Abstract: The competition between terror movements and counterterrorism forces is an interactive and iterative game, as the actions taken by one side are designed to defeat, circumvent, or shape the activity taken by the opposing players. To better understand these interactive dynamics, it is important to evaluate how terrorism and counterterrorism have been evolving. This article first takes high-level stock of how the spread, structure, scale, and speed of terrorism have been changing in recent years and highlights key challenges and implications for counterterrorism. It then evaluates the United States’ ongoing effort to find a sustainable counterterrorism path, a journey that has been filled with challenges, benefits, dilemmas, and opportunities, and discusses how key factors have been shaping the direction, reach, and pace of change. An important takeaway from these reviews is that while the threat of international terrorism is not what it used to be, there is a lot of change occurring across the terrorism landscape. U.S. counterterrorism has also been undergoing some important shifts, and there are open questions about whether U.S. CT forces and assets will be spread further. If not managed carefully, change taking place across these two ‘systems’ could interact in ways that may disrupt CT progress.

In less than a year, the United States will mark 25 years since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The terrorism landscape today is markedly different than it was that morning, and even the elements that remain have evolved and adapted. The landscape has been impacted by various counterterrorism actions and world events that have affected states and non-state actors alike. There is perhaps no more critical time to take stock of the state of terrorism and counterterrorism and assess how the very character of both have changed.

This article proceeds in two parts. The first examines the current state of terrorism through the lens of four major categories: spread, structure, scale, and speed. While much has changed on the terrorism front over the last decade, let alone since 9/11, developments in these key domains over the past couple of years have been particularly acute. Identifying the global terrorism trends from these categories helps illuminate what might be in store in the coming years. The second part explores recent evolutions of U.S. counterterrorism and the United States’ quest to find a sustainable CT path. It concludes with a review of key findings and implications.

The State of International Terrorism Today

Terrorism in 2025 presents a complicated picture. Across multiple dimensions—geographic spread, the organizational structure and alliances of groups, the scale and diversity of terror threat actors, and the speed of radicalization and mobilization—terrorism is both persistent and in flux. While the goal of the first half of this article is to describe the current state of terrorism today from a strategic vantage point, it is important to state plainly that such an endeavor could fill many volumes. Thus, the authors endeavor not to capture completely the current universe of threats, but rather to outline the broad contours of the threat landscape, selecting specific examples that elucidate the most pertinent trends and aspects of change.

It is also important to note that while the authors have organized these trends into four broad categories—spread, structure, scale, and speed—for ease of analysis/explanation, these should not be viewed as distinct or static categories in reality. Indeed, evolutions in one category can and regularly do impact developments in another. For example, a terrorist group’s spread into a new geographic area may impact its structure over time, as seen with the development of al-Qa`ida affiliates in the Sahel. Similarly, increases in the number of FTO designations by the United States may curtail or otherwise change the geographic spread of the implicated groups. The purpose of isolating the categories is to better situate and analyze key trends in the terrorism space in a manageable manner. It is hoped that by taking these four aspects of the phenomenon in turn, the whole can be understood more clearly.

Spread: The Geographic Span of Terrorism

The story of the geographic spread of terrorism today is one of both expansion and concentration—a difficult combination to confront. While more countries (66) experienced at least one terrorist incident in 2024 than in any year since 2018,1 terrorist activity is also increasingly concentrated in a small number of countries: 86 percent of all terrorism-related deaths in 2024 occurred in just 10 countries.2 a Seven of those countries are in Africa, five in the Sahel specifically.3

Where once the global terror threat was concentrated in the Middle East and North Africa, today it is centered in the Sahel, specifically in the tri-border region between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.4 Indeed, according to the 2025 Global Terrorism Index, the Sahel accounted “for over half of all terrorism-related deaths in 2024.”5

The data shows that while countries such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, Somalia, and Nigeria have been largely steady when it comes to significant impact by terrorism over recent years, Sahelian countries (Burkina Faso, chief among them6) have experienced a steep increase.7 In 2023 and 2024, Burkina Faso was most impacted by terrorism globally.8 Simultaneously, high-fatality attacks have punctuated the terrorism landscape—from Kerman, Iran, in January 2024 (the deadliest terrorist attack in the country since 1978) to the Crocus Hall attack in Moscow in March 2024 (the country’s deadliest terrorist attack in 20 years).9 b It is notable that both strikes were perpetrated by Islamic State Khorasan (ISK). In short, while terrorist groups have found consistently favorable conditions in the Sahel to engage in terrorism, certain networks are still capable of conducting devastating attacks in countries elsewhere.

The picture in 2025 has been bleak, particularly for Africa and the threats from the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida there. Findings from ACLED reveal that “over two-thirds of the Islamic State’s global activity in the first half of 2025 was recorded in Africa.”10 Meanwhile, according to the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, militant Islamist groups linked to al-Qa`ida affiliate Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM) today “account for 83 percent of all fatalities in the Sahel.”11 These groups have found ample ungoverned or under-governed territorial space in the region to exploit, and there have been no signs of abatement this year. Not only are groups in the region maintaining (or exceeding) their attack tempo of recent years,12 they are increasingly weakening what exists of central governments there. The situation in Mali is deeply emblematic of this trend, where a crippling fuel blockade imposed by JNIM in the country since September is impacting Bamako directly and threatening the military junta in power.13 This “expansion of its strategic economic warfare,” according to some experts, is JNIM’s “most significant show of strength to date.”14 While, according to one long-term observer, JNIM alone would not be able to take over Bamako currently, it could if it formed a coalition with other opponents of the government.15 These developments only underscore that the Sahelian challenge will continue into 2026.

Meanwhile, consistent focal areas on the terrorism map persist, although some have been quieter than in years past. For example, in Afghanistan more than two dozen terrorist groups operate inside the country today.16 In 2025, however, ISK has conducted far fewer attacks than in recent years.17 It remains to be seen if this trend holds into 2026. Conversely, regions elsewhere face entrenched or resurgent threats. Syria is illustrative in this regard. According to recent Syrian Democratic Forces numbers, “Islamic State militants staged 117 attacks in northeast Syria through the end of August [2025], far outpacing the 73 attacks in all of 2024.”18 At a time when the U.S. presence there is shrinking19 and the new Syrian government is attempting to consolidate control over the country, this resurgent threat has the potential to complicate local and regional security in 2026 and beyond.

Finally, the geographic bounds of the threat landscape were expanded considerably in 2025 following the U.S. designation of several Latin American cartels and criminal organizations and four European Antifa groups as foreign terrorist organizations. These include entities based in Mexico, Venezuela, Ecuador, Haiti, Germany, Greece, and Italy.20 This widening of the geographic aperture has implications for confronting terror threats globally, especially given finite resources dedicated to counterterrorism and the uneven/constrained level of intelligence sharing between the involved countries.

It is worth remembering that while terrorist groups are often conceptualized as geographically bound, those boundaries can be expanded through attack plotting from afar and through the operational deployment of long-range systems (e.g., drones). Terrorist groups and their adherents are inherently opportunistic and seek to exploit seams and vulnerabilities. Today, there are terror groups such as ISK that engage and place emphasis on external operations, but there are also other groups that—while remaining centered in one specific area—have shown signs they may engage in more far-reaching terror operations at some point in the future. Take, for example, the 2019 case of Cholo Abdi Abdullah, a Kenyan national who at the direction of senior leaders of Somalia-based al-Qa`ida affiliate al-Shabaab sought and “obtained pilot training in the Philippines in preparation for seeking to hijack a commercial aircraft and crash it into a building in the United States.”21

In a more recent example, there is growing concern that Hamas—a group that has never conducted a successful attack outside of Israel, the West Bank, or Gaza—is developing external operations capabilities in Europe and may seek to depart from the group’s prior modus operandi.22 Additionally, the Houthis have deployed drones and missiles at longer, and impressive, distances over the past five years, even demonstrating the ability to strike Israel. The Houthis’ ability to strike from greater distances, and in turn expand the geographic area over which they can threaten and project kinetic power, is a leading-edge indicator that range may become more accessible for other terror groups in the coming years. In short, as the terrorism threat concentrates and deepens in known areas, there are signs and indicators that—at least for some groups—they may be seeking to spread terror further afield.

