Abstract: It has been more than 10 years since Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi ascended the pulpit in the al-Nuri mosque to announce that the group known as the Islamic State had, at least in its own eyes, fulfilled the requirement to become a caliphate. In doing so, he opened an era of expansion for the Islamic State in which it welcomed numerous affiliates into its fold from all over the world. While some of those affiliates remain to this day, others appear to have faded away, at least when it comes to carrying out operations. This article explores these “repressed” affiliates in an effort to provide a brief overview of potential reasons behind their decline. The stories of each of these affiliates contain both similarities and differences. The repression of Islamic State affiliates seems to be the result of a combination of factors, ranging from military power of external actors to in-group conflict to an inability to gain a foothold among a target population. The importance of nuanced counterterrorism efforts, as opposed to a one-size-fits-all approach, is the main takeaway of this analysis.

When the group known as the Islamic State announced itself as a new caliphate in the summer of 2014, it did so with a call to groups and individuals from around the world to join its cause.1 Many groups and individuals responded, creating a perception that the Islamic State had established a large network of affiliates committed to its cause, one that would also serve as a test of the group’s overall success or failure.2 Indeed, even as the group began to experience increased military pressure from local and international forces in late 2014, it released its flagship propaganda product, Dabiq, with the bold headline of “Remaining and Expanding,” suggesting that its network of affiliates demonstrated its staying power. In the many years since this period, even as a number of caliphs have been killed, the group has continued to rely on this network of affiliates to reaffirm its relevance and presence, as demonstrated by the fact that the group highlights all of the affiliates who release statements confirming their allegiance to the newest caliph.3

Of course, public pronouncements of support are not the only source of support that affiliates provide to the Islamic State’s global brand. Unfortunately, some of these affiliates have proven themselves to be incredibly capable of carrying out tremendous acts of violence, both inside the borders in which they have their base of operations as well as beyond those same borders. For example, the Islamic State’s affiliate in the Lake Chad basin, known as Islamic State – West Africa Province (ISWAP), carried out a deadly attack on a village in Nigeria that left as many as 170 residents dead.4 When it comes to attacks beyond the affiliate’s home base, perhaps the most prolific example is Islamic State Khorasan (ISK), which has carried out several high-profile attacks beyond the borders of Afghanistan and Pakistan.5

However, the activity of some of the Islamic State’s affiliates should not obscure the reality that several of the group’s other affiliates appear to be incredibly limited in their ability to carry out attacks. Yet, despite the potential lessons to be learned from examining the cases in which affiliates have struggled, there has been comparatively less work at these affiliates as an analytic category. The author argues that these affiliates that have struggled are important to study and can potentially provide insight into what strategies may ultimately be effective in fighting against these types of organizations or whether their reduction in operational activity appears to be out of the control of counterterrorism efforts. Additionally, there is value in looking at the examples in which the Islamic State affiliates have effectively disappeared from the public mind in terms of attacks, if for no other reason than to remember that, despite some of its successes, the Islamic State, even with a large network of affiliated organizations, is neither inevitable nor invincible.

In what follows, the author first discusses the methodology used to identify the Islamic State affiliates that make up the population of study in this article. These are referred to as “repressed” affiliates in an effort to indicate that their operational activity has significantly declined or ceased according to some metrics. Then, the author proceeds to discuss each affiliate in terms of four categories: brief summary, reflections on current status, counterterrorism activities, and other considerations. It is important to explicitly state upfront that the goal of these examinations of each group is not to provide an exhaustive or comprehensive account of their history. Many other scholars, experts, and practitioners are better qualified and positioned to do this type of valuable work. Instead, the goal here is to prime conversation and thought about select factors and issues worth considering when it comes to the decline of these affiliates. After the discussion of each of the individual affiliates, the article concludes with an overview of the commonalities and differences that stood out between the circumstances surrounding the decreased activity of each of the affiliates.

The Repressed Islamic State Affiliates

As noted above, the Islamic State’s network includes activities carried out by core groups located in the group’s original stronghold of Iraq and Syria (referred to here as the Islamic State – Core or ISC), affiliates, and individuals who view themselves as operating in the group’s interest although they are not formal members of the core or affiliates. The study here focuses on the second group, the affiliates. Obtaining a count of the total number of affiliates is difficult, in part because affiliation may be extended by a group, but not accepted by ISC. Moreover, ISC has in some cases had distinct entities that it and others have referred to under a lump entity. For example, when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi announced the establishment of the group’s affiliate in Libya, he did so by designating three provinces: Barqa, Fezzan, and Tripolitania.6 Yet, after time, most analysts simply referred to these three entities as the Islamic State in Libya, even though the entity itself still utilized separate province names from time to time.7 Then, in one of the affiliates’ communications in support of a new Islamic State caliph in 2022, the propaganda product referred to Libya alone, with no other geographic distinction.8

Though issues like these make a total count of affiliates, past and present, difficult, the relevant point for this article is that there are more than just one or two prominent affiliates, and that not all of them appear to be equally active when it comes to operations or other activities. The goal here is to identify a group of what the author refers to as “repressed” affiliates, which is taken to mean an affiliate that has been formally recognized by the group, but which, despite carrying out attacks in the name of the group previously, has been unable to do so for a length of time. One may wish to call these affiliates “failed” or “inactive,” but such nomenclature is dangerous when applied to affiliates. Because they are clandestine, it can be difficult to measure when they have truly ceased to exist, especially when relying on open-source information. The danger in declaring a terrorist group to have ended, failed, or to be inactive based on a lack of visible attacks, comes in the case where a lull in attacks may simply be a strategic move by the group to avoid scrutiny in an effort to rebuild and launch future attacks. As will be demonstrated below, there are cases in which a lack of claimed attacks may not tell the full picture regarding an affiliate’s potential.

