Abstract: This article examines how European criminal justice systems prosecute minors and young adults involved in terrorist-related activities. Using a dataset of 98 cases from Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom (2020 to mid-2025), it analyzes legal frameworks and sentencing practices for juvenile extremist offenders (JEOs) aged 10 to 23 years. Nearly 30 percent of terrorism arrests in E.U. states in 2024 involved youths aged 12 to 20, primarily linked to jihadism with growing right-wing extremism cases. Most JEOs are convicted of preparatory offenses or possession and dissemination of extremist material rather than violent acts. The three examined countries employ different approaches: The United Kingdom sets the minimum age of criminal responsibility at 10 years; Germany at 14; the Netherlands at 12. Germany and the Netherlands extend juvenile justice provisions to young adults up to 21 and 23, respectively. While procedural safeguards exist, application varies significantly. Most JEOs receive custodial sentences (69 percent), often with probation and deradicalization requirements. Courts consider age, mental health, and rehabilitation efforts as mitigating factors. Additionally, this article underlines the importance of adopting a more flexible approach in the application of juvenile justice to young adults in practice and emphasizes the need for enhanced procedural safeguards when prosecuting alleged juvenile terrorists as ultima ratio.

Ever since the critically acclaimed Netflix miniseries “Adolescence” aired in March 2025, media coverage about (online) radicalization of minors and youth involved in terrorism and violent extremism has increased significantly, though authorities had already been expressing concerns about the number of especially young minors engaged in terrorist-related activities both online and offline. Indeed, the number of youths involved in terrorist and violent extremist activities had grown across the European Union in 2024.1 Nearly 30 percent of all individuals arrested on terrorism suspicion in E.U. member states in that year were aged between 12 and 20 years. While the vast majority of these cases are related to jihadism, a growing number of minors are involved in right-wing extremism or other criminal networks with links to extremism such as the 764 network.a The number of teenagers that are being arrested in the United Kingdom is also rising, in particular in relation to offenses regarding online activities such as the possession and dissemination of terrorist material.2

While many youths engaged in extremist- and terrorist-related activities are channeled through prevention programs, data shows that a considerable portion of youth still end up in the criminal justice system. Hence, in addition to exploring operational and demographic aspects such as online radicalization pathways of youths,3 and the profiles of minors in extremist plots and attacks,4 it is crucial to understand how minors and young adults can be treated by the criminal justice system in a way that serves both the interests of counterterrorism as well as the interests of the accused youngsters.

This article first provides an overview of how different jurisdictions in Europe hold minors and young adults accountable for terrorist-related conduct. It does so by providing an overview of the applicable legal frameworks in three countries with different legal traditions that are all facing increasing numbers of young extremist and terrorist offenders, specifically Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom.5 A dataset compiling domestic jurisprudence on incidents involving alleged perpetrators between the age of 10 and 23 years who were tried between January 2020 and June 2025 illustrates the practical application of these frameworks. These observations from practice shed light on the type of terrorist conduct that youths and young adults are charged with, sentences imposed on them, and the role that age and other personal circumstances play in sentencing. Based on these findings, this article concludes by outlining some research gaps and shares observations and trends for how to hold alleged young extremist offenders criminally accountable.

The Dataset

The following analysis is informed by a dataset of criminal cases from Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom involving individuals with alleged extremist background aged between 10 and 23 years of age. The dataset is compiled of relevant cases involving terrorist-related charges in which a first instance verdict was reached between January 2020 and June 2025. Relevant cases were identified based on previous case-law related research by the authors as well as by searching domestic jurisprudence databases and press releases from relevant authorities. In doing so, the authors used standardized search terms in Dutch, English, and German relating to young age, juvenile justice, and different ideologies. This list of cases was checked against case-law overviews in existing research.b Finally, online searches using the names of already identified defendants, courts, and key terminology in all of the above-mentioned languages corroborated the collected information.

The dataset compiling 98 cases (29 from Germany, 16 from the Netherlands, and 53 from the United Kingdom) is considered fairly comprehensive, albeit not exhaustive. Nevertheless, it allows for preliminary analyses and first insights into the prosecution of alleged young extremist offenders in different European jurisdictions.

Juvenile Justice and Youths Involved in Terrorism

For the purpose of this research, individuals aged between 10 and 23 years old who are allegedly involved in terrorist- or extremist-related crimes will be referred to as juvenile extremist offenders (JEO). This term most accurately reflects the different levels of involvement in extremism or terrorism by these youths, which is not always characterized by violent acts. In fact, only one 10- to 15-year-old across the entire dataset was convicted for violent acts. Similarly, 15 percent of the 16- to 18-year-old group, and 10 percent of the 19- to 23-year-old offenders in the dataset committed violent acts against persons or objects. Around two-thirds of all 10- to 23-year-old JEOs were convicted of non-violent acts, while 23 percent were convicted for preparing acts of terrorist violence.

Acknowledging that young people are still developing physically, psychologically, and socially is the guiding assumption behind the development of juvenile justice systems. Common criminal justice is not considered suitable for youth offenders as it does not adequately consider the rights and needs of children and does not provide sufficient procedural safeguards during criminal proceedings to protect children’s fundamental rights.6 Hence, the overall objective of juvenile justice is to take the interests of the child into account and to facilitate the reintegration of youth offenders.7 To this end, the European Union and the Council of Europe have adopted legal standards and guidelines on how to ensure that age-appropriate measures and safeguards are adopted during criminal proceedings.8

These standards are applicable to all juveniles regardless of the type of crimes they are accused of and thus also to JEOs. The Global Counter-Terrorism Forum (GCTF), consisting of 32 members including Germany, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, adopted the non-binding Neuchâtel Memorandum on Good Practices for Juvenile Justice in a Counterterrorism Context to address the needs of children engaged in terrorist-related activity specifically.9 However, children in the context of terrorism and violent extremism could often be considered victims themselves as they may have been exploited by terrorist groups or extremist groups, which further complicates determining their culpability.10 Furthermore, due to the nature of counterterrorism legislation, alleged JEOs can be subjected to special investigative powers and specific procedures under counterterrorism laws, for example longer pre-trial detention. Additionally, alleged JEOs may specifically be impacted by the collection and sharing of data and watchlisting.11

Against this background, the principle of ultima ratio—meaning that criminal justice should only be invoked as a last resort due to its coercive nature—is of particular significance for JEOs.c When minors have not committed serious offenses and do not pose an imminent threat to others or society at large—as suggested by the data analyzed for this article and outlined below—one might consider prioritizing diversionary and increased preventive measures over criminal prosecution.

Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility

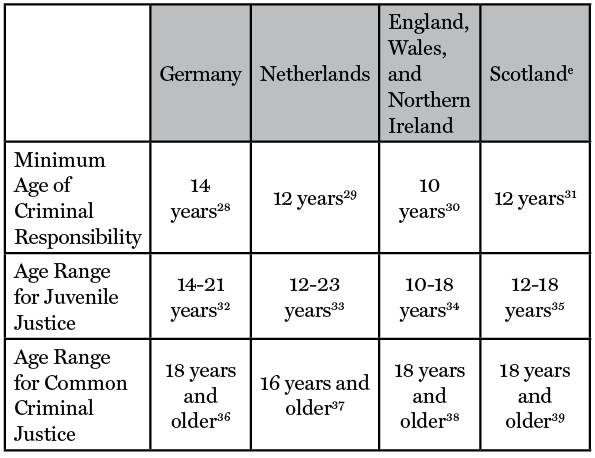

Although, based on scientific findings, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) recommends states set the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) at 14 years regardless of the type of offense,12 this varies significantly across national jurisdictions and is often set far below the age of 14 (Table 1).13 Minors below the MACR who have allegedly committed an offense are recommended to be treated by the social welfare system.14

This approach has indeed been adopted by many states. In Germany, for example, alleged offenders below the MACR, meaning below 14 years, and their families can receive pedagogical support from child welfare services.15 Only if such a cooperation fails can family courts be ordered to intervene and under narrow conditions take restrictive measures such as placement in a closed pedagogical facilities to avoid significant risk for self-harm or harm to others.16 Similarly in the Netherlands, among other non-criminal measures, children younger than 12 years suspected of having committed an offense can still be questioned by law enforcement under special protective measures or be referred to a family court.17 Lastly, in England and Wales, one measure to support children below the age of 10 who allegedly showed otherwise criminalized conduct, is for family courts to issue a child safety order. Such an order determines individual measures to ensure the child receives adequate care and support.18

However, once a child has reached the MACR and allegedly committed a crime, it is not always clear whether they will be subjected to juvenile justice or common criminal justice. Some jurisdictions allow for the application of juvenile justice for young adults older than 18 years depending on their level of maturity and the specific circumstances of their case.19 Conversely, against the advice of international children’s rights bodies,20 some states such as the Netherlands allow underaged individuals above the age of 16 to be subjected to common criminal justice (Table 1).21

Also against the advice of international children’s rights bodies,22 some countries such as Australia have lowered the MACR for certain serious offenses.23 Similar debates about whether the MACR should be lowered also continue in other countries, including Swedend and Germany.24 Nevertheless, longitudinal studies show that the overall number of juveniles involved in crime has been declining in several European countries.25 Furthermore, a study conducted in Denmark, where the MACR has been temporarily lowered by one year, found that there is little evidence to support that the lower MACR had a deterrent effect.26 These findings suggest that lowering the MACR or creating exceptions for terrorist offenses risks undermining children’s rights without achieving significant deterrent effects. Furthermore, in line with the ultima ratio principle, subjecting juveniles and developmentally immature young adults who likely have limited exposure to the criminal justice system could bar or potentially undermine preventive interventions. Indeed, evidence from jurisdictions prioritizing early prevention over criminal prosecution suggests positive outcomes. Scotland’s ‘Getting it right for every child’ policy, which raised the MACR and put more emphasis on early intervention, significantly reduced cases reaching the youth courts while youth offending declined overall.27 This suggests that addressing root causes of youth delinquency—which is of particular importance in terrorist-related contexts where ideological exploitation may play a role—can be more effective than punitive criminal justice responses.

Table 1: Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility by Country

When a case in Germany or the Netherlands involves alleged criminal acts committed at different ages, these acts can be tried jointly in one case, requiring the competent court to determine whether to apply juvenile or common criminal justice in the joint case.40 German law explicitly proscribes that such a decision depends on whether the primary focus of the proceedings is on crimes committed at an age or level of maturity that gives rise to juvenile justice or at an age or level of maturity that gives rise to common criminal justice.41

Lastly, several countries such as the Netherlands and Germany take a more flexible approach to the application of juvenile justice by providing for age ranges (Table 1) in which it is up to the discretion of judges to determine whether to apply juvenile justice or common criminal justice. In doing so, these countries attempt to accommodate the special needs of adolescents.42 However, adolescents are defined differently in these two countries, with the age range in Germany being 18 to 21 years and 16 to 23 years in the Netherlands. These more flexible approaches to juvenile justice in Germany and the Netherlands are also reflected in the breakdown of criminal justice frameworks applied to JEOs in different age categories pursuant to the dataset. While in the United Kingdom any JEO above the age of 18 is automatically subjected to common criminal justice, 87.5 percent of the JEOs in Germany between 18 and 21 years were subjected to certain elements of juvenile justice. However, only 15 percent of the JEOs in the Netherlands between the age of 16 and 23 were subjected to certain elements of juvenile criminal justice, suggesting that the practical application of these provisions to adolescents and young adults remains limited.