Structure: The Evolving Forms of International Terror

The structure of terror threats and their alliances are critical features to examine when assessing the threat landscape today. In 2025, the two most prominent salafi-jihadi groups continue to operate, to varying degrees, as an affiliate model. With its presumptive leader, Saif al-`Adl, inside Iran, al-Qa`ida has relied on a dispersed, decentralized franchise model in recent years to sustain counterterrorism efforts against it and to “weather the Islamic State storm.”23 Today, al-Qa`ida has affiliates in the Arabian Peninsula, the Horn of Africa, the Sahel, and South Asia.24 In the Sahel and Horn of Africa alone, its branches—JNIM and al-Shabaab, respectively—are powerful, well-funded, and gaining ground.25 As Colin Clarke and Clara Broekaert have noted, however, the franchise approach “has watered down what al-Qa`ida actually stands for, having a deleterious impact on group cohesion and brand identity.”26 But the ability of al-Qa`ida affiliates to remain, and to operate in pockets around the world, particularly in areas, such as the Sahel, where the United States has limited on-the-ground capability or local partnerships to stem their activities, means that continued focus is required.

Alternately, the Islamic State administered a “province” model almost since its inception.27 Today, over six years after the end of its physical caliphate, some of those affiliates still exist—Islamic State Khorasan, for one—but placed on top of the group’s constellation of wilayat is its General Directorate of Provinces, a kind of “superstructure that now oversees the provinces themselves” and provides coherence and connection within the network.28 Aaron Zelin has warned that overlooking the GDP and “viewing only one or two of [the provinces] as a threat misunderstands that the allocation of responsibility and resources within the group’s global network has spread, providing longer-term resiliency.”29 Furthermore, as noted by one analyst, the external operations threat posed by the Islamic State has become more multi-vector.30 One need only look to the attacks in Iran and Russia in 2024, recent disrupted plots in Europe,31 and two thwarted plots to assassinate the new leader of Syria32 to find evidence of the endurance of the Islamic State in 2025, and likely into the future.

A key complicating factor is that some terror networks inspire and encourage individual supporters to conduct attacks in the countries where they reside. It is well established that the Islamic State, in addition to directed and enabled external operations, has encouraged attacks by inspired supporters in their immediate locales for years.33 To wit, readers will recall that it has been less than a year since a 42-year-old American conducted a terrorist attack in New Orleans in support of the Islamic State.34 It has been less than a month since several young men were arrested in multiple states in the United States and charged for allegedly plotting an Islamic State-inspired terrorist attack in Michigan.35

A complementary issue to consider is that the overwhelming majority of terror attacks conducted in the United States are conducted not by groups, but by individuals; it is the primary threat. While some of these individuals are inspired by groups, many others are not. One study used START data to show that, in the United States, “the number of radicalized young people with no formal allegiances or ties to recognized extremist or terrorist groups has increased by 311% in the past 10 years alone as compared to the past 5 decades.”36

The rise in importance of terror threats posed by individuals and small cells—who usually operate under ‘looser’ or more amorphous forms of structure, or with no defined or discernable form of structure at all—is reflected in statements by senior U.S. government officials. For example, when characterizing ‘top terrorism threats’ from 2020-2024, the FBI Director issued some variation of the following statement during congressional testimony each year: “The greatest terrorism threat to our homeland has been posed by lone actors or small cells of individuals who typically radicalize to violence online and use easily accessible weapons to attack targets.”37

The key takeaway: The threat posed by individuals and small cells has been a persistent feature. Not only has it broadened the forms of structure that CT investigators need to consider in the United States, it has also complicated the geographic ‘spread’ of the threat and changed the dynamics of terrorism risk, highlighting how structure and spread intersect.

Tied closely to the structure of these groups themselves are the alliances they form with other groups, and even states, and how they lead to different types of adversarial convergence. This cooperation presents challenges, as it creates opportunities for terror groups to enhance or diversify their capabilities. It also blends threat vectors, obfuscates networks and sources of activities, and compounds the challenge of understanding and combating these groups. Some alliances are more opaque than others—for example, the relationship between al-Qa`ida and Iran, where senior leaders of the group have lived for decades, has been the subject of much speculation and debate over the years.38 Developments on the alliances front in 2025 have been complex and varied; it is useful to conceive of adversarial convergence as falling into two major categories: between non-state groups and between a non-state group and state. Several topical examples are outlined next.

Houthis/AQAP/Al-Shabaab: In the non-state/non-state category, one critical case is the triangular confluence that has developed between the Houthis, al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), and al-Shabaab. According to Michael Horton, as the Houthis have sought to expand supply chains and funding beyond Iran, they have increasingly turned to AQAP in Yemen, which in turn “has opened new doors for the Houthis to interact with Horn of Africa-based militant groups such as al-Shabaab.”39 The United Nations’ Panel of Experts on Yemen has called the relationship between the Houthis and AQAP an “opportunistic alliance … characterized by cooperation in security and intelligence, offering safe havens for each other’s members, reinforcing their respective strongholds and coordinating efforts,”40 a relationship it says has continued throughout 2025 in the form of operatives training, arms trafficking, and smuggling, and an agreement to “wage a war of attrition against [Yemeni] Government forces.”41 In the case of the Houthis and al-Shabaab, in exchange for weapons, training, and expanded economic opportunities for the latter, the Houthis receive support from al-Shabaab in its “disruptive piracy activity in the Gulf of Aden and Western Indian Ocean as well as from more diversified supply arteries.”42 The U.N. panel on Yemen reported last month that cooperation between the Houthis and al-Shabaab has intensified, particularly when it comes to weapons transfers and training “in the manufacture of sophisticated improvised explosive devices and drone technology.”43 Furthermore, there is even evidence that the Houthis have collaborated with Islamic State Somalia, coordinating on intelligence and procurement of drones and technical training.44 These disparate groups’ willingness to collaborate and to continue to leverage insecurity along a vital global trade route45 has injected new complexity into an already-fraught terror picture in the region.

Houthis/China: In the non-state/state category, the newer and evolving case of the Houthis and China represents a highly transactional alliance centered on pain for common opponents and gain for respective priorities. According to reporting at the beginning of the year, the Houthis have received “Chinese-made weapons for their assaults on shipping in the Red Sea in exchange for refraining from attacks upon Chinese vessels.”46 More recently, China has been reportedly “providing the Houthis with dual-use technologies such as satellite imagery and drone components,” similarly to safeguard its shipping interests in the Red Sea.47 This comes on the heels of U.S. Treasury action against Houthi leader Mohamed Ali Al-Houthi, among others, for communicating with officials from China “to ensure that Houthi militants do not strike” Chinese vessels traveling in the Red Sea.48 Furthermore, just last month, the U.S. Commerce Department announced it had added “15 Chinese companies to its restricted trade list for facilitating the purchase of American electronic components found in drones operated by Iranian proxies including Houthis and Hamas militants.”49 Regardless of Beijing’s objectives in this case—pragmatism, reciprocity, economic advantage—this covert alliance is illustrative of how state/non-state actor cooperation complicates the terror threat landscape.