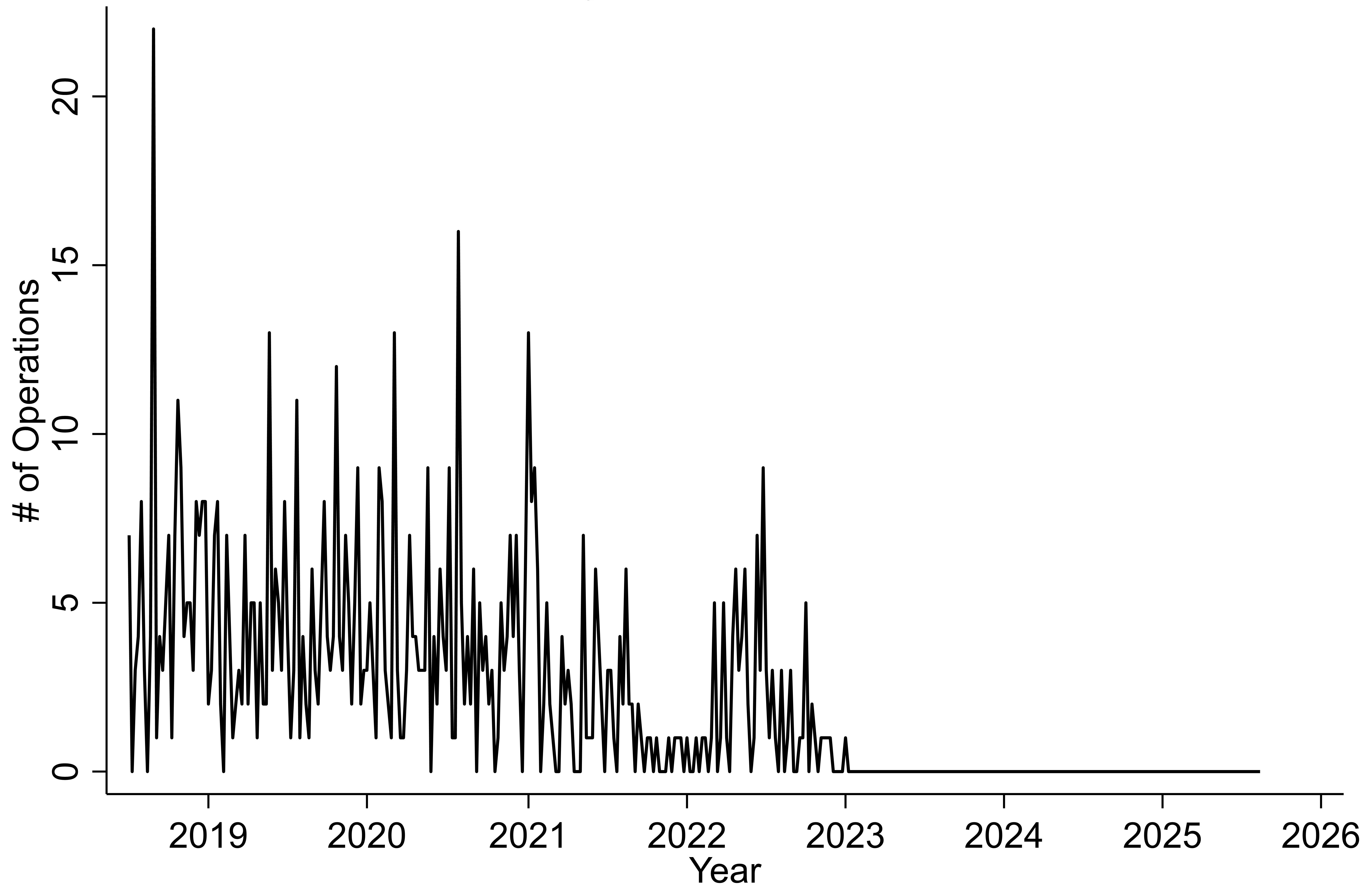

Recognizing these challenges, this article avoids labeling affiliates with a designation that conveys a sense of finality and instead refers to the sample of interest as “repressed” affiliates. The intuition behind this label is that it suggests demonstrated diminished level of operational activity, but does not necessarily indicate that an affiliate has gone out of existence. To determine whether an affiliate is repressed or not, the author first takes the list of affiliates as contained in Islamic State’s public claims of responsibility for activity as contained in the group’s Al Naba weekly periodical. Al Naba contains, among other things, interviews, written articles, and, most importantly for this study, a list of incidents that the group has claimed throughout its network. Using this text as the source, the author then identified affiliates for which the group has not reported any operations for at least 12 months prior to the end of the data collection (August 2025).a Those affiliates that meet these criteria are as follows: Algeria, Caucasus, India, Libya, Saudi Arabia (which consists of the Islamic State’s affiliates in Hijaz and Najd), Sinai, and Yemen. Table 1 provides an overview of these groups, including the month and year in which Al Naba last claimed an operation on behalf of the group.

Table 1: Islamic State Repressed Affiliates as of August 2025

Relying on Al Naba claims of responsibility for operations is not without potential weaknesses or shortcomings. The first is that it is difficult to know how reliable it may be as a source, whether as a result of strategic underreporting by the group due to counterterrorism concerns, difficulties in communication between various elements of the group (ISC and the affiliates, for example), or due to other intra-group conflict dynamics.9 For example, even though Al Naba has been released with a fair amount of consistency for many years, the network of individuals that contribute to and produce it may be faced with counterterrorism or other pressures that lead to disruptions in the timing and scope of their individual reporting. The second is that this data might not contain failed plots or other indicators of group activity, which can lead to a biased analysis.10 These are all important points to keep in mind and further support the decision not to label affiliates as failed based off of Al Naba reporting alone. Moreover, to mitigate some of these concerns, other forms of data (including government reports and media reporting) are included in the subsequent analysis in an effort to avoid privileging the Islamic State’s own reporting. Although Al Naba reporting provides the initial list of affiliates and those with diminished operational activity, it is not the sole source of data in this article.

Islamic State in Algeria

Brief Summary

On September 14, 2014, media reports emerged that a group of fighters had left al-Qa`ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), formed a new, but distinct group, and then pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.11 Less than two weeks later, a video emerged in which the Algerian branch of the Islamic State executed a French tourist, Hervé Gourdel, who had been hiking in the region.12 Despite carrying out several other operations after this point, the group quickly declined in numbers and in activity, only carrying out sporadic attacks, including four in 2017, one in 2019, and then its last claimed operation as reported in Al Naba in February 2020.13 In the other words, the operational pace of the Islamic State’s Algerian affiliate had slowed down long before 2020.

Reflections on Current Status

Very little has been heard from the Islamic State – Algeria since its last attack 2020. Despite the silence, there have been a few indicators from other sources that the group may still be operational. In a 2023 report by the U.S. government on terrorism in Algeria, it was noted that “ISIS’s Algeria branch, including the local group Jund al-Khilafah in Algeria, remained in the country – though in ever-smaller numbers, as they have been unable to attract new recruits or significant new resources.”14 Two years later, in a U.N. report, it was noted that Algerian security services had resulted in “the detention of ISIL (Da’esh) supporters involved in propaganda.”15 Even though minimal, these statements are somewhat surprising, especially given the fact that the affiliate has not claimed an operation for several years. Still, reports from Algeria recently claim arrests of “terrorists,” though they are vague and do not tie the individuals publicly to any group or ideology.16

Counterterrorism Activities

To explain this decline, several analysts have pointed to the forceful and sustained operations carried out by the Algerian government against the Islamic State affiliate, which also appears to have dealt similarly with AQIM in the country.17 Of particular note, in December 2014, merely a few months after Gourdel’s execution, the Algerian government’s counterterrorism operations resulted in the death of the leader of the Islamic State affiliate, Abdelmalek Gouri.18 The subsequent year, 2015, the U.S. State Department reported that the Algerian government had killed or arrested 157 terrorists during the year, although it did not provide a breakdown of how many might have been associated with the Islamic State as opposed to other terrorist groups.19 Subsequent reports from the U.S. government did not identify specific numbers of arrests or deaths as a result of Algerian efforts, instead only noting that terrorist groups, including the Islamic State’s Algerian affiliate, “were under considerable pressure.”20 For its part, the Algerian government, again without distinction, claimed to have reduced the ranks of terrorists by 500 from 2015-2018.21 These efforts have been supported by the U.S. government, which has engaged in intelligence sharing and military support with Algeria.22

Relying on military and law enforcement is only a part of Algeria’s counterterrorism strategy, which also utilizes other measures designed to limit both the supply of potential recruits for the Islamic State as well as the demand for their ideology. On the supply side, one focal point of the Algerian strategy has been to increase its ability to monitor and control the border, especially given the instability that exists in Libya, its neighbor to the east.23 On the demand side, Algeria has sought to employ a whole-of-government approach that includes “prevention and deradicalization.”24 The effort to address extremism in religious spaces and to promote more moderate interpretations of Islam seems to have had, at least in part, the desired effect.25 Despite the seeming success of these efforts, some have criticized the Algerian government’s prevention and deradicalization programs as being little more than an effort to control religious messaging in favor of the regime.26 While an assessment of these claims is beyond the scope of this article, the need to consider how efforts made in pursuit of security may potentially have unintended consequences is a theme in each of the countries featured in this article.

Other Considerations

Interestingly, although Algeria has prioritized its counterterrorism efforts, there are additional factors to consider. Political instability has gripped the country for many years, yet this has not seemed to further increase the willingness of individuals to join groups such as the Islamic State. One explanation for this is that there is also the long history of violence in Algeria, which may have changed the way that Algerians think about all forms of political activism. During the Algerian civil war, the 1990s is known as the “dark decade,” during which an estimated 150,000 people lost their lives.27 During the beginning days of the Arab Spring, the scar of past political violence was one reason some used to explain Algeria’s more limited response.28 Another expert has referenced this same period as a potential reason for AQIM’s struggles in Algeria.29 Thus, it may be the combination of the country’s history with extremism and counterterrorism activity that help explain why it has not seen as much domestic support for Islamic State and why fewer foreign fighters came from within its borders than that of its neighbors.30

Islamic State in the Caucasus

Brief Summary

The Caucasus region, which includes Chechnya, Dagestan, and Ingushetia, has long been the focal point of intense conflicts between a variety of groups. Fighters from the region appeared among early recruits to groups in the Syrian civil war, including the Islamic State.31 Perhaps the most prominent was former member of the Georgian military Abu Omar al-Shishani, who rose in the Islamic State hierarchy to become a top leader in the war ministry.32 By late 2014, the popularity of the Islamic State made it an attractive banner under which fighters in the Caucasus region could unite, eventually resulting in the declaration of an Islamic State province several months later.33 The group’s first attack came shortly thereafter in September 2015 against Russian military forces.34 The violence continued, with the affiliate launching approximately 30 operations between 2015-2020 and carrying out its last reported operation in December 2020.35

