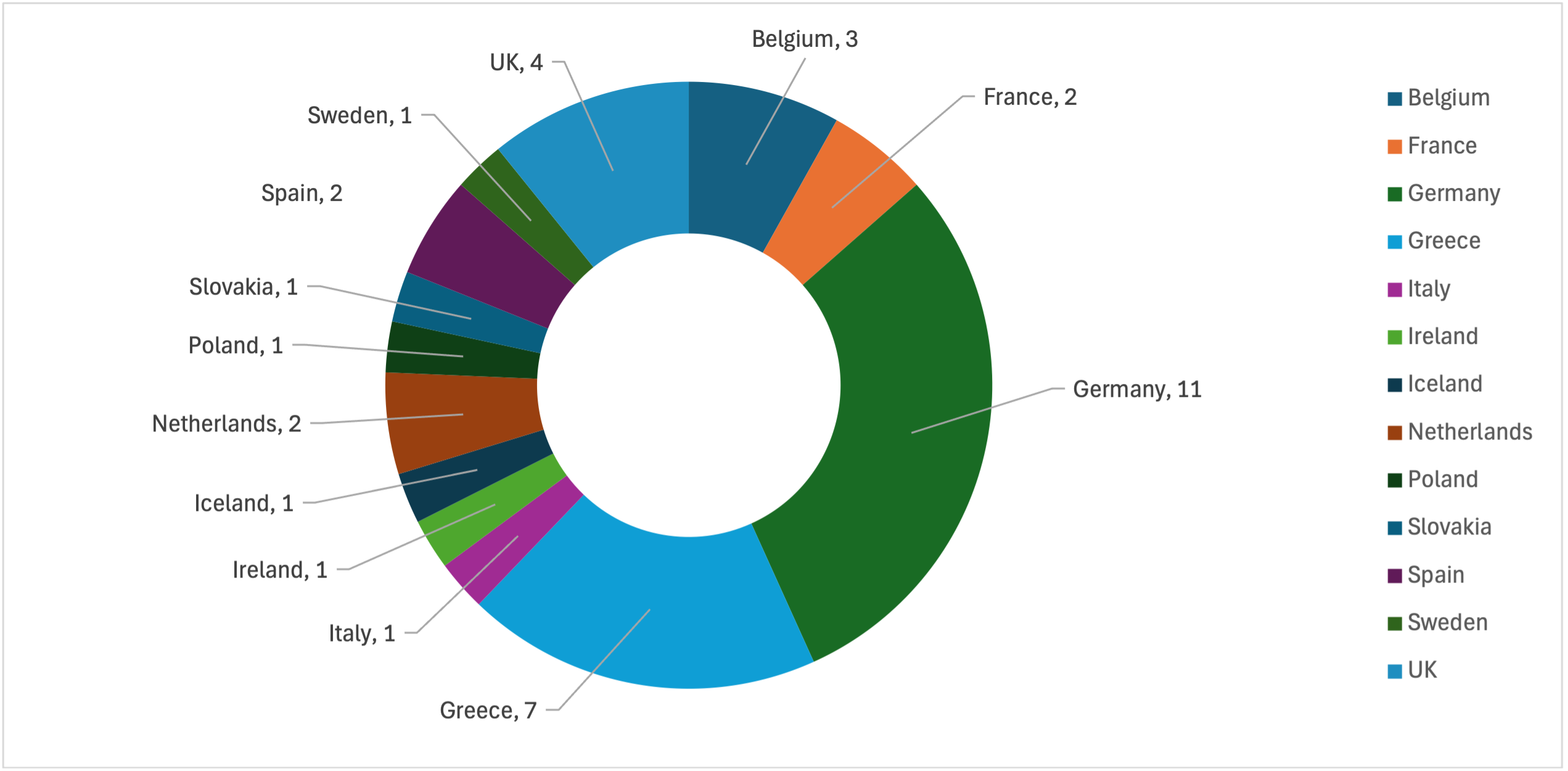

Geographically, Germany is by far the most impacted country in the dataset, suffering 30% of the attacks. While this certainly raises questions, it could be explained by at least two elements. First, Germany is the largest country in Europe in terms of population, but also possibly in terms of elected officials.k Second, this might correlate with the fact that most attacks in the dataset originate from the far-right, since Germany is the European country with the largest far-right milieu with nearly 40,000 far-right extremists according to intelligence services, of which roughly a third is categorized as potentially violent.21 In contrast, the preponderance of incidents in Greece (7) is slightly more surprising, although the activities of the left-wing and right-wing extremist milieus in the country are well documented.22

Regarding targets, the dataset suggests that national officials (63% of the incidents) are more exposed than local or international ones. To some extent, this is counter-intuitive since there are far more local than national elected officials across Europe. However, this could be explained by the larger salience of national targets (due to their media exposure), and the larger potential impact resulting from such attacks (in terms of media coverage). There could also possibly be a media reporting bias, as it cannot be excluded that attacks on local politicians receive less media attention—although the author was unable to verify this possible bias.

It is also notable that male politicians dominate the list of targets, as the dataset includes almost three times more male than female targets. However, this might be a mere reflection of the gender bias in politics, as men are overrepresented among elected officials.

Finally, it is worth noting that several officials appear more than once in the dataset, in spite of the small size of the sample. Two politicians appear twice (one Belgian, one Greek), and one Dutch politician appears three times in the dataset.

A New Era of Political Assassinations?

If terrorist attacks against European elected officials were fairly stable over the past decade, could things take a new turn? Could the terrorist plot against Belgian Prime Minister De Wever be the beginning of a new era of political assassinations? There are certainly some reasons to fear so.