Iran/Criminal Proxies: A state/non-state alliance of significant concern is the Iranian government’s increasing use of criminal proxies to conduct attacks in order to maintain plausible deniability. According to one analyst, over the past five years, Iran has conducted 157 foreign operations, of which 22 involved criminal proxies and 55 involved terrorist proxies.50 The U.S. government is endeavoring to respond to this threat: In March 2025, the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned the Sweden-based transnational criminal organization Foxtrot Network, which it says had “orchestrated an attack on the Israeli Embassy in Stockholm, Sweden, on behalf of the Government of Iran” in January 2024.51 A joint statement by the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and 11 European countries followed this summer, condemning “the growing number of state threats from Iranian intelligence services” against their countries, stating that “these services are increasingly collaborating with international criminal organizations” to target their citizens.52 From Hell’s Angels gang members in Canada53 to the Kinahan Cartel in Ireland,54 the list of criminal entities Tehran is willing to work with is growing. Furthermore, while Iranian “pragmatism” in its use of criminal intermediaries is not new, one scholar finds Iran’s “use of criminal intermediaries now reflects a more structured approach shaped by modern constraints” against it.55 In short, these alliances continue to be sought out for their “efficiency, cover, and reach.”56

Scale: The Number and Diversity of Terror Threat Actors

The scale of the terror threat today, in terms of the number and volume of attacks and diversity of threat actors, is a critical variable when considering change in the terrorism landscape. As mentioned earlier, more countries experienced a terrorist attack in 2024 (66) than in any other year since 2018, and the Sahel has borne the brunt of the deaths caused by terrorism.57 In fact, terrorism deaths in the Sahel in 2024 were 10 times higher than in 2019.58 According to the Global Terrorism Index, the Islamic State and its affiliates were the deadliest terrorist organizations in the world in 2024, responsible for 1,805 killed in 22 countries.59 That is the largest number of countries affected by Islamic State attacks since 2020.60 The major terrorist organizations operating in the world today—the Islamic State, JNIM, TTP, and al-Shabaab—caused 11 percent more deaths in 2024, operating in 30 countries.61

When data from Myanmar is excluded, there was an eight percent increase in the number of terror attacks globally from 2023 to 2024.c But the volume of terror activity varies according to place, and the data contains a mix of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ stories. For example, while Afghanistan has witnessed a general decline in the number of terror attacks since 2020, Pakistan has experienced the opposite. According to GTI data, in 2020 there were 172 terror incidents in Pakistan. In 2024, that number jumped to 1,099—a more than 500 percent increase.62 In the Sahel, since 2020 the number of terror incidents in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger has remained high but fluctuated over that same span of time. The upward rise in the number of fatalities from terror incidents in Niger and Burkina Faso from 2020 to 2024 is particularly concerning as it demonstrates that the ability for terror networks in that region to inflict harm has escalated. In Niger, for example, fatalities steadily climbed year over year: 262 fatalities were recorded in 2020, but by 2024, that number had risen to 930.63 The terror fatality numbers of Burkina Faso, which rose from 666 in 2020 to 1,532 in 2024, are similarly bleak.64

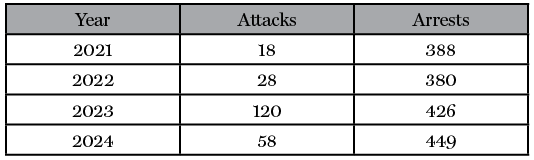

Data on terrorism-related attacks and arrests from the European Union provides another window into the issue of scale, and the trend over the last several years is sobering. Arrests increased each year—aside from a slight dip in 2022—which could be seen as a positive development that law enforcement is getting ahead of the problem but could also indicate a greater number of individuals involved in terrorist offenses who merit arrest. Meanwhile, when it comes to attacks (completed, failed, or foiled), the trend is more mixed. The overall number of attacks in 2024 was over triple the 2021 figure, over double the 2022 figure, but less than half of the 2023 figure. These high-level stats are a reminder about the ebb and flow of terrorism and how CT in the European context still requires a consistent, and potentially even growing, amount of investigatory resources.

Table 1: Terrorist attacks (completed, failed, foiled) and arrests for terrorist offenses in the European Union (2021-2024)65

Data released by the FBI and statements made by two FBI directors—Kash Patel and Christopher Wray—provide insight into threat changes and the scale of effort, including time, resources, attention, that has been required since 2019 to ‘hold the line’ and keep the number successful terror attacks in the United States low. In 2019, Director Wray shared that the Bureau had “about 5,000 terrorism cases under investigation.”66 Out of that total around 850 were focused on domestic terrorism while the rest had an international terrorism nexus, including “about 1,000 cases each of so-called homegrown violent extremism and Islamic State” and “thousands of other cases associated with foreign terrorist organizations like al-Qaida and Hezbollah.”67 During congressional testimony four years later in 2023, Director Wray noted how “the number of FBI domestic terrorism investigations has more than doubled since the spring of 2020.”68 Wray also shared that in November 2023, the FBI was “conducting approximately 2,700” domestic terrorism investigations, and in September of the same year, the Bureau was “conducting approximately 4,000” international terrorism investigations—totaling roughly 6,700 terrorism investigations.69 Nearly two years after that, in September 2025, Kash Patel noted how the Bureau was working on “1,700 domestic terrorism investigations, a large chunk of which are nihilistic violent extremism (NVE)” and “3,500 international terrorism investigations”—5,200 terror investigations in total.70 While the domestic and international terrorism case numbers shared by Patel have somewhat declined from those shared by Wray two years prior, they still speak to an active terrorism threat environment and an overall terrorism investigation case load that has remained fairly steady, and which likely demands a considerable amount of Bureau resources.

Another way to conceive of the scale of international terrorism as a problem set is to look at who and what the United States considers a terrorist group, namely which entities it has placed on its foreign terrorist organization (FTO) list. This is a helpful high-level measure as the FTO list includes organizations that meet specific criteria, one of which is that the entity threatens “the security of U.S. nationals or the national defense, foreign relations, or economic interests of the United States.”71 So, the FTO list reflects those foreign terror organizations about which the United States has national security concerns—the terror entities it wants to keep an ‘eye on’ to monitor and, in various cases, to combat. In that way, the FTO list provides insight into how the scale, as reflected by the number and type, of foreign terror groups that are of concern to the United States is changing. It also provides insight into how the United States’ use of the FTO list as a signaling tool has been evolving, especially under the Trump administration.

The overarching change is that FTO list has expanded considerably in scale, scope, and group type. As of November 24, 2025, 24 FTOs have been added to the designation list in 2025.72 That is the single largest increase in a year since 1997 when the list was created and 28 were added. Meanwhile, only one entity was removed in 2025: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, the terrorist organization formerly headed by the new leader of Syria.73 While some entities have been removed over the years,d the number of organizations the U.S. government deems a foreign terrorist group is only growing, and substantially so over the past year.

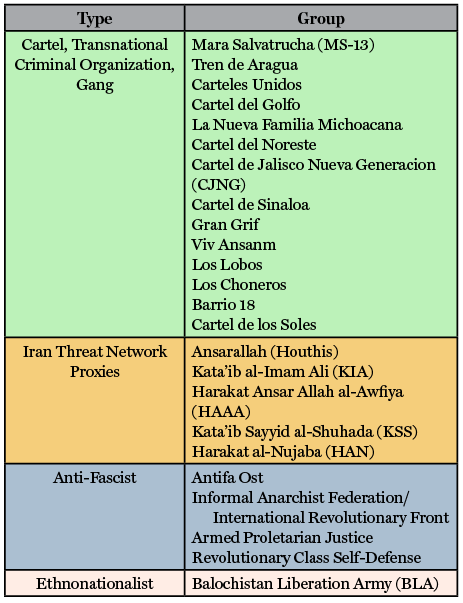

The designation of the 24 new FTOs is a seismic shift, as not only has it dramatically expanded the scale of the FTO list in terms of numbers, but it has also broadened the types of networks and groups that the United States frames as being a part of the terrorism problem set. Table 2 organizes the 24 recently designated entities into threat type categories to highlight this broadening of who the U.S. government considers international terrorists.