Reflections on Current Status

The current status of the Islamic State’s affiliate in the Caucasus is unclear. The affiliate was not mentioned in the 2023 U.S. State Department report on terrorism in Russia.36 The Caucasus region was mentioned in the most recent U.N. report on Islamic State activity around the world, but only in the context of providing fighters to the Islamic State’s affiliate in Khorasan, known as ISK.37 Despite this lack of officially claimed activity, Russian security services have continued to arrest individuals in the North Caucasus, though the official narrative is more that they have links to “banned” terrorist groups, but does not name the actual group or motivating ideology.38 In others, it deliberately misattributes the ideological connection, even though connections to Islamist groups seem apparent to other analysts.b Taken together with what appears to be an encroachment of ISK on the same territory, it makes it hard to say what the status of the Caucasus affiliate is (see more discussion on this topic below in the “Other Considerations” section). Regardless of whether the affiliate itself is active (and not claiming credit), the attacks are being carried out with the support of ISK, or these attacks are inspired by the group’s ideology, it does seem to be the case that violence inspired by jihadism is not a thing of the past in the region.

Counterterrorism Activities

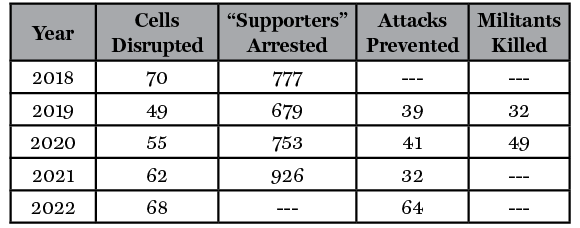

The Russian approach to dealing with this affiliate, at least according to its own reporting, includes a mix of approaches to both kill and detain terrorists, as well as efforts to seek to undermine support for terrorism. When it comes to operations that breakup terrorist cells or otherwise disrupt terrorist plots, Russia reported a decent amount of counterterrorism activity from 2018-2022, as seen in Table 2. Data for later periods is not available, but this data is still useful in the context of this affiliate because it overlaps with the time during which the affiliate’s self-reported operational activities declined and then stopped altogether.

Table 2: Russian Counterterrorism Activities, 2018-2022

Source: U.S. State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism; Media Reporting

Any interpretation of these figures requires a fair amount of caution, in part because they are provided by the Russian government and hard to independently verify. One additional complication is that, at least in 2021, there appears to have been a distinct change in the nature of the Russia governments reports, shifting from focusing on arrests of those associated with jihadi groups to those more connected to Ukraine. Indeed, beyond 2021, media reporting suggested that a surge of “terrorism-related criminal cases” occurred in 2024, although some of the description suggests these arrests might be related to Ukraine, not necessarily to an Islamic State-affiliated group.39 Another cautionary note is that these figures are for all of Russia, not just the territory covered by the Islamic State’s affiliate in the Caucasus.c Still, these figures do show consistent activity and some measure of success in disrupting terrorist plots in Russia prior to 2021, a time in which there was a concerted effort by Russia to deal with the growing threat posed by the Islamic State. The fact that there may have been a shift in Russian reporting of these figures in 2021, which is around the time that the Caucasus affiliate seems to have gone silent, may just be a coincidence.

Additionally, even though there were no claims of responsibility in Al Naba for the Caucasus affiliate’s operations after 2020, media reporting indicated that dozens of Islamist-related arrests were still being carried out by Russia in the Caucasus region from 2021 until as late as August 2024.40 Unfortunately, in many of these cases, the specific affiliation of those arrested is unknown, making it impossible to say if these were affiliate members, inspired sympathizers, or potentially part of another Islamic State affiliate that has taken over responsibility for this region. Regardless, this information does indicate that utilizing law enforcement has been and continues to be the primary counterterrorism method for the Russian government in the Caucasus.

On the side of preventing or countering extremism, reports include efforts aimed at extremism in general, including outreach to religiously oriented educational facilities, designed in part to control of the nature of the religious messages.41 Various reports also indicate that Russia is proactively seeking to prevent and remove what it deems to be extremist or terrorist propaganda online and pass anti-terrorism legislation, although these types of programs and authorities are not only used against Islamic State-affiliated forces.42 Yet, the root causes appear to remain. When the Islamic State first established a presence in the Caucasus region, several analysts pointed out that lack of opportunities, including for youth, led to support for militancy in general, but also for the Islamic State specifically.43

Other Considerations

One challenge in trying to identify the decline of the Islamic State’s Caucasus affiliate is that, in the time since its last reported operation in 2020, ISK has carried out or attempted to carry out operations in Russia, the most prominent of which was the concert hall attack in Moscow in 2024 that resulted in at least 130 deaths.44 This is territory that might have previously been seen as pertaining to the Caucasus affiliate, but there has been encroachment by ISK into the North Caucasus region as well.d Additionally, the July 2025 United Nations monitoring report on the Islamic State noted that ISK “continued to recruit both inside and outside Afghanistan, including among Central Asian States and the Russian North Caucasus” (emphasis added).45 Taken together, these pieces of evidence suggest that ISK may be operating in territory that previously would have pertained to the Islamic State’s Caucasus affiliate. However, it is unknown whether ISK subsumed the Caucasus affiliate and is now using the same infrastructure and members as the Caucasus group or if the Caucasus group has been disbanded and the area has been taken over by the Khorasan affiliate. To further complicate matters, a recording allegedly from members of the Islamic State’s affiliate in the Caucasus emerged in April 2024, encouraging others to take up the cause of the group.46 This raises the possibility that, at least for several years after the final operation of the Islamic State’s Caucasus affiliate, it either remained a separate entity or the group wanted give the perception that it remained a separate entity.

Islamic State in Saudi Arabia (Hijaz and Najd)

Brief Summary

Given its geographic proximity to ground zero of the Islamic State, the fact that a large number of Saudis traveled to Iraq and Syria to fight for the group, and the fact that it has always had to deal with radical elements, it is not surprising that the Islamic State sought to establish itself in Saudi Arabia.47 Eventually, the Islamic State would have two affiliates in Saudi Arabia, Hijaz and Najd, which will be discussed together in this section. The Islamic State accepted Najd into the fold in November 2014, and by May 2015, it claimed responsibility for its first attack, a suicide bombing at a Shiite mosque.48 The Hijaz province announced itself a few months later in August 2015 when it claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing at a mosque that resulted in the death of more than a dozen security services personnel who were worshipping there.49 After this point, the attack tempo of the affiliates remained relatively high for a year or so, but it soon started to change both quantitatively, with attacks decreasing, and also qualitatively, as operations seemed to result more from lone or inspired actors as opposed to a concerted effort by the affiliate itself. The last attributed attack came in November 2020, when the Saudi Arabian affiliate claimed responsibility for a bombing at a World War I commemoration event in Jeddah.50

Reflections on Current Status

Since that last attributed attack, there has been little public information about the current status of the Saudi Arabian affiliate. The 2023 U.S. State Department report on terrorism did not mention the affiliate is having any activity or presence.51 The affiliate is similarly absent from the July 2025 U.N. report.52 And whereas other affiliates released renewed pledges of allegiance in support of newly minted Islamic State caliphs, this did not appear to be the case from the Saudi Arabian affiliate.e This lack of reporting of any sort stands in stark contrast to many of the other repressed affiliates discussed in this article, suggesting that Saudi Arabia has either effectively stamped the group out or that it maintains a very tight level of control on news regarding its existence and activity.