To begin with, elected officials remain a core target of terrorist groups. It is clear that jihadi groups consider the leaders of enemy governments as legitimate targets. The same holds true for a good part of the far-leftl and of the far-right. For instance, Norwegian far-right terrorist Anders Breivik had identified political leaders as priority targets in his 1,500-page manifesto, which remains highly influential within far-right communities to this day.23 In Northern Ireland, a far-right group calling itself the “New Republican Movement” published a video in November 2025 in which it deemed local elected representatives “legitimate targets” due to their pro-immigration policies.24

The evolution of the broader terrorist landscape, which has been for some time dominated by lone actors as opposed to larger networks, provides one additional explanation for fearing a new era of political assassinations. Indeed, while seemingly on the rise across Europe, the terrorist threat has changed drastically compared to a decade ago.25 Today’s terrorist threat in Europe mostly comes from young isolated individuals, radicalized online, with limited connections to a terrorist group’s leadership, if any, and virtually no combat skills.26 This reality contrasts heavily with the big terrorist networks active in Europe between 2014-2017, which were trained and tasked by the Islamic State’s leadership to cause mayhem on the continent.

Under this new reality, large-scale terrorist attacks are less likely, because they require a network, and demand time and resources to organize—in other words, they are mostly beyond reach for lone actors.m In contrast, smaller terrorist acts, such as stabbing attacks, are becoming the norm in Europe. Because these acts lack the dramatic impact of large attacks, lone offenders often try to compensate by choosing their targets more carefully. For individuals acting on their own, without a clear link to a larger terrorist campaign or network, it becomes even more important to ensure their attack sends a strong signal. In terrorism strategy, the so-called “propaganda of the deed” holds that the act itself—including the choice of target—is meant to communicate a message to a wider audience. The selection of targets is therefore critical to shaping a clear and unmistakable message.

As argued by Petter Nesser in his seminal book on jihadi terrorism in Europe, during periods of fragmented terrorist networks, as at the turn of the first decade of the 2000s, terrorist actors turn more naturally toward symbolic targets such as religious communities, minorities (e.g., LGBTQI+ or immigrants), or state representatives (e.g., police or elected officials)—as opposed to random and indiscriminate attacks.27 The careful selection of these symbolic targets is a necessity to draw attention and spread the terrorist message wider.