Table 2: Foreign Terrorist Organizations Designated by the United States in 2025

While the United States is unlikely to devote significant resources to monitor or combat all of these groups, it has signaled that some of them—such as the Mexican and Venezuelan cartels—are, and will be, a strategic priority. Thus, today, under the framework of terrorism, the United States must contend with a broad and diverse constellation of threats, which range from mainstay threats posed by core salafi-jihadi networks, such as the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida movements, to threats posed by state-sponsored or state-supported entities, principally enabled by Iran, to the recently designated cartels, transnational criminal groups, and gangs, and to a domestic terrorism landscape increasingly committed to mixed and composite ideologies.

A cross-cutting challenge is the danger posed by individual extremists—so called ‘lone actors’—who have complicated the threats posed by many of these group types over the past decade, and who also represent their own form of risk through the idiosyncratic motivations that push radicalized individuals to at times act on their own terms without ties to formal terror networks. This shift to individuals acting on behalf of groups has broadly dispersed the ‘who’ and ‘what’ counterterrorism practitioners need to monitor and investigate, which presents detection challenges and makes the task of identifying threats harder than ever before.

These dynamics have implications for how the United States will manage resources as well as prioritize attention across this universe of terrorism threats in the short-, mid-, and very likely long-term. Indeed, since each of these types of groups/threats require specialized knowledge, including geographic or other forms of domain expertise, one potential danger of the rise in the number and type of FTO groups designated is that it could stretch an already stretched U.S. CT enterprise thin. This could lead to new gaps and seams in depth of coverage, or compound existing ones, which could stress, or generate new blind spots and, by extension, vulnerabilities. It could also pose challenges or further complicate the United States’ ability to deploy limited CT assets and forces to more dispersed geographic locations, or to maintain the necessary amount of pressure or cadence of strikes and operations designed to continually attrit threats posed by mainstay networks, such as those from key Islamic State nodes. These risks could become even more acute if the campaign against cartels becomes considerably more taxing for the U.S. CT enterprise.

Speed: The Pace of Radicalization and Mobilization

A final category of evolution in the terrorism threat is speed—specifically, how long it takes individuals to radicalize and mobilize to violence. There has been much discussion of late suggesting that the radicalization and mobilization process is happening more quickly in this current environment, as characterized by the growing scale and spread of activity, and by the rapid proliferation and prevalence of online communications. This trend is further complicated by the rise in individual-driven forms of terrorism as a modality. These developments mean that counterterrorism forces have less time to identify, react, and intervene to prevent the development of a threat which—given its individual nature—can also be more dispersed.

While determining radicalization timelines is a particularly fraught exercise given the limited data available on what is an inherently private process by individuals, a handful of studies have attempted to measure these timelines. These studies generally conclude that while the increased pace of radicalization feels like a recent evolution, it has, in fact, been steadily climbing over the past several decades, with a couple ebbs and flows during that timeframe.

A November 2016 study by Jytte Klausen estimated radicalization timelines in a population of 135 American jihadism-inspired homegrown terrorism offenders convicted or killed between 2001-2015.74 This estimate measured the time between the first indication that an individual showed an interest in jihadi ideology and the time when an offender is incarcerated or engaged in a terrorism event.75 Across the full study group, the median timetable for the radicalization process was 4.2 years. After removing some extreme outliers at the higher end of the spectrum, this value was 3.2 years.76 However, the typical radicalization trajectory contracted significantly during the last five years of the study, with the radicalization process taking an average of 5.3 years during the pre-2010 period, while dropping to 1.5 years during the 2010-2015 timeframe.77

A more recent study conducted by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) compiled a database of over 3,000 extremists of all ideological persuasions who radicalized in the United States between 1948 and 2021.78 As part of this effort, researchers assessed the “radicalization to mobilization” timeframese of extremists in the 2007 to 2021 timeframe. Similar to the Klausen study, START researchers noted an increase in pace in the 2010 to 2014 period. Between 2007 and 2010, the percentage of subjects in the dataset who proceeded through the radicalization to mobilization process in less than a year hovered between 15 and 20 percent. But this number then steadily rose to just under 40 percent by 2014. Interestingly, there was a decline back down to 20 percent by 2017, but then a marked increase up to almost 50 percent by 2021.f In sum, there is empirical support for the more anecdotal sense that this problematic process is occurring increasingly fast. Although, while there does seem to be a surge in recent years, the acceleration of radicalization began at least 15 years ago, if not earlier.

Most assessments attribute the acceleration to the transformative development of online communication tools and social media applications. The Klausen study found a marked increase in the prevalence of the role of these tools occurring at the same time as the acceleration of the pace of radicalization. Of the offenders in their study who were radicalized before 2010, over 75 percent were assessed to have radicalized initially through personal contacts, while for those radicalized post-2010, it was nearly a 50-50 split between real-life sources and online inspiration.79 This timing aligns fairly well with a George Washington University (GWU) study on online radicalization that highlights the emergence of a “second generation” of online radicalization in the mid- to late-2000s, one which carried forward to the late 2010s. This generation was distinguished by the emergence of the large and public social media platforms, leading to a “more connected, user-generated internet.”80 Sharing extremist content across borders and directly linking to extremist content was revolutionary, leading one prominent analyst to claim, “Open social-media platforms changed the game.”81 As the study concluded regarding the “second generation,” “The radicalization process now infiltrated every aspect of a subject’s life, and a radicalizer could project influence into a living room or bedroom.”82

The GWU study then identifies a “third generation” of online radicalization that aligns well with the surge in radicalization speed identified by Klausen as beginning in the late 2010s. This generation is characterized by decreased importance of organizations, increased ideological fluidity, more personalized motivations, and a more chaotic online environment.83 As another study concluded:

Increasingly, the extremist landscape has fragmented into an ideologically diverse array of groups, movements, subcultures and hateful belief systems all simultaneously playing off one another. Facilitating this fragmentation is the increasingly central role of digital communications in extremist strategies, with movements using a broad range of mainstream and fringe digital platforms to organize, communicate, and plan in a decentralized fashion.84

In this most recent surge in radicalization acceleration, the dramatic proliferation of social media and the widespread use of encrypted communications tools present a dangerous combination. Social media platforms like TikTok offer ideological exposure, which can then lead to direct invitations to migrate to alternative platforms such as Instagram, Telegram, or Rocket.Chat, which offer more privacy and communication in closed or encrypted channels.85 As a recent article in this publication noted, “Such ‘safe spaces’ provide fertile ground for harder to monitor indoctrination, ideological reinforcement, and even operational planning.”86

Significantly, one of the other hallmarks of this latest generation of online radicalization is the increased prevalence of minors. The nature of this evolving information domain is tailor-made for the youth audience. As a recent study on the topic concluded, “Like no previous group, Generation Z have had their social and political life defined by social media and ubiquitous connectivity.”87 And this generation is notably tech-savvy, digitally native, and ideologically fluid.88 As described by Nicholas Stockhammer, “Short-form videos, memes, and similar stylized imagery allow radical messages to be disguised in appealing formats, making them especially effective for engaging younger, digitally native audiences.”89 With extremist content proliferating on platforms such as TikTok and Discord, and with young online gamers reporting increasing encounters with extremist propaganda, the challenge of youth radicalization is only getting worse.90 For example, German authorities have issued warnings that TikTok functions as a “radicalization accelerant” for vulnerable youth and labels the degree of this acceleration as “dramatic.”91