Counterterrorism Activities

In considering the decline and disappearance of the Islamic State affiliate’s formal operations in Saudi Arabia, one of the most important factors to point out is the persistence and efforts of the Saudi counterterrorism services in detecting, arresting, and prosecuting those suspected of participating in or otherwise supporting the affiliate’s activities. For example, in 2014, the government publicized the arrest of 431 individuals affiliated with the Islamic State in a series of operations across the country.53 Two years later in 2016, security services reported arresting 1,390 for terrorism ties, including at least 190 with connections to the Islamic State.54 In 2019, a major attack was prevented when security services shot and killed four attackers targeting a government building, with subsequent operations resulting in the arrest of another 13 suspects.55

But Saudi Arabia’s approach to dealing with the Islamic State, and terrorism in general, is more than just law enforcement action. As one scholar noted, it has sought to approach the non-kinetic fight by targeting the terrorism lifecycle through efforts focused on prevention, rehabilitation, and minimizing the risk of recidivism.56 Though the efficacy of these programs is debated and their use in the case of captured Islamic State supporters is less well known, at the very least they represent a substantial investment in efforts to prevent and counter violent extremism.57 These individually focused efforts have been supplemented by larger initiatives to fight terrorist ideology such as the Global Center for Combating Extremist Ideology and the Ideological War Center, both based in Saudi Arabia and which engage in the broader “war of ideas” by creating counter-messaging as well as flagging terrorist content for removal from online spaces, among other efforts.58 The fight against the Islamic State’s ideology has also been the focus of a targeted effort by government and religious leaders to denounce the group.59 Taken together with the government’s approach to identifying and arresting the affiliate’s supporters, the overall effort seems to have been effective at repressing the operational activities of the group.

Other Considerations

While Saudi Arabian efforts to counter the Islamic State’s local affiliate appear to play a primary role, there may also be a unique dynamic at play that explains the lack of support for the Islamic State’s local affiliate. The idea of a lack of support may seem surprising at first, especially given that an estimated 3,200 Saudi citizens traveled to Iraq and Syria to fight with the Islamic State.60 This is one of the larger country contingents to have traveled, suggesting no shortage of support for the Islamic State. However, scholars have noted that Saudi Arabian support for jihad is unique in that it is most prominently manifested in distant fighting, not actions on the homefront.61

Islamic State in India

Brief Summary

Al Naba featured the first claim of an operation attributed to an India province of the Islamic State in May 2019.62 Any persistent existence of the group, however, has been denied by the Indian government in repeated statements, noting that while there may be some sympathy toward the group, it does not have deep roots.63 While there may be reason to view such denials cautiously, the fact remains that, at least through the group’s own reporting, the India affiliate carried out only 17 attacks from May 2019 to July 2022. The last public communication from the group itself came in December 7, 2022, in which members of the India province of the group pledged allegiance to the Islamic State’s new leader, Abu al-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi.64 Overall, the lack of directly connected activity could be an indication that the Indian affiliate of the Islamic State is struggling, but it might also indicate that the activity simply has changed form, as is discussed a bit more below.

Reflections on Current Status

Relatively little has come out from official Islamic State channels regarding the current status of the Islamic State’s affiliate in India. Given that it has been more than three years since a claimed attack, it might be tempting to write the group off as having collapsed or having never existed. However, in March 2024, the Indian government announced the arrest of Haris Farooqi, claiming that he was the head of the Islamic State in India.65 Still, outside of specific activity officially claimed by the Islamic State or an affiliate, there does appear to be a sizable amount of activity by, at the very least, supporters or sympathizers of the Islamic State. There have been approximately 44 arrests of individuals suspected to be connected in some form with the Islamic State generally, but nothing in either Indian government or Islamic State channels has tied these individuals directly to the Indian affiliate.66 Thus, though the affiliate itself appears dormant, the underlying support for the ideology is not. As has been the case in other affiliates above, this lack of official communication from the Islamic State about the affiliate, combined with continued arrest and other activity, makes it hard to determine the status of the affiliate itself.

Counterterrorism Activities

Perhaps a more compelling reason is a very proactive effort by the Indian government to monitor and arrest those who express support for the group. According to the U.S. State Department, in 2020, India reported investigating 34 cases and arresting 160 suspects related to the Islamic State.67 In 2021, India reported investigating 37 cases and conducting 168 arrests.68 Finally, in 2023, the government reported investigating 21 cases and making 65 arrests.69 Although formal reporting by the U.S. State Department has not been released since 2023, very recent indications suggest that such operations are ongoing. In September 2025, the Indian government reported arresting a cell of five Islamic State supporters in various cities who had been planning to carry out attacks, having gone so far to obtain suicide vests and other weapons.70 Another arrest occurred in October 2025, in which an IED plot by two individuals suspected of having links to the Islamic State was said to be in “advanced stages.”71 As noted above, these arrests are part of about 44 arrests that have taken place since the last claimed operation of the India affiliate in the summer of 2022.

While potentially undercutting the narrative of no foothold for the group in India, the tempo of law enforcement activity suggests two things. First, the Indian government is making a vigorous effort to identify and intervene in cases where the Islamic State may be attracting adherents. Law enforcement action still seems to be the primary pillar of the government’s response, supported by a vigorous effort to collect intelligence on individuals and cells operating in India. This is not to say that the government does not engage in counter violence extremism and deradicalization efforts. Indeed, legislative action to address financing of terrorism as well as increased efforts to engage in content moderation are also part of its approach.72 Second, the fact that arrests are still occurring suggests that the Islamic State’s ideology, if not its affiliate in the region, is still successfully attracting adherents who, whether alone or as part of an organized group, are trying to take actions in the name of the group. While some of the arrests that have taken place since the summer of 2022 are for lone individuals, about half of them are for two or more individuals, suggesting there are still small collectives willing sympathetic to the Islamic State. It is worth mentioning, however, that there did not appear to be any connection to a larger Islamic State in India organization in the open-source information related to these arrests.

Other Considerations

As discussed above, there has been a number of arrests of individuals for support of and participation in cells affiliated with the Islamic State since the last Al Naba claims of operations. The fact that these recent arrests have not been formally tied to the group’s main local affiliate, Islamic State in India, is perplexing. At least according to one scholar, Indian Muslims have generally found a place within the political process, lessening the need to participate in violent jihadi groups.73 The general proposition that democracy might serve as an antidote to terrorism by providing alternate avenues for expressing dissent has found much less support in academic research.74 Moreover, the pace of arrests and plots do not seem to indicate a lack of support for the Islamic State or for violence. A lack of support for this latter fact is also demonstrated by threats from numerous militant organizations other than the Islamic State that India faces, which indicates that there is some willingness on the part of individuals to carry out acts of violence in favor of political ideologies in the country.f

If the Islamic State in India’s seeming disappearance cannot be attributed to a lack of willingness to engage in violence, perhaps another explanation is the group’s activities have simply been redirected under the banner of a different affiliate. As was discussed above in the case of the Caucasus affiliate, the ISK affiliate has increased in prominence over the past few years. It is also proximate to India and could feasibly have taken over operations from the defunct or ineffective India affiliate. There is limited evidence to support this. Of the arrests the Indian government has carried out since the India affiliate’s claims stopped, a small number specifically mentioned an ISK nexus to the suspects. In some cases, it was merely that the individual supported ISK and wanted to travel to its territory. In one case in western India in 2023, an individual was accused of leading an ISK cell in the region with the goal of facilitating transit to Afghanistan.75 In 2025 in the same region, Indian security services arrested a man who was allegedly manufacturing ricin in order to poison local water supplies at the behest of an ISK handler based outside of India.76 While these few actions do suggest that ISK plays a role in some of the cases in India, the open-source evidence since the summer of 2022 is not conclusive in showing that ISK has taken over the group’s India portfolio. If anything, it raises the possibility that India’s law enforcement pressure may have resulted in a more decentralized approach on the part of the group’s supporters, with some sporadic connection to handlers abroad. It also suggests that there may be different Islamic State affiliate networks, with different levels or channels of support, active in the country. Though these networks may not operate under the official label of the group, it seems clear that support for the group’s ideology has not been repressed, even if the affiliate itself appears to have been.