Elements of Juvenile Justice

In line with the rationale of juvenile justice set out above, these frameworks do not mean that alleged offenders of a young age are automatically being held criminally accountable. Instead, juvenile justice frameworks govern means of diversion and non-criminal justice procedures. In cases in which alleged JEOs are indeed subjected to criminal proceedings, juvenile justice provides for age-specific safeguards, relating to criminal procedure, sentencing, and penalties.

Youth Courts

A common feature of juvenile justice is the use of specialized criminal courts, also referred to as youth courts, although the scope and procedures may differ between countries. In the United Kingdom, youth courts have jurisdiction to hear cases of minors aged between 10 and 17 years for less serious crimes such as theft and drug offenses. Notably, there is no jury in a youth court, and the case is adjudicated by magistrates or a judge.43 Cases involving more serious offenses, including terrorism offenses, are generally heard by a Crown Court.44 Hence, only eight JEOs who were prosecuted in the United Kingdom were confirmed to have been tried at a youth court.

The Netherlands has a more flexible, yet complex system. Minors between 12 and 15 years are always tried in youth courts. However, depending on the level of maturity, the seriousness of the crime, and the circumstances of a case, 16- and 17-year-olds can be tried either in a youth or a regular criminal court but always receive youth sentences.45 Young adults between 18 and 23 years are tried in regular criminal courts, but can be sentenced under juvenile justice depending on the personality of the accused or the circumstances under which the alleged offense was committed.46 In practice, factors that should be taken into account in determining the personality and circumstances are whether the accused is attending school, living at home with their parents, requires support in relation to cognitive limitations, or is still receptive to educational programs.47

Juvenile offenders in Germany are usually tried before a youth judge, youth jury, or youth chamber.f However, certain offenses are excluded and are always tried in a regular criminal court. So-called state protection matters, which among others include terrorist offenses and core international crimes, are tried at a Higher Regional Court on first instance regardless of the age of the accused.48 Thus, all JEOs are tried at a Higher Regional Court when they are charged with terrorist offenses. Nonetheless, additional procedural safeguards are in place.49

Additional Procedural Safeguards

To adhere to the age-specific needs of juveniles, common procedural arrangements exist—next to youth sentences—in all three countries assessed for this research. This, for example, includes the possibility of holding proceedings behind closed doors; imposing reporting restrictions on the media, such as anonymizing the defendants; allowing them to participate in a child-friendly way in criminal proceedings; involving parents in the criminal proceedings and child protection services; and limiting the duration and location of pre-trial detention. These safeguards are particularly relevant when JEOs are being tried before a regular criminal court.