There is evidence suggesting that age plays a factor in the pace of radicalization. For example, a study by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service determined that among a population of approximately 100 individuals who mobilized to violence in Canada, “young adults (under 21 years of age) and minors mobilize more quickly than adults. The mobilization process for youth, especially young travellers, is a relatively minimalist endeavour … Young adults and minors generally have fewer obstacles to overcome in their process of mobilization.”92

But the issue of youth radicalization goes beyond the speed category. Circling back to the other categories of threat evolution discussed above, the perceived increase in extremist activity by children ties back to discussions about the scale, spread, and structure of the threat. Recent reporting is replete with stories about youth involvement in extremist activity. Some examples from just this month (November 2025) include:

On November 7, a 17-year-old male student in Jakarta, Indonesia, reportedly detonated an improvised explosive device inside a mosque at a school located within a naval compound, injuring 96 people. In an interesting example of the ideological diffusion discussed above, initial reporting suggests the Muslim perpetrator was actually inspired by past white supremacist and/or nihilistic violent extremist attacks, although it is not yet clear if he subscribed to any specific ideology himself.93

On November 7, German police announced the investigation of a 16-year-old suspect for sharing posts related to the Islamic State.94

On November 6, Swedish prosecutors charged an 18-year-old Syrian-Swedish dual national who was identified during an undercover sting operation and accused of planning a suicide bomb attack on a Stockholm culture festival on behalf of the Islamic State. (The investigation began a year prior, when he was a minor.) He was also indicted, along with a 17-year-old boy, for planning a murder in southern Germany in 2024.95

These recent cases are indicative of what many analysts have highlighted as a new wave of extremism among children. The proliferation of this threat has not been isolated to one geographic region. For example, in the United Kingdom, police officials issued warnings in 2021 regarding what they saw as a new wave of extremists emerging among children in the country, citing the highest figures on record for the number of underage arrests for terror-related offenses.96 By 2024, the Home Office reported that one in every five terrorist suspects in Britain was legally classified as a child.97 Britain’s youngest terror offender was sentenced in 2021 after recruiting members for a neo-Nazi group. He committed his first terror-related offense when he was 13 years old.98 Across Europe as a whole, nearly two-thirds of Islamic State-linked arrests in 2024 involved teenagers.99 This included the infamous August 2024 plot by three males aged 17 to 19 targeting a Taylor Swift concert in Vienna, Austria.100 This youth trend also extended to Australia, where “counterterrorism operations exposed a network of youth who shared a ‘religiously motivated violent extremist ideology’ and were planning an attack.”101 As a result, “Australia elevated its terror threat level from ‘possible’ to ‘probable,’ citing a heightened vulnerability in its security environment due to emerging threats.”102

The threats posed by the accelerating pace of radicalization and the disturbing rise in youth radicalization represent distinct trends in the evolution of global terrorism. These challenges, however, are tied together by the shared role played by the dramatic growth of digital communications in facilitating both trends. This is evidenced by how closely aligned the timelines of these trends are. And the fact that there is little evidence of a slowing down of the growing pervasiveness of online communication platforms suggests that both these challenges are likely to be present for the foreseeable future.

This reality poses significant challenges for the counterterrorism community. First, the ubiquity of social media access and influence, especially among youth, poses numerous challenges for society that go far beyond just terrorism. But social media platforms do seem uniquely suited to the spread of propaganda and extremism due to the unrestricted global reach, low entry barriers, their capacity for anonymity, and their algorithm-driven content delivery.103 It is essentially impossible for law enforcement to slow the spread of this material, as monitoring tools struggle to keep pace with the proliferation of messaging and content moderation efforts suffer from numerous limitations, both legal and practical. Second, the ease of access to end-to-end encrypted messaging tools by potential extremists make it increasingly difficult for counterterrorism practitioners to get inside terrorism plots and monitor the activities of radicalizing individuals. Finally, the increased speed of the radicalization process means that law enforcement and intelligence professionals are faced with an increasingly narrow window of time to overcome the increasingly difficult challenges just outlined.

The Changing Character of U.S. Counterterrorism

Since 2018, the U.S. CT community has been undergoing change and trying to identify what ‘CT right’ looks like. This period of transition has been characterized by “a shift in U.S. national security priorities; a complex, diverse, and ever-evolving threat landscape; and ongoing technological change that is transforming the worlds of extremism, terrorism, and counterterrorism.”104 A defining aspect of this period has been the prioritization of strategic competition as the leading U.S. national security priority, a shift which has led to a reduction in emphasis and resources devoted to counterterrorism. As a result, the U.S. CT community had to streamline; navigate tradeoffs; and innovate, modernize, and evolve. This transformation, which is still underway, has not always been easy, as it has been challenged by several points of tension.

U.S. CT in Transition: Key Considerations, Benefits, Drawbacks, and Tensions

The section examines how the United States has been trying to ‘right size’ CT over the past several years; how key factors have been shaping the direction, reach, and pace of change; and how dilemmas and points of tension have complicated and challenged the U.S. efforts to optimize CT and find a sustainable CT path.

In Search of Sustainable CT

Since at least 2018, the U.S. national security enterprise has been grappling with a key overarching question: What does a sustainable CT posture and commensurate level of CT resourcing look like and how can that be achieved?105 The United States recognizes it needs to spend less time and resources focused on counterterrorism so that it can prioritize more strategic and capable threats, such as the pacing threat that China poses to the United States in various areas. This recognition led to what was arguably an overdue shift in 2018, whereby terrorism was identified in the National Defense Strategy (NDS) as a secondary, but still important and persistent, national security priority.106 Since that time, the U.S. CT community has been trying to figure out what ‘CT right’ looks like during this era, and what level of resourcing, focus, and CT activity is required to sufficiently degrade and keep the threats posed by the Islamic State, al-Qa`ida, Iran and its proxy network, and other actors with international terrorism ambitions at a low enough level.

This has not been the easiest thing to do in practice. At a base level, there have been different views and debates about just how much CT matters given the nature and scale of threats posed by a rising China and other state adversaries. For example, CT and strategic competition “are often analytically bifurcated or siloed in the U.S. context and are routinely viewed, prioritized, and resourced as two distinct priorities or problems.”107 While those distinctions can at times be helpful, they have also challenged U.S. efforts to look across these two priorities to identify “how and where these two priorities interplay and converge,” so investments in each priority can be optimized and service the other when appropriate.108

Some of the United States’ most vexing national security challenges involve the deep blending of both priorities—whether that is how Iran instrumentalizes terrorism as a core part of its foreign policy; how terrorism has been a key driver of violence and instability across the Sahel and West Africa; or how CT assistance has been a longstanding pillar of the United States’ defense alliance with the Philippines, a nation whose strategic location would be important for any Taiwan or China-related contingency.

In these pages last year, one of the authors introduced the CT Return on Investment (CT ROI) Framework: a “conceptual tool designed to help decisionmakers and their staff to understand and map returns from counterterrorism investments, and to situate how those investments intersect with and can provide value to strategic competition.”109 A primary contribution of the framework is that it illustrates how CT activity functions as a form of threat mitigation and how it has also “evolved as a form of influence” that the United States can leverage to shape or achieve strategic competition goals.110 For example, while the United States would like to move on from terrorism, for many partners—or potential partners—terrorism remains a preeminent security concern. Over the past two decades, the United States has developed a considerable amount of hard-earned CT currency, and it should leverage that currency to achieve other goals. It would be a mistake not to do so.