Islamic State in Libya

Brief Summary

The power vacuum present in Libya following the ouster of longtime dictator Muammar Gaddafi has been a boon to the Islamic State, which emerged in separate provinces in the country beginning in 2014.77 In August 2015, Islamic State fighters in Libya established enough control over the city of Sirte that they were able to quell a subsequent rebellion and continue to implement their brutal form of governance.78 This control lasted for approximately a year, until a coalition of local forces supported by Western airpower was able to eject the group from control of the city. Unfortunately, the group remained resilient, carrying out operations within Libya at an increased pace for the next couple of years, before ultimately slowing down in the summer of 2019.79 The Islamic State Libyan affiliate carried out a handful of attacks over the next few years, until April 2022, when the last attack recorded in Al Naba took place. The last formal mention of the affiliate by an official channel of the Islamic State appears to have come in December 2022, when an officially branded photo of a small number of the affiliate’s fighters appeared in support of the Islamic State’s new caliph.80

Reflections on Current Status

Relatively little is known about the current status of this Libyan affiliate. Although the group has not carried out claimed attacks over the past several years, there are indications that it still exists as an organization. For example, in January 2024, Libyan security forces announced that they had arrested an individual they claimed was the leader of the Islamic State in Libya.81 More recently, news reports in August 2025 indicated that Libyan security services had broken up three cells responsible for assisting in fundraising, smuggling, and recruiting for the Islamic State.g In September 2025, an editorial titled “Libya the Glorious” appeared in Al Naba and called on the group’s fighters and supporters in Libya to rise up and return to the fight, whether as a group or individually.82 Whether this call was a reference to an actual planned resurgence or a plea for future relevance is unclear, although in the months since it was issued, there does not appear to have been any additional activity.

Counterterrorism Activities

Libya presents an interesting case for counterterrorism efforts, in large measure because its governance structure has been fractured or in disarray during almost the entirety of the time that the Islamic State has been operating in the country. Today, control of the country remains split between the Government of National Stability (GNS), located in the eastern part of the country, and the Government of National Unity (GNU), located more to the west in Tripoli. This fractured governmental structure has led a number of analysts to suggest that the group will be able to recover from its setbacks.83 However, despite this division, recent assessments have suggested that the Islamic State has been unable to regain much control or momentum, as noted in the 2021, 2022, and 2023 reports on terrorism in Libya by the U.S. State Department.84 However, as noted above, the July 2025 U.N. report on the Islamic State more generally noted that Libyan intelligence services had managed to identify and disrupt three facilitation cells in Libya that were helping funnel people and resources in and out of Libya.85 This suggests that the threat, even though diminished, has certainly not disappeared completely.

As far as identifying potential sources to attribute the overall success against Islamic State elements in Libya, one would need to attribute some credit to the GNS and GNU forces, which have shown themselves to be willing in some cases to go after Islamic State members. However, there has also been a consistent involvement from the international coalition, led mainly by the United States, in initial and subsequent efforts to push back the gains made by the Libyan affiliate, especially in Sirte, during which as many as 500 airstrikes were carried out during the 2025-2016 effort to push back and dislodge the group from the city.86 And, when the group began to resurge in 2018 after seemingly being on the decline for a few years, U.S. airstrikes carried out in 2019 allegedly killed a third of the affiliate’s personnel.87 U.S. security cooperation efforts have continued through to the present day, including in a demonstrative visit of a U.S. warship to key Libyan ports, during which the U.S. embassy noted that it had “increased engagement with Libyan partners across all regions of the country.”88

Other Considerations

When explaining the repressed nature of the Libyan affiliate beyond just counterterrorism, one analyst has pointed to the group’s own missteps, including the brutal way it governed and then lost Sirte, which created a stigma that made it hard for other militant groups in Libya to ally with it.89 The stories of brutality from during the Libyan affiliate’s control over Sirte do present a poor case for jihadis. A 2016 report by a human rights organization documented executions, shortages of medical supplies and food, and restrictions on public life.90 While these stories may have played a role in weakening demand for the group, the 2019 resurgence showed that deeper issues and fractures within Libyan society could potentially give the group room to reemerge.91

Thus, in terms of longer-term challenges that may have inhibited counterterrorism and could do so in the future, it is critical to recall the fractured nature of the Libyan government. As noted, there was some belief that the divided nature of the Libyan government would provide an opportunity for the Islamic State to regroup and reengage in violence. At least at this point, although the group has not been totally eliminated, a reemergence has not happened. While a revival of the affiliate in terms of its operational activity may still come to pass, it also seems possible that the counterterrorism efforts of the divided parties in Libya have been enough to prevent the Islamic State from reengaging.h It also appears that the United States has been supporting the efforts of both parties, even while encouraging a political reconciliation, as evidenced by the decision to hold an annual special operations military exercise in Libya in 2026 in an effort to further “Libyan efforts to unify their military institutions.”92 Of course, the United States is not the only foreign power involved in Libya, as recent years have seen a buildup of Russian forces there.93 Thus, the delicate balance between divided Libya parties has more than just counterterrorism implications. However, efforts by external actors to influence that balance may have counterterrorism consequences for better or for worse and is an issue that should be monitored moving forward.

Islamic State in Sinai

Brief Summary

Among all of the affiliates of the Islamic State, there are few that have achieved the notoriety and managed to maintain a high operational tempo like its affiliate in the Sinai Peninsula. Perhaps that is, in part, because it came into being as an already functioning group, Jama‘at Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis (JABM). The head of JABM responded to the Islamic State’s global call for allegiance, pledging it on November 10, 2014, and having their pledge accepted just a few days later.94 Within a year, the Islamic State in Sinai claimed responsibility for downing a Russian airliner, killing the 224 passengers onboard.95 While the attack against the airplane was certainly one of the group’s higher profile attacks, it was able to carry out numerous other operations, with the U.S. intelligence community crediting the group with 500 attacks in the eight-year period between 2014-2022, including assaults that left anywhere from dozens to hundreds dead.96 Despite this high operational tempo, by the end of 2022, the number of operations being reported on the part of the Sinai affiliate in Al Naba was experiencing a slowdown, with the last operation being recorded in early 2023.

Reflections on Current Status

The 2023 State Department report on the status of terrorism in Egypt noted that the Islamic State’s affiliate was “significantly degraded.”97 In its most recent report in July 2025, the United Nations noted that the group was “not active” but had very little else to say about its size or future prospects.98 Interestingly, the Israeli military carried out an airstrike in Gaza in August 2025 that allegedly killed a member of the Islamic State in Gaza who was responsible for operations in several locations, including the Sinai Peninsula.99 The Egyptian government denied that the individual killed was part of any formal Islamic State organization, but if it were true, the fact that an individual in the Gaza Strip had been responsible for operations in the Sinai Peninsula might suggest some level of reduced capability in theater.100 These scattered sources aside, reporting on the group’s activities, if any, is difficult to obtain given that the government seems to be restricting press access to and reporting from the area.101 Recognizing this caveat regarding the lack of media reporting from the region, there is, at least at the current time, very little public indication of this affiliate’s ability to reemerge or even of what its current activities may be.

Counterterrorism Activities

There can be a tendency to credit a military intervention with success against Islamic State – Sinai, but this would appear to be an inaccurate reading of the facts. According to one expert, despite deploying over 40,000 troops and employing something akin to a scorched earth policy through most of 2018, little headway was being made against the group and its operational tempo continued mostly unabated.102 But, around 2017-2018, Egypt shifted from relying mainly own its own armed forces to cooperating more with local tribes and militias, who were also bearing the brunt of the group’s militant activity.103 These efforts did not yield immediate success, with some analysts pointing out that the government’s approach had, at best, resulted in containment of the group and, at worst, furthered the conditions that would lead to more conflict in the future.104 Despite these concerns, by early 2023 the Egyptian government declared victory against terrorism in the region, with President Abdel-Fattah Al-Sisi stating that “if the terrorists had been able to overcome us, they would have slaughtered us, but we were able to vanquish them.”105 In short, it appears that the effort to involve local tribes in the process of defeating Islamic State – Sinai was in part responsible for the success in the end, at least in reducing the levels of violence perpetrated by the group.106

While the military efforts were the predominant focus, there were also reports of other aspects to the counterinsurgency campaign. For example, in its 2022 report on Egyptian counterterrorism efforts, the U.S. State Department noted that the government had implemented CVE initiatives, including efforts to counter Islamic State propaganda, as well as spending $224 million dollars to compensate residents for damage caused by counterterrorism efforts.107 In addition to this, there have also been reports that one of the strategies used to lure fighters away from the Islamic State were offers of amnesty, although there is a lack of clarity on the terms of these agreements.108 As with most non-kinetic counterterrorism efforts, however, there appears to be little analysis of the effectiveness of these policies.