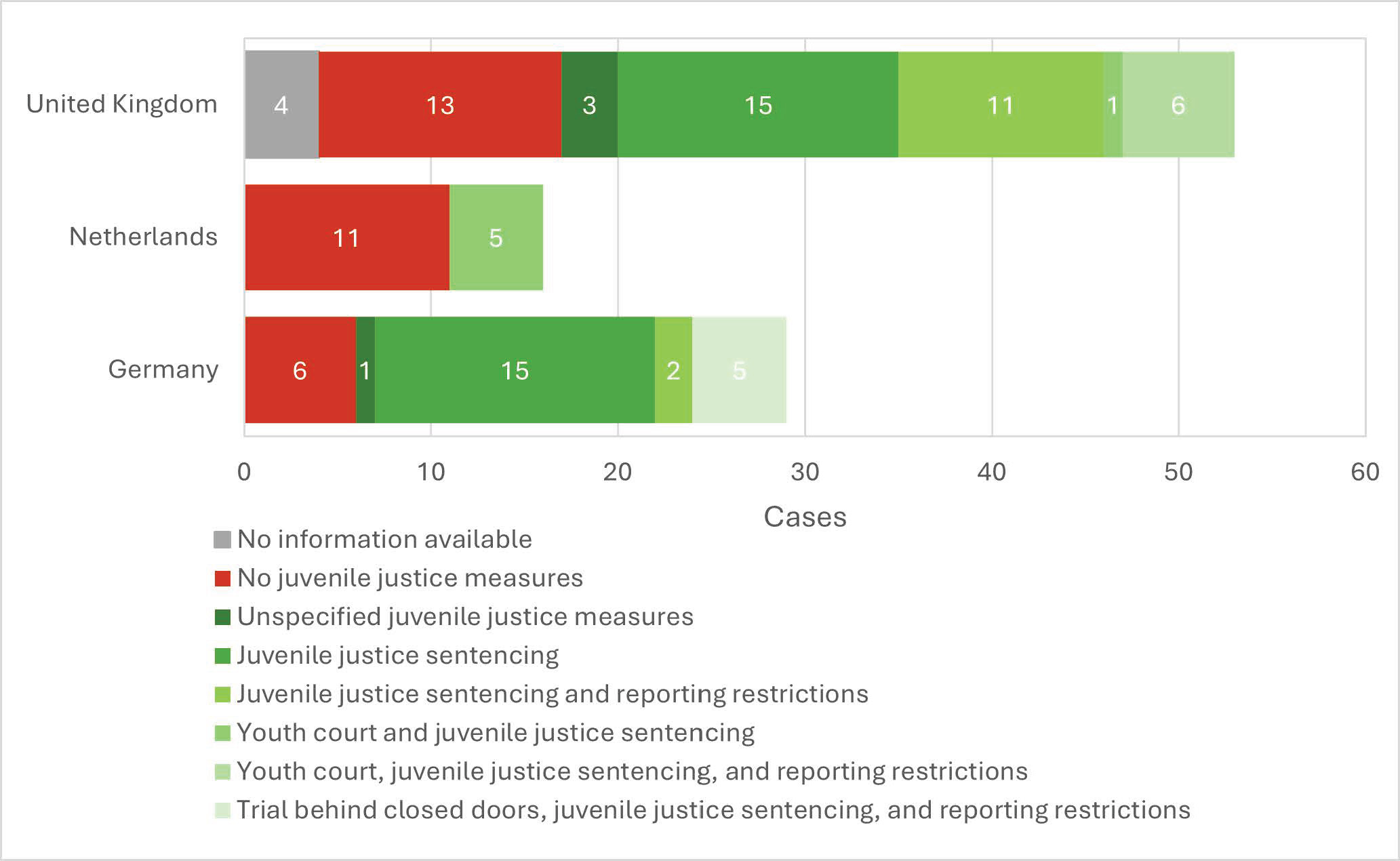

JEO Trials by Country

When prosecuting JEOs, courts in Germany and the United Kingdom most frequently order reporting restrictions, although they have been lifted after sentencing in several cases in the United Kingdom. In cases involving underage JEOs as defendants in Germany and the Netherlands, it has also been confirmed that child protection services were involved in the proceedings. Only five of 98 cases involving JEOs were held behind closed doors.g Across all three countries, however, the one juvenile justice element that is most frequently applied to JEOs, regardless of whether they are being tried at a youth court or not, is sentencing pursuant to juvenile justice frameworks.

Ideological Background, Gender, and Charges

The ideological currents of JEOs in the dataset are mainly two-fold with 53 percent jihadi JEOs and 46 percent right-wing extremist (RWX) JEOs.h Notably, the share of female JEOs (18 percent overall) solely relates to jihadism (35 percent of all jihadi JEOs). All but one woman were tried in Germany and the Netherlands and have attempted or succeeded in traveling to Syria or Iraq.i Unlike the United Kingdom, Germany and Netherlands have repatriated several women from northeast Syria in the early 2020s and subsequently prosecuted them for their involvement with terrorist organizations such as the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and Jabhat al-Nusra.50 Overall, girls and young women are mostly being convicted of supporting acts, including aiding and abetting terrorist offenses committed by male offenders or membership in a terrorist organization.j While there are no RWX girls or young women in the present dataset, this should not lead to the assumption that women are not active or engaged in right-wing extremism. In fact, research has shown that just like women involved in jihadi terrorism, women and girls involved in right-wing extremism are involved in mainly non-violent roles, propaganda, and recruitment activities, as seen, for example, with women involved in the January 6th attack.51

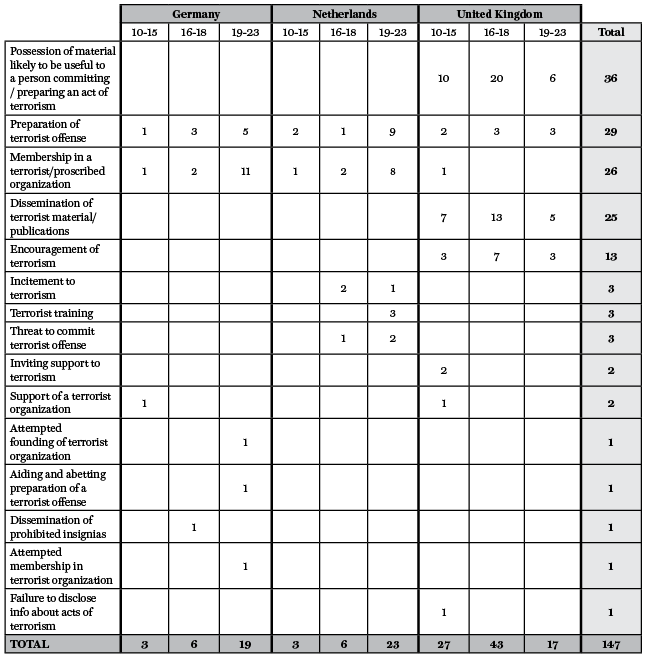

In all three countries, most JEOs are convicted for preparatory offenses or the possession and dissemination of extremist material. Only a small proportion is responsible for serious acts of violence that directly harm individual victims or society. (See Appendix A.)

Forty-two percent of the convictions of JEOs in the United Kingdom relate to, mostly digital, possession of terrorist material (sect. 58 Terrorism Act 2000) and 29 percent to dissemination of terrorist publications (sect. 2 Terrorism Act 2006), also referred to as documentary offenses. Furthermore, 15 of the convictions of JEOs in the United Kingdom relate to encouragement of terrorism (sect. 1 Terrorism Act 2006). Similarly, three JEOs in the Netherlands were convicted of incitement to terrorism (art. 47 SR) and one JEO in Germany was convicted of showing insignias of a prohibited organization (sect. 86a StGB). However, thought or speech offenses such as incitement, encouragement, and glorification of terrorism may interfere with children’s right to freedom of expression and in their process of forming their identity, which is often driven by curiosity and being susceptible to peer pressure and provocation.52 Furthermore, criminality related to the mere possession of material that can likely be used for terrorist activities can disproportionally affect minors who may be simply thoughtless or curious rather than intending to participate or support acts of terrorism. This is because terrorist intention of the person possessing such material does not need to be proven under U.K. law and can thus also capture thoughtless or curious minors.k

In addition to terrorist-related offenses, several RWX JEOs in the United Kingdom are more recently also being convicted of possession of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) and coercion.l And in Germany and the Netherlands, several jihadi JEOs were also convicted for core international crimes, including genocide and crimes against humanity, committed in Syria and Iraq.53

Sentencing and Penalties

The most common element of juvenile justice in relation to JEOs across all the three countries is handing down penalties in accordance with juvenile justice standards.m The purpose of sentencing youth offenders is distinct from adults, and all three jurisdictions recognize the need to take the age and welfare of the children into account, placing a stronger focus on education, reintegration, and reducing recidivism.54