The United States is still living through and learning lessons about how prior policy decisions may have overlooked the ways in which CT and strategic competition nest. For example, in September 2025, President Trump made headlines after stating the United States wanted to get Bagram airfield in Afghanistan back from the Taliban. For two decades, Bagram functioned as a key logistical hub for U.S. CT activity in the country. According to The Wall Street Journal, Trump administration officials “are in discussions with the Taliban about re-establishing a small U.S. military presence at Afghanistan’s Bagram Air Base as a launch point for counterterrorism operations.”111 The push is reportedly a “potential component of a broader diplomatic effort to normalize relations with the Taliban,”112 but comments made by President Trump hint at other strategic motivations. In talking about Bagram, for example, President Trump noted how: “It’s an hour away from where China makes its nuclear weapons” and “where they make their missiles.”113 From a strategic competition perspective, Afghanistan is a key location for U.S. forces and assets to be postured for missions that involve Iran and China.

The quest to find the right balance—a sustainable U.S. CT posture—has been a work-in-progress, and it has been complicated by various factors. For example, while the United States has been eager to make the shift and fully transition international terrorism into being a less resource-demanding problem, key terror networks also unfortunately get a say. Over the past decade, terror networks have found ways to disrupt the shift, and strategically distract the United States, even if only for limited periods. The tragic terror attack on October 7, 2023—a single event that ignited tensions and broader regional conflict in the Middle East, the repercussions of which still reverberate today—is an important case in point. As noted by Christine Abizaid, the former NCTC Director, the disruptive impact of the attack for the United States was profound:

We spent a lot of time trying to narrow our focus to only those most urgent threats to Americans. If a group wanted to conduct attacks against Americans, they were going to go to the top of our list. And yet, a group that wasn’t necessarily interested in attacking Americans set off a chain of events in the Middle East that caused one of biggest strategic challenges for us as a country over the last couple of years.114

Another key complicating factor has been fluctuations across administrations about how CT challenges should be handled—the approaches, instruments of power, and tools that should be prioritized, and at what levels. For example, in 2023, Nicholas Rasmussen—President Biden’s DHS CT Coordinator—remarked that the United States was “in a place where we are less reliant on a strategy where we will be using aggressive direct action in the overseas environment to deal with counterterrorism threats.”115 That shift was reflected in National Security Memorandum 13 (NSM-13)—a key document that strategically guided the Biden Administration’s CT approach—in which “Narrowly Focus Direct Action CT Operations” appeared as Line of Effort 4 after “Strengthen Defenses,” “Build and Leverage Partner Capacity,” and “Strengthen Capacity to Warn.”116 To help support Line of Effort 1—“Strengthen Defenses”—the Biden administration placed emphasis on domestic terrorism prevention as an important component of its strategy. Since January 2025, the Trump administration has prioritized other CT approaches by placing greater emphasis on offensive direct action, border security,117 and illegal immigration; less emphasis is given to terrorism prevention programs. While some level of change in how the United States engages in CT is expected across time, and is the prerogative of any administration, the fluctuations and lack of consistency across time make it hard for the U.S. CT enterprise to mature efforts and develop efficiencies.

on February 9, 2023. (Master Sgt. Michael Matkin/U.S. Department of War)

Not long after the release of the 2018 NDS, the United States started to scale back the level of resourcing for CT so more personnel and assets could be redirected to the China mission set and other priorities. Across time, this has “meant that there have been less resources across the U.S. government for counterterrorism.”118 It has also meant that the U.S. “counterterrorism enterprise and community [has had] to make harder choices about where resources can be devoted.”119

The reduction in resources has had several positive benefits. Overall, it has been a good forcing function to initiate and drive change across the U.S. CT enterprise. It has pushed the United States to be more rigorous about how it prioritizes international terrorism threats, and what networks or threats require, or are more deserving of, U.S. CT attention, which is in more limited supply. As part of that effort, it has also pushed the United States to focus “on disrupting and degrading only the most dangerous VEOs (those demonstrating intent and capability to attack the U.S. homeland), while allocating fewer resources toward disrupting and monitoring VEOs which present a regional and/or local threat to U.S. interests.”120 The United States cares about these other terrorism threats, but at the end of the day, what matters most is protecting the U.S. homeland and the American people.

Less resources devoted to CT has also pushed the United States to identify and minimize areas where resources were not aligned with core CT priorities, where CT efforts were ineffective, or where the U.S. interagency had unnecessarily redundant, or overlapping, capabilities. The concern about CT ‘bloat’ and duplication of effort has been highlighted by researchers121 and been a subject of congressional testimony. In 2018, during his nomination to be the next NCTC Director, Vice Admiral (Ret) Joseph Maguire fielded questions driven by concerns about redundancies and the growth and size of different NCTC directorates.122 While some level of redundancy can be helpful,123 these efficiency initiatives have generally helped to streamline and optimize the U.S. CT enterprise. But, at the same time, there have been concerns that some of these initiatives may have gone too far, as some have argued that they have eroded important CT capabilities.124 Meanwhile, the reduction in manpower devoted to CT has also given new urgency to data and other modernization initiatives.

The CT resourcing environment has pushed the United States to lean more on partners to burden-share, by asking, or requiring, them to do more or take more ownership of localized terrorism challenges. As noted in NSM-13: “Foreign partnerships, already a key component of U.S. CT strategy and efforts, will take on increased importance.”125 This “will help to spread the CT resource burden” and enable the United States—at least in theory—to “leverage complementary CT capabilities and efforts, and produce more enduring results by empowering partners to assess, prevent, and mitigate terrorism threats in their own countries and regions.”126 Overall, the increase in emphasis placed on burden-sharing as a pillar of U.S. CT strategy during the Biden and Trump administrations is designed to offset the management of risk and “make U.S. counterterrorism efforts more sustainable.”127

While the theory of CT burden-sharing has emerged as an important pillar of U.S. CT strategy, the track record of U.S. CT burden-sharing efforts have been more mixed in practice. Part of the reason, as noted by Christopher Maier, former Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict, is because:

There’s a balance between being able to be proximate enough to be able to mitigate some of these threats and being able to do that with our partners and allies. In many cases, we’re talking about partners who are not that capable, often dealing in a semi-permissive, if not permissive environment, for these non-state actors or CT problems because there’s fundamentally not a lot of governance in these places.128

In many cases, this has made it hard for the United States and its varied CT partners to translate tactical gains into strategic and sustainable gains. While areas of success are apparent—for example, the United States’ partnership with the SDF was critical to the territorial defeat of the Islamic State in Syria and is largely viewed as an overarching CT success—challenging, or more mixed cases, are also easy to find. While the United States developed effective CT units and partners that achieved important tactical gains in Afghanistan and Iraq, the capacity and willingness of both governments to progressively manage and take broader ownership of the CT fight, and to translate tactical gains (along with the United States) into strategic wins was limited. In the Afghanistan case, the result was a collective security failure and the collapse of the Afghan government. In Iraq, the results have been more nuanced. The poor performance of Iraq’s security forces was a key factor that led to the rise and territorial expansion of the Islamic State in 2014, but Iraq’s CT forces were also a key partner that helped to enable the defeat of the network and to generally contain the Islamic State’s violence in Iraq since.