Other Considerations

Even though the above discussion suggests that the use of the military instrument in tandem with local partners has brought some success, the effort to deal with Islamic State – Sinai is not without complications that may ultimately have implications for the future of the Islamic State and other militant actors in Egypt. More specifically, the campaign against the Islamic State’s Sinai affiliate has brought serious allegations of human rights abuses by the Egyptian military, suggesting the campaign may have hidden costs not fully acknowledged or appreciated yet.109 While there are no indications that such tactics have brought about a backlash or created additional support for the Islamic State at this point, Egypt’s own history with jihadism suggests that it is important to be deliberate in ensuring that military power to counter extremists is employed in tandem with efforts that target both the ideas of jihadis and the motivating factors that draw individuals to their cause.110

Islamic State in Yemen

Brief Summary

Although the Islamic State in Yemen was part of the early group of affiliates recognized by Islamic State Central and started off with some fanfare in November 2014, one scholar noted that it “failed to gain significant traction” and began to decline by 2016.111 Despite this, the group managed to rebound in 2018 and, according to its own reporting in Al Naba, carried out 174 operations between the summer of 2018 and its last recorded attack in the summer of 2022. Even though claimed attacks stopped after that point, this was not the final communication. As is the case with many other affiliates, the last official communications from the group came in the form of pledges of support for newly minted leaders of the Islamic State, one in December 2022 and another in August 2023.112

Reflections on Current Status

Despite the lack of attack activity, the recent July 2025 U.N. report noted that the group had about 100 fighters and focused mainly on “recruitment and facilitation efforts coordinated with ISIL affiliates.”113 Beyond this report, additional details about recent activities by or against the Islamic State’s Yemeni affiliate were not easy to find, leaving the U.N. report as one of the only sources available. However, the fact that little information could be found, including any additional efforts by foreign governments to target Islamic State in Yemen, is suggestive of the fact that, while the group may not have failed, it is also not functioning in the way that it used to. Thus, it does seem repressed, even if it is not defeated.

Counterterrorism Activities

The Yemeni government, for many years before the civil war, relied heavily on the United States for counterterrorism support in the form of financial aid, military weapons, and kinetic strikes against groups such as al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).114 Though most of the United States’ effort was directed against AQAP, in some cases the United States also carried out airstrikes against Islamic State targets, as it did in 2017.115 These efforts were very limited and were conducted as the Yemen government was collapsing due to the economic and political pressures it could not overcome.116 Thus, although the United States was involved in Yemen, to give it or the Yemeni government most of the credit for reducing the operational pace of Islamic State Yemen in the country would be inaccurate.

The lack of strong governmental counterterrorism efforts shifts the focus to the role played by other actors in Islamic State – Yemen’s decline. Indeed, another factor worth taking into account are the Islamic State’s interactions with other militant groups in the area, notably AQAP and the Houthis. When it comes to AQAP’s interactions with the Islamic State affiliate, after some period of time during which the two groups mostly ignored each other, the fighting turned vicious. For example, in 2019, facing increased fighting, part of al-Qa`ida’s Yemeni network offered a $20,000 reward for the head of the leader of the Islamic State affiliate.117 But, while the combat against AQAP likely weakened the Islamic State in Yemen, it seems probable that the Houthis dealt a significant blow to the group in a 2020 counterterrorism operation that resulted in an unknown number of dead Islamic State fighters.118

Other Considerations

Of course, the country of Yemen is in the midst of a civil war between the Houthis and the internationally recognized government.119 This conflict has also attracted considerable attention from third-party states seeking to impact the outcome. It seems entirely probable that this dynamic has impacted the ability of militant groups to organize and operate. As noted by one expert, Yemen has been the battleground for global powers, leading to the possibility that the Yemeni affiliate’s fighters, if not its broader agenda and mission, have been co-opted or otherwise distracted by the challenges posed by the current environment.120 What could happen to groups such as the Islamic State’s Yemen affiliate when the civil war terminates is unclear, but depending on which entity is in charge, it could either find itself with breathing room and a new lease on life, or the target of a government seeking to assert its authority over the country.

A View of the Forest

The small snippets of each Islamic State affiliate above have attempted to present some of the factors that could potentially be credited for the decline in their operational activity. Any such exercise, in which a large number of examples are covered in a limited amount of space, will inevitably miss nuance and detail. Indeed, just as the familiar refrain in the radicalization literature is that each individual’s case is unique, it is likely the case that the outcome of a specific Islamic State affiliate is the result of factors unique to its situation. While such nuance matters and should not be set aside casually, the author attempts to conclude this article by identifying common threads, as well as differences, running through each of these cases.i

The Decline of Islamic State Central. For many of the affiliates that struggled, it seems clear that the diminished capacity of the Islamic State’s main body in Iraq and Syria furthered undermined their own groups. This appears to have been only in part due to decreases in tangible resources such as financial transfers, which in some cases still came to some of the affiliates through regional bureaucratic entities that the Islamic State created to manage its group of affiliates.121 The mere fact that ISC had to create additional entities to help manage the affiliates also suggests a decreased ability to provide as much oversight and input into the affiliates as it had previously.122 But, there also appears to have been something of a reputational hit to the group that may have also impacted the ability of affiliates to continue attracting people to the cause. The damage to the affiliate from the central group’s military defeat likely compounded this issue.

This explanation for the struggles of some of the affiliates is, however, incomplete at best. All of the affiliates, those that were successful and those that failed, had to deal with a world in which their parent organization, ISC, no longer possessed the advantages that made it seem like such a powerful force in mid-2014. Yet, for reasons that are not entirely clear, it seems that the Islamic State’s territorial defeats in Iraq and Syria constituted a stress test that some affiliates were able to weather while others folded under the pressure. One possibility to consider is that the stress test resulted in some affiliates being prioritized by ISC while others may have been left to their own devices.j In other words, ISC may have had to engage in prioritization that resulted in reduced resources and potentially even reduced communications with some of its affiliates. If ISC did have to engage in such prioritization, it may provide at least a partial explanation of uneven performance of the group’s affiliates. While this possibility is intriguing, more detailed information than is available in this article would be necessary to make any sort of detailed assessment of how each affiliate responded to and was affected by the turning of the tides against ISC.

The Rise of Powerful Affiliates. At the same time, while ISC has declined over the past several years, a few of its affiliates appear to have taken on new roles in ways that impact other affiliates. For example, ISK has become one of the more prolific and seemingly well-resourced of the group’s affiliates.123 Given that it operates in proximity to the base of operations for both Islamic State – Caucasus and Islamic State – India, the possibility exists that it may have taken over operations in those areas. At the very least, it does seem that ISK has overshadowed those other entities. In the open source, it is difficult to determine whether the affiliates in this region ceased and then ISK moved in or whether ISK moved in and took over these affiliates, or whether it has simply buttressed their seemingly fledgling operational capability. Nonetheless, there does appear to be evidence in the case of ISK that it has seen its own area of responsibility grow in ways that may have implications for some of the affiliates that formerly existed in those areas.

A Potential Deemphasis of Formal Affiliates. One possibility that is raised by the above analysis is that, either due to counterterrorism pressure or other strategic decisions made by the group, the formal affiliates themselves are simply not as important in the operational or propaganda strategy of the Islamic State in today’s environment. For example, the case of the Islamic State in India, in which sizable number of arrests of individuals associated with the Islamic State have occurred, despite no official statements from the affiliate, might suggest that the Islamic State’s overall approach to the Indian theater of operations has changed. If that is the case, whether that was an intentional decision by ISC for strategic or practical reasons (or some mix of both) is unclear. It may be the case that the Islamic State, in some theaters, has seen the deemphasis of affiliates as a smart move to mitigate counterterrorism pressure while continuing operations. It could also be the case that the affiliate structure no longer exists and the group has simply adjusted to that reality. The question of how the Islamic State is adapting in these spaces where “repressed” affiliates exist is an important question for both practitioners and researchers moving forward.