According to the UK Sentencing Council, courts can impose a variety of sentences to juvenile offenders with custodial sentences, meaning imprisonment that generally can only be imposed for the most serious crimes, being the last resort.55 Non-custodial sentences range from financial orders and community sentences with specific conditions, which are also referred to as a youth rehabilitation order, to specific intensive supervision orders or youth referral orders that can only be imposed on otherwise imprisonable offenses upon guilty plea.56 Notably, U.K. courts can also impose a parenting order for minors below the age of 17 years.57 The sentencing of JEOs under the age of 18 is also affected by the adoption of Counter-Terrorism and Sentencing Act in 2021, as it introduces a special dangerous child offenders category where the maximum sentence for the offense is life imprisonment. When applied, it introduces a mandatory period of supervision after release, and withdraws the possibility for early release.58 While JEOs older than 18 years are to be sentenced in accordance with the purposes of sentencing of adults, courts still need to take their level of maturity into consideration when determining the appropriate sentence and place them in a young offender institution.59 The U.K. government recognizes that indeed many JEOs do not pose a significant security risk to society and is therefore planning to introduce a youth diversion order that aims to prevent them from engaging further in terrorist activities at an early stage and avoid criminal prosecution.n

In the Netherlands, juveniles and young adults between the ages of 16 and 23 can be tried either pursuant to adult criminal law or juvenile justice. Notably, procedural safeguards are not altered and thus juveniles until the age of 18 are tried in juvenile courts but adult sentences can be imposed, whereas young adults between 18 and 23 years old are tried in regular courts but youth sentences can be imposed.60 Youth sentences can include a custodial sentence; community service, which can be a combination of labor and educational measures; or financial fines. For juveniles younger than 16 years, the maximum permitted period of detention is one year. For those aged above but sentenced according to juvenile justice, the maximum prison term is two years.61 A recent study revealed that juveniles between 16 and 17 years who are sentenced under adult criminal law receive longer sentences, often have a criminal record, and are less likely to be receptive for educational interventions compared to their peers sentenced pursuant to juvenile criminal law.62 The present dataset only includes two minors in the Netherlands aged 16 or 17 who have received youth sentences, thus making it impossible to draw any comparable observations for JEOs in particular.

In Germany, juveniles are sentenced according to juvenile justice standards regardless of whether they are being tried in a youth court or in a regular criminal court.63 This can also be applicable to young adults between 18 and 21 years as detailed above. While this sentencing can entail certain special sentences such as educational or disciplinary measures, custodial sentences are handed down in more serious cases.64 The length of custodial youth sentences usually ranges from six months to five years.65 However, for offenses in which common criminal justice provides for a custodial sentence of more than 10 years, the maximum custodial sentence under juvenile justice is 10 years. To provide for more discretion and enhance educational and rehabilitative efforts, fixed sentencing ranges, as prescribed for specific offenses under common criminal justice, are not applicable in juvenile justice proceedings.o

Since German and Dutch courts have discretion on whether to sentence young adults of a certain age range pursuant to juvenile or adult justice, courts in both countries regularly consider the individual personal circumstances of the JEO and whether the convict would benefit from the educational focus of juvenile sentencing. In doing so, they rely on expert advice from youth services, as provided by law.

However, not all JEOs tried in Germany and the Netherlands were still below the age of 21 or 23 years, respectively, at the time of trial. In these cases, courts provided more elaborate reasons on why they applied juvenile justice sentencing or not, where they had discretion to do so. In the case of Monika K., a German court found that even though the defendant was above the age of 21 years for most of her time with the Islamic State, the charges predominately related to actions and personal circumstances when she was younger than 21 years with a limited maturity. Furthermore, the court concluded that although she was 28 years old at sentencing, she could still benefit from educational measures under juvenile justice given her efforts to mature further.66 Hence, the court sentenced her according to juvenile justice frameworks. Conversely, in the case of Ilham B., who was between 19 and 23 years old while being a member of Jabhat al-Nusra and the Islamic State and also 28 years old at the time of trial on first instance, a Dutch court found that the educational measures under juvenile justice were no longer suitable since she had already matured, was a mother of two children, and lived separately from her parents.67

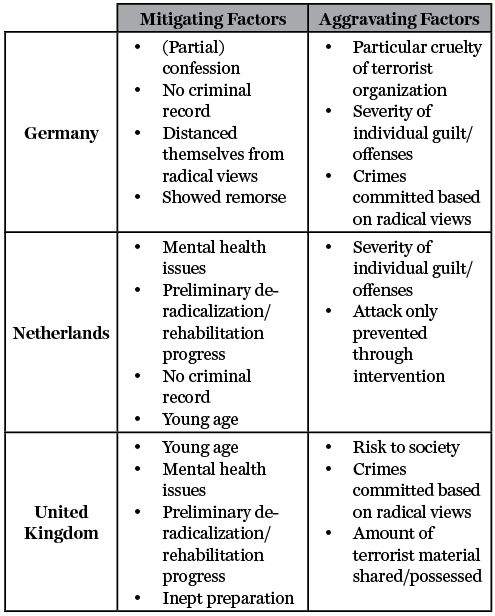

Even when JEOs were sentenced pursuant to adult criminal justice, their young age at the time of commission of the crimes was often taken into consideration as a mitigating factor in all three countries (38 percent of respective cases in which sentencing considerations are known). Overall, judges in all three countries took similar mitigating and aggravating factors into account when sentencing JEOs pursuant to juvenile justice (Table 2). Although not among the most common mitigating factors, courts in all three countries had several cases in which they had to consider undue delays in proceedings as a mitigating factor.