CT resource constraints have pushed the United States to explore and get more comfortable with tradeoffs, including by investing in non-traditional CT partnerships. The United States’ CT cooperation with the new Syrian government129 and areas where the Taliban regime and United States have shared threat concerns130 speak to this. The environment has also helped the United States to strengthen ties and cooperation with other mixed record partners, such as the Pakistani government, to attrit and degrade the capabilities of groups such as ISK where there is mutual interest.131

But the reduction in resources for CT has also had downsides, as it has created, or compounded, various challenges. One high-level impact is that it has led to less manpower and bandwidth devoted to CT, which has affected the number and type of threat networks the U.S. CT community can monitor, or at least monitor closely with less tradeoffs. The danger is that this could create blind spots, especially for groups such as Hamas or Lashkar-e-Taiba that are primarily driven by local and regional interests, but that have also explored and taken steps toward international terrorism.132 It could also limit the United States’ ability to monitor, evaluate, and keep close tabs on other known risks such as the detention of ~10,000 Islamic State prisoners in northeast Syria.133

The erosion of expertise—which has been driven by multiple causes including retirements and natural attrition, the movement of personnel to other priorities, and CT manpower cuts—has compounded the challenge. Today, not only are there less people working in CT, but there are also less seasoned experts still working on this complicated and evolving problem set. A danger is that this could lead to gaps in knowledge, inefficiencies, and vulnerabilities especially as the number and type of terror groups that the United States needs to monitor expands.

Importantly, the reduction in resources has led to changes in the posture of U.S. CT and how the United States assesses and accepts terrorism risk. As noted by Matthew Levitt: “By definition, shifting away from two decades of counterterrorism premised on an aggressive forward defense posture and toward one more focused on indicators and warning means assuming some greater level of risk.”134 The shift has had practical impacts, which have complicated the ability of the United States to ‘see’ and make sense of key threat environments, and develop options for CT activity. For example, as noted by Russ Travers in 2019: “As we draw down military forces we will have less human intelligence and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capability in theater. There will be less liaison with on the ground partners.”135 In addition to affecting collection strategies, this has meant that terrorism risk assessments, which have always been an important part of U.S. CT strategy during the post-9/11 era, have become even more important. The enhanced emphasis placed on risk is reflected in NSM-13 and in statements by senior U.S. CT officials. In 2023, for instance, the DHS Coordinator for CT noted how the Biden administration’s “counterterrorism strategy focuses more on risk management and risk mitigation.”136 It also was oriented around a more “defensive counterterrorism strategy” that had “much less margin for error.”137

It was a shift that the United States did not always get right at the time, as there were some close calls. The most noteworthy case was the arrest in 2024 of eight Tajik nationals over terrorism concerns and suspected ties to Islamic State members after they had entered the United States through its southern border.138 According to The New York Times, “heightened concerns about a potential attack in at least one location triggered the arrest of all eight men … on immigration charges.”139 The incident raised alarm bells in the counterterrorism community because even though nothing tragic happened, the layered system that the United States has constructed to prevent acts of terror only caught the individuals “on the last line of defense—after they were already in the United States.”140

These types of close calls have also been an issue in Europe. For example, in the United Kingdom between 2017 and 2024, “Police and security services … [in the U.K.] stopped 43 late-stage terror plots …, three of which were in [2024] … with some of these being ‘goal line saves.’”141 These dynamics highlight the persistence of the terrorism threat and how shifts in focus, resources, and risk tolerance have been stressing on the ability of CT elements to detect and disrupt threats at earlier stages of planning.

Shifts in resources have also led to other important changes in U.S. CT orientation and capabilities. For example, in 2021, the focus of Joint Task Force Ares—a key Cyber Command task force that was created in 2016 to degrade and disrupt Islamic State and other terrorist activity online—changed its primary point of orientation. As noted by the commander of U.S. Cyber Command at the time: “We are also shifting JTF-Ares’ focus (though not all of its missions) from counterterrorism toward heightened support to great power competition, particularly in USINDOPACOM’s…area of responsibility.”142 Resourcing shifts away from tacking online dimensions of the terror threat have been compounded by cuts and a similar general reduction in focus across the private sector. For example, Adam Hadley, executive director of Tech Against Terrorism, recently noted that online terrorist content is no longer a major focus at tech companies.143

Decisions about CT resourcing have also been challenged by changing security conditions and the actions of adversaries in key areas that affect the conduct and logistics of U.S. CT. One area where this has been felt is airborne ISR. As noted by Christine Abizaid, the former Director of NCTC, during an interview in this publication in 2025:

We have limited airborne ISR, we have limited strike capacity that can reach various parts of the world, we have a range of threat actors and associated plotting against the United States, and so this also becomes a cost-benefit analysis of how you use your precious resources to best effect when you’re dealing with a diverse array of threats.144

Global events have certainly challenged and stressed this limitation even more. For example, in 2024, the Department of Defense lost access to a key military base in Niger “5 years after building a $110 million drone base” in the country.145 The impact was that the United States’ “ability to conduct ISR within the Sahel … has been severely degraded.”146 It has also been reported that during Operation Rough Rider, the Houthis downed at least seven MQ-9 Reaper drones, “a loss of aircraft worth more than $200 million.”147 These are not insignificant losses, and they likely have a bearing on where and how the United States can engage in CT.

Another downside of CT cuts is that modernization is not a switch. It takes time and considerable resources to build, test, and refine new systems and pipelines, and to integrate and educate the force about new processes and technologies developed for CT.148 It also requires the right type of talent. This has arguably led to a point of tension: The U.S. CT enterprise needs to modernize and accelerate existing modernization efforts so it can optimize; but it is not clear, given the resource environment for CT, that it has the appropriate level of resources and time to do so at the scale and speed needed.

While the full impact of multi-year cuts to the U.S. CT enterprise is not yet known, there are ongoing debates about what CT ‘right’ looks like. One concern that has been expressed is the danger of overcorrection,149 as recent goal line saves in the United States and Europe illustrate how there is not much room for error. There is also the need to avoid, and fight against, complacency; a self-initiated threat that always lurks. In the months and years ahead, the United States’ quest to find the right balance will also need to contend with the broadening of CT priorities and focus areas under the Trump administration, and how that impacts the work of the CT community in practice. As noted in the first section of this article, not only are there now more FTO-designed groups that the U.S. CT enterprise needs to monitor, but the different types of groups represented require different forms of expertise and the potential, broader geographic spreading of limited U.S. CT assets, capabilities, and manpower.

As others have noted, for the United States, part of the pathway forward to sustainable CT lies in recognizing that while there have been challenges and failures, “what we have built works, and it’s not broken … it’s important to identify and reinforce the successes we’ve had in the CT sphere.”150 Thus, while embracing change and evolving U.S. CT are critical parts of the way forward, those factors should be balanced against consistency and “a sustainable investment in a community of professionals whose only job is to focus on CT and to tell policymakers when it’s time to take action against our worst terrorist adversaries.”151

The future of U.S. CT will also need to contend with other important shaping factors. For example, compared to a decade ago, today’s CT landscape contains a broader and more diverse mix of “stakeholders or ‘players’ who either have been meaningfully shaping, or have a role in, the world of counterterrorism and how specific counterterrorism actions or responses take place.”152 This includes states such as Turkey, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates that are playing more assertive and in some cases central roles in the CT arena, and also nations like China and Russia that are leveraging CT as a form of influence in key areas to achieve their own interests, or to contest, counter, or provide an alternative to U.S. presence and access in strategic areas. It also includes the rise and development of commercial counterterrorism as a sector, and how non-state actors and private companies, such as technology platforms, have been shifting who “designs, manages, owns, and has access to, or influence over, specific platforms and approaches.”153 For instance, when it was founded in 2017, the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism had four private sector members; by 2025 that number had grown to 33. Thus, a core driver of the future of U.S. CT is going to lie in how the United States situates itself and leads, or does not lead, in this more complicated CT landscape that is more saturated with equities, opportunities, competitive dynamics, and risks.

How the United States approaches partnerships will be an important barometer to watch, as while the United States has spent the last several years streamlining its own priorities and optimizing how the interagency engages in the practice of counterterrorism, there are a lot of opportunities for the United States to learn from, to enhance, to integrate with, and to optimize how it engages with and makes strategic and operational use of private sector partners. It can even be argued that the future evolution of U.S. CT will be conditioned on how the United States optimizes these types of relationships, as the potential they hold could unlock and radically transform the speed and efficiency of counterterrorism, and better position the United State to respond and deal with the challenges posed by the evolving spread, structure, and scale of terrorism noted earlier.