A slightly different but related explanation can be found in the work of terrorism scholar Arie Perliger: Terrorist actors may resort to political assassination when they feel that other tactics have failed or are unlikely to produce the desired outcomes, or when they have less resources.28 Indeed, political assassination is comparatively ‘cheap’ when compared to larger attrition campaigns and offers a ‘quick win’ in terms of visibility and highlighting the government’s vulnerability.

Moreover, in the context of a resurging trend of state-sponsored terrorism, and active hybrid warfare in Europe, it is not far-fetched to imagine that threats against certain politicians are already on the rise and could increase further.

Besides the general terrorism landscape in Europe, which could influence the attractiveness of elected officials as targets for terrorist actors, there is another notable trend that appears at play. Although data is only fragmentary, there are strong indications that elected officials are increasingly victims of threats and violence generally, and not just in relation to terrorism.29 Indeed, the majority of these threats remain below the threshold of terrorism and violent extremism, despite often also being politically motivated. This is very likely the result of a growing polarization of societies, which results notably in a seemingly rising popular support for violence against elected officials. Some recent polls and studies suggest that a growing number of citizens believe that violence can be considered acceptable to achieve political goals, which could include violence against elected officials. This certainly seems to be the case in the United States,30 but could also be a trend in Europe.31

In Germany, the federal police (BKA) has registered a steady yearly increase of politically motivated crimes against state representatives (+262% between 2019 and 2024, from 1,673 to 6,059 crimes). Among these, the proportion of violent crimes against state representatives has also increased by 37% during the same period, reaching 122 violent attacks in 2024. The police data is corroborated by polls and studies showing that German local officials are increasingly subject to threats and violence.32

In France, similarly, local elected officials have been confronted with a growing number of threats and aggressions, rising from 1,716 reported cases in 2021 to 2,501 in 2024 (+46%). The number of cases involving physical violence also increased, reaching 250 attacks in 2024. This trend was considered serious enough that a new law was adopted in 2024 to better protect local elected officials.33

In the Netherlands, a 2024 report surveyed 1,082 decentralized political office holders on personal experiences with aggression and violence. It found that 45% of them encountered some form of aggression in the past year, which is up from 33% in 2020 and 23% in 2014.34

In Belgium, a poll conducted in 2023 among 483 local elected officials found that 18% had been the target of violence and of physical threats (up to 28% of the mayors).35 Meanwhile, the number of public figures under police protection following threats has almost doubled between 2016 and 2024, reaching 101 individuals in 2025 according to the National Crisis Centre.36

In Norway, a study surveyed a number of politicians to ask about their exposure to threats and violence. In 2021, 36% of the members of the cabinet and parliament surveyed had received threats to themselves or close family members, an increase compared to similar surveys conducted in 2017 and 2013.37

Data from the United States points to an even more remarkable spike of threats against elected officials. A team of researchers from the University of Chicago compiled all charged acts of violence or threats of violence against members of the Congress since 2001, at federal and state levels, and noted a 600% increase between President Obama’s second term and the first Trump administration (2017-2020), with a clear spike between 2016 and 2017 (+400%), and a continuous yearly increase until reaching an all-high in 2021, and stabilizing at a high level since.38 Interestingly, these threats are divided equally between Democratic and Republican members of Congress. Another study focused on federal charges regarding threats against public officials in the United States finds a similar sharp increase since 2017, reflecting in part a rise in ideologically motivated threats.39 In their conclusions, the authors of the latter study also make some interesting observations, including the fact that the growing number of (anonymous) threats against officials constitutes a low-risk, low-cost strategy for political extremists, which can nonetheless create a significant impact on democratic processes.