A Diverse Approach to Counterterrorism Partnerships. When considering the different ways in which hard power was brought to bear on some of the Islamic State’s affiliates in these cases, one thing that seems clear is that there was much diversity in the actors applying that power and how they related to others. An array of counterterrorism partnerships appears to have factored into the decline of the Islamic State affiliates covered in this article. In some cases, it is an international coalition; in others, a single nation. In some cases, it is local government forces or tribal elements; in others, competing militant organizations. While it does appear that hard power, either from above in the form of airstrikes or from across the field of battle in the form of guns, is an important part of the story in the decline of some of these affiliates. However, though “hard power” has forms of value, it would be a mistake to argue that this pressure bears much similarity across these cases. In many of these cases, the nature of counterterrorism military cooperation had to be, of necessity, flexible to the realities on the ground. This led to a diverse set of partnerships, which might not have been chosen as ideal arrangements by military planners beforehand. Yet, the ability to adapt to the context-specific requirements and constraints allows military power to still be applied in an effort to weaken the affiliates.

The Value of Holistic Counterterrorism Strategies. Although some declines may be attributed, either in whole or in part, to concerted military or policing actions, in other cases it seems that the decline itself, or at least the durability of the decline, may also be related to the implementation of strategies that sought in other ways to undermine the Islamic State’s appeal to the local populations. These include programs designed to encourage amnesty in order to provide fighters with a pathway to exit, economic development in high-risk areas, efforts to undermine and identify weaknesses in Islamic State propaganda, and so forth.124 Moreover, even as it applies to the use of hard power, there was considerable variation in how nations facing the threat of Islamic State affiliates deployed their security services in pursuit of these groups. In the case of the Egyptian government’s fight against the Islamic State’s affiliate in Sinai, there was a considerable amount of effort dedicated toward partnering with local tribes and security forces. In fact, one interpretation of what ultimately led to success was this more comprehensive security effort as opposed to a unilateral approach by the national military alone.

The Hidden Costs of Repressed Affiliates. One of the things that stands out from some of the above discussion is that the use of hard power and limitations on some liberties may be a factor to consider in the repression of the operational activity of some affiliates. For example, in one case from 2017, a human rights organization expressed concern that pursuit of the Islamic State’s Yemen affiliate by counterterrorism forces may have involved the use of torture.125 In another case spanning the length of Egypt’s campaign in the Sinai, allegations of extrajudicial killings and mass graves have emerged.126 Whether in the case of Egypt, Libya, Russia, or Saudi Arabia, these measures might create second- or third-order effects that could serve to increase demand for terrorism. To put it another way, steps taken in the pursuit of security against these affiliates may result in grievances and frustrations that could serve to increase future security threats, whether on the part of reenergized affiliates or some other militant organization.

‘Defeat’ Remains an Elusive Goal. As noted in numerous places above, despite their claimed attack activity having diminished to essentially nil (at least according to the Islamic State’s own reporting), very few, if any, of these Islamic State affiliates appear to have been destroyed to the point that they have no members and no longer pose a threat. As is the case in most open-source work, there is often a lack of granular detail regarding the true capabilities and threat posed by clandestine terrorist groups. As noted above, this is made even more complicated by the fact that terrorist groups have demonstrated the ability to “evolve and adjust their approaches in response to pressure.”127

Indeed, there is evidence that some of the affiliates, though not carrying out claimed attacks, have sought to contribute to the overall Islamic State mission through other logistical or supportive activities, such as helping move people and weapons across borders and fundraising, as was noted above in the case of the Libya affiliate. If this is accurate, then another important consideration for counterterrorism forces comes in how to shift focus in the ‘mopping-up phase’ to dealing with group activities that are less visible on the battlefield and potentially require more intelligence and law enforcement support to address. In countries with at least some capabilities to do those types of operations, such as India and Egypt, there may be a good chance that the remnants of affiliates can be contained if not captured or otherwise disabled. However, for countries such as Libya and Yemen, such fine-grained counterterrorism efforts may be beyond their reach.

As a result, it is important not to consider the mission of defeating these repressed affiliates as having been accomplished. Additionally, it is possible (and potentially even likely) that the factors that would ultimately eliminate the threat posed by the group are different from those that lead to a reduction or pause in its attacks. For example, military power may eliminate the group’s capacity to carry out operations, while de- and counter-radicalization efforts may be necessary to remove the motivational factors that remain on the part of whatever small number of group members remain. As discussed above, some countries appear to have implemented these types of policies, while others have not either due to lack of willingness or capability.

Conclusion

This article has sought to provide brief insight into the cases of “repressed” affiliates of the Islamic State, that is those affiliates which have seen a marked decline in their claimed operations. In doing so, the goal was to identify some of the commonalities and differences in each of these contexts. This analysis should not be seen as an exhaustive treatment of each affiliate, but rather as an attempt to obtain a strategic perspective on the potential lessons that might be drawn from looking at the decline of several affiliates at once. As some of the Islamic State’s affiliates in Africa, notably in West Africa and Mozambique, and the group’s capable affiliate in Afghanistan continue to operate with comparatively more levels of success than those covered in this article, the lessons from this article may provide insight into opportunities and constraints that governments are likely to face in countering them. CTC

Daniel Milton, Ph.D., is a Visiting Professor of Political Science at Brigham Young University. His work focuses on the dynamics of terrorist organizations, counterterrorism policy, and international security. X: @Dr_DMilton

Substantive Notes

[a] Al Naba has continued to be released since August 2025, but the data collection for this article stopped at that point in time. However, it was felt that the 12-month window was a defensible, if arbitrary, cut-off point that provided a long amount of time in which an affiliate that was not “repressed” could feasibly plan and carry out another operation. The author wishes to thank Muhammad al-`Ubaydi for conducting and sharing the data collection. As with many projects, they would not have been possible without his diligent work.

[b] The June 2024 attacks that killed more than 25 in Dagestan are an excellent example, as they demonstrate that there are likely incentives for the Russian government to (1) downplay the threat of the Islamic State to avoid looking weak or incompetent and (2) to hype up the threat from Ukraine. In this particular case, the Russian government claimed Ukraine was responsible, but others suggested the attack has Islamist ties. Henri Astier and Laura Gozzi, “Twenty dead in attacks on churches and synagogue in southern Russia,” BBC, June 24, 2024. Some analysts even attributed this attack to the Caucasus affiliate, though only ISK seemed to acknowledge the attack as having been carried out by “brothers in the Caucasus.” “Russian region of Dagestan holds a day of mourning after attacks kill 20 people, officials say,” Associated Press, June 24, 2024.

[c] Another concern with these numbers is the fact that they likely include actions against individuals/groups that Russia defines as extremist, but that would likely not qualify on a more objective standard.

[d] On April 10, 2019, the Caucasus province claimed responsibility for a bombing at an apartment building about 70 miles outside of Moscow. Aaron Y. Zelin, “Attack on Apartment Building in Kolomna, Russia,” Islamic State Select Worldwide Activity Interactive Map, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, April 10, 2019.

[e] The author reviewed each of the post-November 2020 activities in Saudi Arabia as captured by the Washington Institute’s Islamic State Worldwide Activity Map and found nothing in terms of arrests, plots, or operations, whether connected to the affiliate or otherwise.

[f] Data from the South Asia Terrorism Portal indicates that the number of terrorism incidents, though down from its peak of 4,483 events in 2003, is still relatively high with 1,921 events as of November 3, 2025. See https://www.satp.org/datasheet-terrorist-attack/incidents-data/india. India also ranks number 14th in the world in the 2024 annual report of the risk of terrorism produced by the Institute for Economics & Peace. See https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index.

[g] It seems likely that these media reports refer to the same activities that appeared in the July 2025 U.N. report on Islamic State activities, indicating that these arrests likely took place well before August 2025. “Thirty-sixth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011), and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 24, 2025, p. 11; Dario Cristiani, “Weakened Islamic State Eyes Resurgence in Libya,” Jamestown Foundation, October 22, 2025.