Table 2: Most Common Mitigating and Aggravating Factors for JEOs Sentenced Pursuant to Juvenile Justice in Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom

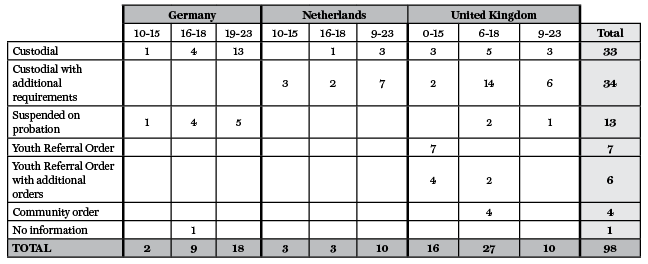

Ultimately, the vast majority (69 percent) of the JEOs received custodial sentences (Appendix B). In half of these cases, custodial sentences were combined with additional measures such as probation periods. These probation periods often involved special conditions, including but not limited to monitoring of online activities, participation in deradicalization programs, and reporting duties. In the United Kingdom, 13 JEOs sentenced pursuant to juvenile justice received a youth referral order.68 In determining whether to impose a custodial sentence on underaged JEOs or not, sentencing judges in the United Kingdom often considered in favor of the defendant when they made first successful steps to deradicalize during the proceedings.p

Lastly, 13 JEOs in the United Kingdom also received a terrorism notification requirement, meaning they must regularly report correct up-to-date personal information to the authorities.69 This requirement has been imposed on JEOs as young as 16 years at the time of sentencing for between 10- and 30-years duration. The duration and continued burden of this requirement conflicts with the educational and rehabilitative focus of juvenile justice.

However, it is not only the long-term reporting duties that can have an adverse impact on the rehabilitation of young terrorist offenders. A terrorism conviction itself can have negative implications when applying for employment, educational opportunities, or insurance. These effects might persist well into adulthood, raising questions about proportionality, particularly given that the majority of JEOs in this dataset were convicted of preparatory or speech-related offenses rather than violent acts causing direct harm to individuals or society.

Conclusion

Tracking cases of juveniles and young adults involved in terrorist conduct remains a challenge. Many minors fall below the age of criminal responsibility, are subject to administrative measures, or are merely reprimanded by police, making it difficult to establish precise figures. What is clear, however, is that the number of juveniles and young adults engaged in terrorist-related activities in Europe is rising. In particular, the number of arrests of minors linked to the 764 network and other off-shoots of the Com network is increasing;70 however, many of these fell outside the temporal scope of the dataset used for this research and are thus not included in the data. Media reporting—particularly since the airing of “Adolescence”—has amplified the image of the “teenage terrorist,” yet data suggests a more nuanced reality.

Findings from Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom reveal several important considerations for policy and practice. First, the data shows that the number of JEOs linked to jihadism and prosecuted in these three countries between 2020 and mid-2025 is only slightly higher than of those linked to right-wing extremism, confirming that jihadi and right-wing extremist groups both exploit youth for their purposes. Second, prosecuting JEOs is resource-intensive, and the profound long-term consequences of criminal convictions raise questions about proportionality, particularly given that most JEOs are convicted of preparatory or documentary offenses rather than violent acts causing direct harm.

Recognizing that brain development continues into early adulthood71 necessitates a flexible approach and the extension of juvenile justice provisions to young adults. This not only includes procedural safeguards to protect JEOs from disproportionate counterterrorism powers such as prolonged pre-trial detention and watchlisting, but also sentencing practices that are tailored to individual maturity, seriousness of the offense, and receptiveness to educational programs.

Finally, the absence of prosecutions involving young women in right-wing extremism cases, despite documented involvement in these movements, points to gaps in understanding gendered patterns of extremist engagement that require further research to inform comprehensive responses. CTC

Tanya Mehra, LLM is a Senior Research Fellow and Programme Lead (Rule of Law Responses to Terrorism) at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), The Hague. With a background in international law, her research focuses on rule of law approaches in countering terrorism, including criminal justice and administrative measures.

Merlina Herbach, LLM is an Associate Fellow with the Rule of Law Responses to Terrorism Programme at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT), The Hague. With a background in international law and political science, her research focuses on human rights compliant approaches to terrorism and extremism, with a particular focus on criminal justice measures and gender justice.

© 2026 Tanya Mehra, Merlina Herbach

Appendix A: Most Common Convictions per Age Range by Country

Appendix B: Type of Sentence per Age Range by Country

Substantive Notes

[a] The 764 network emerged from the Com network and is a constantly evolving ecosystem of splinter groups and offshoots. It operates at the intersection of violent extremism, child sexual abuse, and extreme violence, specifically targeting vulnerable youth online. See Marc-André Argentino, Barrett G, and M.B. Tyler, “764: The Intersection of Terrorism, Violent Extremism, and Child Sexual Exploitation,” GNET, January 19, 2024.

[b] Notably, researchers at the University of Southampton track JEOs in the United Kingdom through their Childhood Innocence Project. The July dataset of that project was also used to complement the preliminary dataset for this research. See “Research project: Childhood Innocence Project,” University of Southampton, n.d.

[c] The principle of ultima ratio is also particularly relevant to juveniles with regard to criminal investigations and sentencing. The use of investigative powers, pre-trial detention, and imprisonment should only be applied when strictly necessary, proportionate, and serving a legitimate aim. Piet Hein van Kempen, “Criminal Justice and the Ultima Ratio Principle: Need for Limitation, Exploration and Consideration” in P.H.P.H.M.C. van Kempen and M. Jendly eds., Overuse in the criminal justice system. On criminalization, prosecution and imprisonment (Cambridge: Intersentia, 2019).

[d] Pursuant to the Swedish Criminal Code, children below the age of 15 years cannot be sentenced. However, in exceptional cases they can stand trial to determine their guilt. In April 2025, a 14-year-old teenager affiliated with the 764 network was found guilty of attempted murder by a Swedish court, but was not sentenced. The Swedish government has drafted a proposal to lower the age of criminal responsibility from 15 to 13 years in the hope to address the involvement of youngsters in gang violence. See Charles Szumski, “Sweden to lower age of criminal responsibility to 13 amid gang violence crisis,” Euractiv, October 27, 2025.

[e] Since the majority of cases concerning JEOs in the dataset were tried by courts in England and Wales and due to the significant differences between the criminal justice system in Scotland and that in England and Wales, this article will only elaborate on criminal procedure in England and Wales.

[f] The expected penalty, significance of the case, and involvement of underaged victims are factors determining which type of youth court has jurisdiction over a specific case in Germany. See Sects 33-41 JGG.