This general climate of threats and violence against elected officials, which seem to be on the rise in Europe and North America, constitutes a clear danger to democracy since it appears to instill fear among officials or deter others to run for office, for example. It is the very heart of the democratic process that is affected. Furthermore, in line with the theory of “stochastic terrorism,” the growing political polarization and online verbal violence could increase the risk of political violence against elected officials by lone actors.40 n Finally, a dangerous spiraling of violence could be in the making, as a study suggests that violence against elected officials could further exacerbate support for political violence.41

Thus, in short, both the evolution of the terrorist threat landscape in Europe, and the growing levels of threats and political violence against elected officials—online and offline—suggest that terrorist and extremist attacks on political figures could rise in the future.

Conclusion

Throughout modern history, terrorist organizations have consistently targeted political leaders. This was, in their view, the most direct way to trigger change or achieve their objectives, in line with their ideology, but also the surest way to give their terrorist cause greater publicity.

Research conducted for this article identified 36 plots and attacks against European elected officials over the past 10 years, which demonstrates that the phenomenon remains a prevalent terrorist tactic. The data does not allow one to conclude that the phenomenon is rising in Europe. However, it is occurring in a broader context that could result in a growing trend of political assassinations in the future. At a minimum, it is an issue that certainly requires focus and increased vigilance. This is because certain contextual drivers—including a high but fragmented terrorist threat landscape, growing threats and violence against elected officials, as well as greater political polarization of societies and a declining trust in democratic institutions in Europe—could, as Perliger has argued, increase the risk of a resurgence of political assassinations as a terror tactic.42

Some measures could be taken to mitigate this risk. This would include, to begin with, a better monitoring of the trend in Europe and elsewhere to produce a better threat assessment. As mentioned above, existing data on the phenomenon is only fragmentary. Second, more prevention work could be done, online and offline, to raise awareness and increase resilience among elected officials against such threats and violence, taking example on existing tools available in Germany or Sweden.43 Third, better reporting and assessment mechanisms could be established. For instance, in the Netherlands, there is a special police unit specifically dedicated to such threats.44 Fourth, new laws could be adopted to further criminalize attacks against politicians. These could be modeled after legislation that has been created for this purpose in France or Germany.45 Finally, more broadly, a reflection could be initiated on concrete security measures that could be developed to strengthen the protection of elected officials and public figures, and on the means necessary to implement such measures.46 CTC

Thomas Renard, PhD, is the Director of the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), a think tank in The Hague, Netherlands. He is also the Research Committee Chair of the European Union’s Knowledge Hub on the prevention of radicalization, and a Steering Committee member of EUROPOL’s Advisory Network on terrorism and propaganda.

Author’s Note: The author is very grateful to Yael Boerma for his research assistance in collecting data, as well as to Rik Coolsaet for his constructive comments on the first draft. He also thanks CTC Sentinel’s reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

© 2026 Thomas Renard

Substantive Notes

[a] The data collection ended on October 15, 2025.

[b] The list of countries covered in the dataset therefore includes: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Republic of Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

[c] The author explicitly excluded Ukraine, where several notable incidents occurred, because they occurred in the context of war, which is significantly different from the rest of Europe.

[d] Although definitions vary, both terrorism and violent extremism share some important commonalities, namely the support or use of violence to achieve political or ideological objectives. See, for instance, Alex P. Schmid, Radicalisation, De-Radicalisation, Counter-Radicalisation: A Conceptual Discussion and Literature Review (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2013).

[e] The queries used the following combinations of key words: Country + politician + (foiled) terrorist plot / (foiled) terrorist attack; Country + politician / president / prime minister / minister / lawmaker / mayor + (foiled) terrorist plot / (foiled) terrorist attack.

[f] The snowball search method is a way of tracking down new cases or sources, by going through the texts and references of previously identified articles.

[g] As stated above, terrorist incidents in this dataset are strictly limited to those attacks that resulted in a conviction for terrorism offenses.

[h] As stated above, the plot against the Belgian prime minister is still under investigation and could possibly result in terrorism convictions, hence adding one more case of terrorism in the period 2020-2025 (currently coded as ‘violent extremism’).