Conclusion

U.S. CT must contend with changes and complexity associated with the spread, structure, scale, and speed of terrorism threats. This is not an easy task because over the past several years, the U.S. CT enterprise has been determining what CT ‘right’ looks like during an era with less resources and lower prioritization. As the United States continues that quest, it is important that it evolves intentionally in relation to key changes and trends affecting the terrorism threat environment. This is important because changes across the four terror threat factors—spread, structure, scale, and speed—could either complicate U.S. CT efforts or demand greater U.S. leadership and attention in the future.

When it comes to spread, the United States and its partners have had to contend with a geographic shifting of terrorism to other regions, such as the Sahel, over the past several years—a dynamic that has expanded the portfolio of threat networks that need to be understood and more closely monitored. This shift has created other geographic concentrations, fronts where affiliates of older mainstay jihadi networks have found space to control sizable amounts of territory, threaten local governments and regional stability, and conduct operations across borders. In the Sahel, an area where the U.S. government has less knowledge, influence, and reliable partners, it appears—absent some type of arresting mechanism—that JNIM is poised to expand its area of influence, consolidate areas of local control, or both, a dynamic which is likely to further complicate the trajectory of terrorism in the region, and potentially beyond, in the near- to mid-term.

The evolving structure of extremism and terrorism presents similar challenges. It can be argued, as some researchers have, that the Islamic State has evolved its own structures in response to CT pressure. That is an important win. But it is also important for the United States to take stock of those changes and reflect on where additional shifts may be needed to counter those Islamic State movement adaptations, especially when they pertain to external operations, which are increasingly multi-vectoral. The fact that the primary terrorism threat that the United States has had to contend with over the past several years is attacks from individuals and small cells similarly illustrates just how far the United States has come in fracturing the capabilities of key terror organizations, primarily al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State. Yet, there are lessons to be learned on this front, too, as while the Islamic State’s general dependence on inspiring—and to a lesser extent enabling—radicalized individuals to conduct acts of terror on its behalf is a sign that things have been ‘working,’ the persistent ability for the Islamic State to remain an attraction and a source of inspiration highlights how the fight is far from over. The evolving ways in which terror networks have been looking past ideological distinctions and practically collaborating with other terror networks, criminally motivated individuals and entities, and states is also an issue that has been affecting the character and structure of threats, and it seems likely that it may also be a driver that shapes its future evolution and form.

One seam that may need tightening is how offensive and defensive aspects of CT are synchronized. For example, it is important that kinetic pressure placed against key international terror networks abroad is disrupting key nodes generally, but that it also diminishes their ability to engage in ‘reach’ online and to inspire, enable, and shape the actions of sympathizers back ‘home’ and in other nations. It is ironic that at a time when the Islamic State needs to rely on its online presence more, U.S. and international efforts focused on terrorism activity in this domain do not appear to be as strong as they have been in the past.

To improve security, it is also important that offensive ‘away’ CT activity be bolstered by stronger defensive CT measures that lean forward in a similar way. The domestic legal frameworks that guide counter small unmanned aerial systems activity is one area where stronger defense capabilities and measures are not just appropriate but needed and would likely go a long way in complementing U.S. CT efforts to mitigate the threat abroad.

Public-private partnerships hold a lot of potential and are a key area where U.S. CT activity can be further optimized to enhance or evolve existing approaches; better tackle areas, such as terror activity online or drone countermeasures, where additional assistance would likely be helpful; and develop new methods. The embrace of these forms of collaboration and partnering will likely lead to more efficient CT; it could also lead to new CT structures and changes in how the U.S. government organizes itself for CT.

The scale of today’s terrorism threat, as reflected by the number of attacks and diversity of terror networks that want to harm the United States, has meant that U.S. efforts to prioritize terrorism threats—where and when it can devote time and resources—are more important than ever. The steady number of terrorism cases in the European Union and United States over the past several years also highlights how considerable resources are required to ‘hold the line’ and keep the number of terror attacks at low levels, despite core al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State having been significantly degraded and diminished.

It is still too early to know how the addition of 24 new entities to the foreign terrorist organizations list by the Trump administration in 2025 will affect the issue of scale. Also unknown is how it may impact the spread and deployment of U.S. CT forces, or how it may divert U.S. CT attention from other terrorism threats over the short- to mid-term.

To help manage the challenge of scale and offset terror risk, the United States has placed greater emphasis on CT burden-sharing, with a mixed record of success. In some cases, this has required that the United States get more comfortable with tradeoffs and prickly alliances oriented around common threats. For example, the United States’ CT cooperation with the new Syrian government has thus far been productive, and depending upon how it evolves, it may end up being a key model that it looks to emulate elsewhere.

In today’s environment, thanks to the transformative impact of technology, speed effects nearly everything, and it has created challenges and opportunities for terrorism and CT. The U.S. and global CT communities are still navigating how to deal with the increased speed of radicalization and the shortening of time it appears to be taking for radicalized individuals to mobilize. The trend, which seems likely to continue, has made it harder for CT investigators to identify who presents a threat from a broadening sea of ‘noise’ and respond at commensurable speed. Technological change has also lowered the barriers to entry and made it easier for youth and minors to access and engage with extremist content, which has led to an unfortunate rise in terrorism cases involving minors in many nations.

While not fully here yet, speed also lurks as an operational terrorism threat vector. It is not hard to find evidence, from the accessibility of capable fast-moving FPV drones that can be purchased readily online to tactical knowledge about how drones are being operationally used and weaponized in Ukraine, to see that drones moving at speed will shape the future of terrorism too. But, if the United States embraces and wields technology right and leads with vision, speed can also be a force multiplying asset and help the United States to optimize the structure, scale, and spread of its response to the complex and varied terrorist threats it will face tomorrow and further into the future. CTC

Don Rassler is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Sciences and Director of Strategic Initiatives at the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy. His research interests are focused on how terrorist groups innovate and use technology; counterterrorism performance; and understanding the changing dynamics of militancy in Asia. X: @DonRassler

Kristina Hummel is co-Editor-in-Chief of CTC Sentinel and an Instructor in the Department of Social Sciences at the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy.

Brian Dodwell is the Executive Director of the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Social Sciences at the United States Military Academy. He has conducted research on various topics, to include Islamic State affiliates, foreign fighters, jihadi terrorism in the United States, and U.S. homeland security challenges.

Major Ned Curry teaches courses in terrorism and international relations in the Department of Social Sciences at the United States Military Academy. An Army Reserve Intelligence Officer, he previously worked for the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations at the State Department (2019-2025).

© 2025 Rassler, Hummel, Dodwell, Curry

Substantive Notes

[a] Those countries are Burkina Faso, Pakistan, Niger, Syria, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Cameroon, and Russia.

[b] These two attacks were among the 10 deadliest terrorist attacks of 2024. See “Global Terrorism Index 2025,” Institute for Economics & Peace, 2025, p. 94.

[c] If data from Myanmar is included, “the number of terrorist attacks dropped by three per cent” over the same time period. As noted by the Global Terrorism Index, that drop was “primarily driven by an 85 per cent reduction in Myanmar.” “Terrorism is spreading, despite a fall in attacks,” Vision of Humanity, March 4, 2025.

[d] Twenty-one entities have been delisted since the list’s inception, though one of those is Ansarallah (the Houthis), which was designated in January 2021, delisted in February 2021, and subsequently redesignated in March 2025. See “Foreign Terrorist Organizations,” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Counterterrorism, n.d.