[g] All five cases that were held behind closed doors involved JEOs between 16 and 21 years tried in Germany.

[h] In one case, the ideological current of the 15-year-old defendant in the United Kingdom could not be established from the media coverage without further information from the competent court or investigation authorities.

[i] In December 2024, a 17-year-old girl was convicted in the United Kingdom for possession of a document for terrorist purposes under Sect. 50 of the Terrorism Act 2000. See “Sentencing Remarks,” Recorder of London, Rex v. Timaeva, March 7, 2025.

[j] This finding was also confirmed with regard to jihadi women in previous research on women prosecuted in different European countries for their involvement with the Islamic State and other jihadi organizations. See Tanya Mehra, Thomas Renard, and Merlina Herbach, “Managing Female Violent Extremist Offenders in Europe: A Data-driven Comparative Analysis” in Tanya Mehra, Thomas Renard, and Merlina Herbach eds., Female Jihadis Facing Justice: Comparing Approaches in Europe (The Hague: ICCT Press, 2024), pp. 131-139.

[k] While a minor might fulfill all elements of the crime, prosecutors do have the discretion to decide whether prosecution is suitable. Factors that are taken into account include whether there is a link with terrorist activities or a terrorist mindset and whether a criminal justice approach is suitable.

[l] First, such cases are now also being prosecuted in Germany, as shown by the arrest of a 20-year-old in June 2025. He is suspected to have committed more than 120 offenses relating to sexual abuse of minors, murder committed through a third person, and instigation to suicide of minors between 2021 and 2023. See “‘White Tiger’: Neue Details zu 20-jährigem Hamburger Mordverdächtigen,” NDR, June 19, 2025.

[m] This is applicable to both JEOs that are still underaged at the time of trial but also to adult defendants who committed crimes as juveniles, in accordance with Article 7(1)s.2 European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

[n] Although the current proposal for the youth diversion order shows similarities to the existing Prevent program, the order would entail certain restrictive measures. “Crime and Policing Bill” doc no. HL Bill 111, UK Parliament, June 19, 2025, part 14, chapter 1.

[o] Similarly, the threshold for pre-trial detention of juveniles is higher than for adults, providing that other preliminary and educational measure should be considered first and that the proceedings should be conducted in a particularly timely manner in case the juvenile suspect is placed in pre-trial detention (Sect. 72 JGG).

[p] Such considerations, including assessment of pre-sentence reports, which among others contain information on preliminary de-radicalization efforts, as well as the level of harm that was or was likely to be caused and the risk to society posed by the offender must be made when deciding whether or not to impose a custodial sentence as last resort (sect. 6.44 sentencing children and young people guideline).

Citations

[1] “TESAT 2025 Report,” Europol, June 2025.

[2] “Crime and Policing Bill: counter-terrorism and national security factsheet,” U.K. Ministry of Justice, Policy Paper, July 21, 2025.

[3] Nicolas Stockhammer, “From TikTok to Terrorism? The Online Radicalization of European Lone Attackers since October 7, 2023,” CTC Sentinel 18:7 (2025).

[4] Eric Hacker, “Generation Jihad: The Profile and Modus Operandi of Minors Involved in Recent Islamist Terror Plots in Europe,” CTC Sentinel 18:6 (2025).

[5] “Extremismus wird immer jünger und immer gewalttätiger‘ – Thüringer Verfassungsschutzbericht 2024 vorgestellt,” Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk, September 15, 2025; “Dreigingsbeeld Terrorisme Nederland Juni 2025” Report, Nationaal Coördinator Terrorismebestrijding en Veiligheid (NCTV), June 2025; Jonathan Hall, KC, “The Terrorism Acts in 2023: report of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation,” Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation, July 15, 2025.

[6] Art. 40 (1) Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), UNTS 1,577:2,7531 (1990).

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Directive (EU) 2016/800 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 May 2016 on procedural safeguards for children who are suspects or accused persons in criminal proceedings,” OJ L 132, European Parliament, May 21, 2016; “Guidelines of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on child-friendly justice,” Council of Europe, November 17, 2020.

[9] “Neuchâtel Memorandum on Good Practices for Juvenile Justice in a Counterterrorism Context,” Global Counterterrorism Forum (GCTF), 2016.

[10] For more information on how to deal with children recruited and exploited by terrorist groups, see “Handbook on Children Recruited and Exploited by Terrorist and Violent Extremist Groups: The Role of the Justice System,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2017.

[11] Daniela Baro, “Collecting Children’s Personal Data for Counterterrorism Purposes: In Children’s Best Interests? Children with Alleged, Past, or Family Links to Armed Groups,” Discussion Paper, Human Rights Centre University of Essex, May 2025.

[12] “General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system,” CRC/C/GC/24, United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), September 18, 2019, para. 22.

[13] Ibid., paras 9-11.

[14] “Systematic Responses to Children under the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility who have been (Allegedly) Involved in Offending Behaviour in Europe and Central Asia,” Guidance Note, UNICEF, December 2022, p. 6.

[15] Sects 27-35 Sozialgesetzbuch – Achtes Buch (SGB VIII).

[16] Sects 1631b, 1666 Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB).

[17] “Factsheet Aanpak twaalfmin,” Ministerie Veiligheid en Justitie, February 2012.

[18] Section 11 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 as amended by section 61 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013.

[19] “General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system,” para. 32; Sect. 105 (1) Jugendgerichtgesetz (JGG); Art. 77c (1) Wetboek van Strafrecht (Sr).

[20] “General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system,” para. 30.

[21] Art. 77b (1) Sr.

[22] “General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system,” para. 25.

[23] “Justice (Age of Criminal Responsibility) Legislation Amendment Act 2023, A2023-45,” Australian Capital Territory, November 15, 2022, sect. 70.

[24] Elisabeth Hoffmann, “Früher Schuldfähig? Die Herabsetzung des Strafmündigkeitsalters aus Sicht der Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie,” Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS), June 26, 2025.