[i] Some examples in the dataset include the murders of Labour Member of Parliament Jo Cox in the United Kingdom in 2016 and local conservative official Walter Lübcke in Germany in 2019. Both officials were killed by far-right extremists.

[j] Some examples in the dataset include the assault on a German left-wing politician during the 2024 elections campaign; the firebombing of two Greek parliamentarians’ private houses in the context of a highly sensitive vote on the political agreement between Greece and the Republic of North Macedonia in 2019; and the murder of Jo Cox in the United Kingdom in the context of the so-called Brexit vote.

[k] In addition to its federal parliament, which is one of the largest in Europe, Germany counts 16 regional parliaments and many local councils.

[l] For instance, Mauro Lubrano explains how anti-technology extremists, notably on the far-left, consider the “techno-elite” and its enablers (including government) the enemy. See Mauro Lubrano, Stop the Machines: The Rise of Anti-Technology Extremism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2025).

[m] There are a number of significant exceptions, of course, as illustrated by the very lethal terrorist attacks perpetrated by Timothy McVeigh, Anders Breivik, or Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel (perpetrator of the 2016 Nice attack).

[n] Stochastic terrorism is a recent theory according to which the proliferation of violent language, particularly online, would increase the risk of physical violence.

Citations

[1] Jessica Rawnsley, “Suspected jihadist drone plot against Belgian PM foiled,” BBC, October 10, 2025.

[2] “Vance Boelter Indicted for the Murders of Melissa and Mark Hortman, the Shootings of John and Yvette Hoffman, and the Attempted Shooting of Hope Hoffman,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, District of Minnesota, July 15, 2025.

[3] Jan Lopatka, “Slovak PM Fico’s attacker convicted of terrorism, jailed for 21 years,” Reuters, October 21, 2025.

[4] Shivani Chaudhari, “Sir David Amess killer ‘left Prevent too quickly,’” BBC, February 12, 2025.

[5] “Walter Lübcke: Right-wing extremist Stephan Ernst handed life sentence for murder of pro-migrant MP,” Euronews, January 28, 2021.

[6] Sarah Marsh, “Isis terrorist jailed for life for plot to kill Theresa May,” Guardian, August 31, 2018.

[7] Robert A. Pape, “America’s New Age of Political Violence,” Foreign Affairs, October 9, 2025; Pete Simi, Gina Ligon, Seamus Hughes, and Natalie Standridge, “Rising Threats to Public Officials: A Review of 10 Years of Federal Data,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024).

[8] Charles Townsend, “The reign of terror” in Charles Townsend, Terrorism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford Academic, 2018).

[9] Richard Bach Jensen, The Battle Against Anarchist Terrorism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[10] “France: Objective: De Gaulle,” Time, October 8, 1973.

[11] John Foot, The Red Brigades: The Terrorists who Brought Italy to its Knees (London: Bloomsbury, 2025).

[12] José A. Olmeda, “ETA Before and After the Carrero Assassination,” Strategic Insights 10:2 (2011).

[13] Rory Carroll, Killing Thatcher: The IRA, the Manhunt and the Long War on the Crown (London: HarperCollins, 2023).

[14] Arie Perliger, The Rationale of Political Assassinations (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2015).

[15] See, for instance, Wesley S. McCann, “Who Said We Were Terrorists? Issues with Terrorism Data and Inclusion Criteria,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 46 (2023); Stephen Johnson and Gary A. Ackerman, “Chapter 11: Terrorism databases: problems and solutions” in Lara Frumkin, John Morrison, and Andrew Silke eds., A Research Agenda for Terrorism Studies (Cheltenham, England: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023).

[16] Alex P. Schmid, Defining Terrorism (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2023).

[17] Ionel Zamfir, “Violence and intimidation against politicians in the EU,” European Parliamentary Research Service, October 2025.

[18] Thomas Hegghammer and Neil Ketchley, “Plots, Attacks, and the Measurement of Terrorism,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 69:1 (2023).

[19] Simi, Ligon, Hughes, and Standridge.

[20] Tore Bjørgo, Anders Ravik Jupskås, Gunnar Thomassen, and Jon Strype, “Patterns and Consequences of Threats Towards Politicians: Results from Surveys of National and Local Politicians in Norway,” Perspectives on Terrorism 16:6 (2022); Pape.

[21] Damien McGuinness, “Germany unveils measures to tackle far-right surge,” BBC, February 13, 2024.

[22] Lamprini Rori, Vasiliki Georgiadou, and Costas Roumanias, “Political violence in Greece through the PVGR database: evidence from the far right and the far left,” Paper No. 167, Hellenic Observatory Discussion Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe, January 2022.

[23] Joshua Molloy, “13 Years On: The Enduring Influence of Breivik’s Manifesto on Far-Right Terror,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, July 24, 2024.

[24] “Police investigate threats made to elected representatives,” BBC, December 2, 2025.

[25] Laura Winkelmuller Real, Kacper Rekawek, and Thomas Renard, In Their Eyes: How European Security Services Look at Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2025).

[26] Ibid.

[27] Petter Nesser, Islamist Terrorism in Europe: A History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[28] Perliger.

[29] Zamfir.

[30] Owen Scott, “More young adults today believe political violence can be justified: poll,” Independent, September 25, 2025.

[31] “Political violence is becoming more and more acceptable in Europe, study shows,” NL Times, July 20, 2024.

[32] Agata Kalabunowska, “Politically Motivated Extreme-Right Attacks Against Elected Representatives in Contemporary Germany,” Perspectives on Terrorism 16:6 (2022).

[33] “Loi du 21 mars 2024 renforçant la sécurité et la protection des maires et des élus locaux,” Vie Publique, March 22, 2024.

[34] Jaap Bouwmeester and Charlotte van Miltenburg, “Trend toenemende agressie en intimidatie tegen decentrale politici niet gekeerd,” Ipsos, December 17, 2024.

[35] Maxime Daye, “Colloque ‘Le Blues des Élus’ Resultats de l’Enquete de l’UVCW Realisee par Dedicated,” Mouvement Communal, September 2023.

[36] “En 2024, 101 personnes ont bénéficié d’une protection suite à des menaces dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions,” Centre de crise National, January 9, 2025.

[37] Bjørgo, Jupskås, Thomassen, and Strype.

[38] Robert A. Pape, “Rising Threats to Members of Congress: New CPOST Study Shows Threats against Members of Congress Increased Sharply in 2017, Targeting both Democrats and Republicans,” Chicago Project on Security and Threats, October 8, 2025.

[39] Simi, Ligon, Hughes, and Standridge.

[40] Fook Nederveen, Emma Zurcher, Rick Slootweg, Felicitas Hochstrasser, and Stijn Hoorens, “From words to actions: An exploration and critical review of the concept of ‘stochastic terrorism,’” Rand Europe, 2024.

[41] Alessandro Nai, Patrick F.A. van Erkel, and Linda Bos, “Violence Against Politicians Drives Support for Political Violence Among (Some) Voters: Evidence from a Natural Experiment,” Public Opinion Quarterly 89:2 (2025).

[42] Perliger.

[43] “Your rights,” Stark im Amt, n.d.; “Trygghet för förtroendevalda – stöd, metoder och kunskap för att motverka hot och hat,” Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner, August 21, 2025.

[44] “Politici moeten hun werk ongehinderd kunnen doen,” Openbaar Ministerie, n.d.

[45] Zamfir.

[46] See Kacper Rekawek, Surveillance and Protection-Insights from the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia (The Hague: International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, 2025) and Edwin Bakker and Marieke Vos, “Reflectie op Bewaken en Beveiligen,” Netherlands Police Academy, March 12, 2023.

Skip to content

Skip to content