[25] Lesley McAra and Susan McVie, “Transformations in youth crime and justice,” in Barry Goldson ed., Juvenile Justice in Europe: Past, Present and Future (New York: Routledge), pp. 74-103.

[26] Aann Piil Damm, Briit Østergaard Larsen, Helena Skyt Nielsen, and Marianne Simonsen, “Lowering the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: Consequences for Juvenile Crime,” Journal of Quantitative Criminology 41 (2025): pp. 495-521.

[27] Lesley McAra and Susan McVie, “Raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility: lessons from the Scottish experience,” Current Issues in Criminal Justice 36:4 (2023): pp. 386-407.

[28] Sect. 1 (2) JGG.

[29] Art. 77a Sr; Art. 486 Wetboek van Strafvordering (Sv).

[30] Section 50 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1933 as amended by section 16(1) of the Children and Young Persons Act 1963; Section 3 of The Criminal Justice (Children) (Northern Ireland) Order 1998.

[31] Section 41 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 as amended by section 1 of the Age of Criminal Responsibility (Scotland) Act 2019.

[32] Sects 1 (2), 105 JGG.

[33] Arts 77b, 77c and c Sr.

[34] Sect. 117 (1) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

[35] Section 307 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 as amended by section 199 of the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011.

[36] Sect. 1 (1),(2) JGG.

[37] Arts 77b, 77c and c Sr.

[38] Sect. 117 (1) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998.

[39] Section 307 of the Criminal Procedure (Scotland) Act 1995 as amended by section 199 of the Children’s Hearings (Scotland) Act 2011.

[40] Art. 495 (4), (5) Sv; Sect. 32 JGG.

[41] Sect. 32 JGG.

[42] Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, “Wijziging van het Wetboek van Strafrecht, het Wetboek van Strafvordering en enige andere wetten in verband met de invoering van een adolescentenstrafrecht,” 33 498 nr. 3, December 13, 2012.

[43] “Youth Courts,” U.K. Government, last accessed September 25, 2025.

[44] Section 2.3 of the Sentencing children and young people guideline. See “Sentencing children and young people guideline,” Sentencing Council, June 1, 2017.

[45] Art. 77b Sr.

[46] Art. 77c Sr.

[47] Sect. 1d. of Richtlijn en kader voor strafvordering jeugd en adolescenten, inclusief strafmaten Halt, February 1, 2021.

[48] Sect. 102 JGG.

[49] Sect. 104 JGG.

[50] Sofia Koller, “The German Approach to Female Violent Extremist Offenders” in Tanya Mehra, Thomas Renard, and Merlina Herbach eds., Female Jihadis Facing Justice: Comparing Approaches in Europe (The Hague: ICCT Press, 2024), p. 63; Tanya Mehra, “The Dutch Approach to Female Violent Extremist Offenders” in Tanya Mehra, Thomas Renard, and Merlina Herbach eds., Female Jihadis Facing Justice: Comparing Approaches in Europe (The Hague: ICCT Press, 2024), p. 95.

[51] Devorah Margolin and Hilary Matfess, “The Women of January 6th: A Gendered Analysis of the 21st Century American Far-Right,” Program on Extremism, George Washington University, February 4, 2022.

[52] “Protecting Children’s Rights and Keeping Society Safe: How to Strengthen Justice Systems for Children in Europe in the Counter-Terrorism Context?” International Juvenile Justice Observatory Report, October 2018, p. 28.

[53] For further analysis of so-called cumulative charging, see Tanya Mehra, “Doubling Down on Accountability in Europe: Prosecuting ‘Terrorists’ for Core International Crimes and Terrorist Offences Committed in the Context of the Conflict in Syria and Iraq,” Perspectives on Terrorism 7:4 (2023): pp. 69-104.

[54] Sect. 1.1, “Sentencing children and young people guideline;” Sect. 2 (1) JGG.

[55] Sect. 1.3, “Sentencing children and young persons guideline.”

[56] Sects 6.10-6.40, “Sentencing children and young persons guideline.”

[57] Sects 3.1-3.4, “Sentencing children and young persons guideline.”

[58] Sects 22-24 of the Counter-Terrorism Sentencing Act 2021.

[59] See Chapter 3 of Sentencing Act 2020 as amended by Counter-Terrorism Sentencing Act 2021.

[60] Eva Schmidt, Stephanie E. Rap, and Ton Liefaard, “Young Adults in the Justice System: The Interplay between Scientific Insights, Legal Reform and Implementation in Practice in The Netherlands,” Youth Justice 21:2 (2020): pp. 172-191.

[61] Artikel 77h en i Sr.

[62] Lise Prop, Kirti Zeijlmans, and André Van der Laan, “De toepassing van het adolescentenstrafrecht bij 16- tot 23-jarigen: Kenmerken van (strafzaken van) de doelgroep en motivering door de rechter,” Cahier 2024-5, Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Datacentrum (WODC), pp. 27-32.

[63] Sect. 104 (1) no. 1 JGG.

[64] Sect. 17 (2) JGG.

[65] Sect. 18 JGG.

[66] Higher Regional Court Düsseldorf, Monika K., case no. 6 StS 3/22, February 14, 2023, Judgment, paras 130-150.

[67] District Court Rotterdam, Ilham B., case no. 71/148283-21, June 1, 2022, Judgment.

[68] For more information on what a youth referral order can include, see Sets 6.23-6.41 of “Sentencing children and young people guideline.”

[69] Part 4 of the Counter-Terrorism Act of 2008.

[70] Tanya Mehra and Menso Hartgens, “Fury and Void: Legal Pathways to Counter 764,” International Centre for Counter Terrorism, October 29, 2025.

[71] “General comment No. 24 (2019) on children’s rights in the child justice system,” CRC/C/GC/24, United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), September 18, 2019, para. 22.

Skip to content

Skip to content