[h] This is not to suggest that there are not legitimate concerns or that a political process should not move forward. It does seem likely that, if there is continued political uncertainty into the future and the underlying challenges of corruption are not addressed, there will be more fertile ground for militant groups, whether affiliated with the Islamic State or something entirely different. Vibhu Mishra, “UN envoy warns Libya’s transition at risk amid stalled political roadmap,” UN News, October 14, 2025.

[i] These commonalities are just that and should not be viewed as causal arguments regarding what leads to the decline of affiliates. To make a stronger argument about what actually leads to affiliate decline would require a comparison between the affiliates whose operations appear to have ended and the affiliates that remain operationally active. Instead, these factors should be viewed as potential explanations worthy of future research and study.

[j] The author wishes to thank Don Rassler for making this observation and suggesting a way to incorporate it here.

Citations

[1] Ahmed S. Hashim, “The Islamic State: From al-Qaeda Affiliate to Caliphate,” Middle East Policy 21:4 (2014): pp. 69-83.

[2] Daniel Milton and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi, “Pledging Bay`a: A Benefit or Burden to the Islamic State?” CTC Sentinel 8:3 (2015): pp. 1-7.

[3] Aaron Y. Zelin, “The Islamic State’s Fourth Bayat Campaign,” Jihadology, August 6, 2023.

[4] Ayodele Oluwafemi, “Report: Over 170 killed during Boko Haram attack of Yobe community,” Cable, September 10, 2024.

[5] Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Lucas Webber, and Riccardo Valle, “From Tajikistan to Moscow and Iran: Mapping the Local and Transnational Threat of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 17:5 (2024): pp. 1-12; Daniel Milton, “Go Big or Stay Home? A Framework for Understanding Terrorist Group Expansion,” CTC Sentinel 17:10 (2024): pp. 43-52; Aaron Zelin, “The Islamic State’s External Operations Are More Than Just ISKP,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, July 26, 2024.

[6] Andrew Engel, “The Islamic State’s Expansion in Libya,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 11, 2015.

[7] Jason Warner and Charlotte Hulme, “The Islamic State in Africa: Estimating Fighter Numbers in Cells Across the Continent,” CTC Sentinel 11:7 (2018): pp. 21-28; Lachlan Wilson and Jason Pack, “The Islamic State’s Revitalization in Libya and its Post-2016 War of Attrition,” CTC Sentinel 12:3 (2019): pp. 22-31.

[8] Aaron Y. Zelin, “Pledge of Allegiance of the Soldiers of the Caliphate in Libya to Abu-Husayn al-Husayni al-Qurashi,” Islamic State Select Worldwide Activity Interactive Map, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 19, 2022.

[9] Gregory Waters and Charlie Winter, “Islamic State Under-Reporting in Central Syria: Misdirection, Misinformation, or Miscommunication?” Middle East Institute, September 2, 2021; Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi and Charlie Winter, “The Islamic State in Dera’a: History and Present Situation,” Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, April 24, 2023; Haid Haid, “Why ISIS doesn’t always publicize its attacks,” Asia Times, July 25, 2023; Aaron Y. Zelin and Devorah Margolin, “The Islamic State’s Shadow Governance in Eastern Syria Since the Fall of Baghuz,” CTC Sentinel 16:9 (2023): pp. 22-29.

[10] Petter Nesser, “Introducing the Jihadi Plots in Europe Dataset (JPED),” Journal of Peace Research 61:2 (2023): pp. 317-329.

[11] “Algeria’s al-Qaeda defectors join IS group,” Al Jazeera, September 14, 2014.

[12] Chris Johnston and Kim Willsher, “French tourist beheaded in Algeria by jihadis linked to Islamic State,” Guardian, September 25, 2014.

[13] Aaron Y. Zelin, “Various Activity Reports,” Islamic State Select Worldwide Activity Interactive Map, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, accessed November 10, 2025; Thomas Joscelyn, “Islamic State claims rare attack in Algeria,” FDD’s Long War Journal, November 21, 2019.

[14] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2023 – Algeria,” U.S. Department of State, December 12, 2024.

[15] “Thirty-sixth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team submitted pursuant to resolutions 1267 (1999), 1989 (2011), and 2253 (2015) concerning Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida and associated individuals and entities,” United Nations Security Council, July 24, 2025, p. 10.

[16] Latifa Ferial Naili, “Algeria : Six Terrorists Eliminated, Nine Support Elements Arrested in One Week,” Al24 News, October 1, 2025; Latifa Ferial Naili, “Algeria: Terrorist Surrenders, Seven Terrorist Supporters Arrested in One Week,” Al24 News, October 15, 2025.

[17] Warner and Hulme, “The Islamic State in Africa;” Geoff D. Porter, “AQIM Pleads for Relevance in Algeria,” CTC Sentinel 12:3 (2019): pp. 32-36.

[18] “Algerian army ‘kills jihadist behind Herve Gourdel beheading,’” BBC, December 23, 2014.

[19] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2015 – Algeria,” U.S. Department of State, June 19, 2015.

[20] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020 – Algeria,” U.S. Department of State, December 16, 2021.

[21] Porter.

[22] Hakim Gherieb, “US-Algeria Cooperation in Transnational Counterterrorism,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, March 27, 2017.

[23] Kal Ben Khalid, “Evolving Approaches in Algerian Security Cooperation,” CTC Sentinel 8:6 (2015): pp. 15-20; Nisan Ahmado, “Algeria Eyes Cross-Border Missions as Fear of Militant Spillover Grows,” Voice of America, November 7, 2020.

[24] Michael Greco, “Algeria’s Strategy to Overcome Regional Terrorism,” National Interest, February 27, 2019.

[25] Abdelillah Bendaoudi, “How Lessons from Algeria Can Shape Iraq,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, August 8, 2018; Lotfi Sour, “From GIA to the Islamic State (IS): De-radicalization as countering violent extremism strategy in Algeria,” Journal of Central and Eastern European African Studies 4:3-4 (2024): pp. 169-195.

[26] How the Islamic State Rose, Fell and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb (Brussels: International Crisis Group, 2017), pp. 27-29.

[27] David B. Ottaway, “Algeria: Bloody Past and Fractious Factions,” Wilson Center, August 27, 2015.

[28] Eleanor Beardsley, “Algeria’s ‘Black Decade’ Still Weighs Heavily,” NPR, April 25, 2011; Djamila Ould Khettab, “The ‘Black Decade’ still weighs heavily on Algeria,” Al Jazeera, November 3, 2015.

[29] Porter.

[30] How the Islamic State Rose, p. 3.

[31] Brian Dodwell, Daniel Milton, and Don Rassler, The Caliphate’s Global Workforce: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Foreign Fighter Paper Trail (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2016).

[32] Olga Oliker, “Myths, Facts, and Mysteries About Foreign Fighters Out of Russia,” CSIS, December 21, 2017.

[33] Elena Pokalova, “The Islamic State Comes to Russia?” War on the Rocks, July 20, 2015.

[34] Nick Sturdee and Mairbek Vatchagaev, “ISIS in the North Caucasus,” New Lines Institute, October 26, 2020.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2023 – Russia,” U.S. Department of State, December 12, 2024.

[37] “Thirty-sixth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” pp. 16-17.

[38] “The FSB of Russia Prevented A Series of Terrorist Crimes in the Republic of Ingushetia,” Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation, August 28, 2024; Elizaveta Chukharova, “Three Ingushetian teenagers suspected of ‘preparing a terrorist act,’” OC Media, March 17, 2025.

[39] Elena Teslova, “Russia says over 120 terrorist crimes, including 64 attacks, thwarted in 2022,” Anadolu Ajansi, December 13, 2022; “Russia Saw 40% Surge in Terrorism Cases in 2024, Top Investigative Body Says,” Moscow Times, February 17, 2025.

[40] Giuliano Bifolchi, “Counter-Terrorism Operations in Ingushetia and Adygea: Recent Developments,” SpecialEurasia, September 2, 2024; Aaron Y. Zelin, “Various Activity Reports,” Islamic State Select Worldwide Activity Interactive Map, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, accessed November 13, 2025.

[41] “Russia Seeks to Quash the North Caucasus Terrorist Threat,” CEPA, June 22, 2022.

[42] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020 – Russia,” U.S. Department of State, December 16, 2021.

[43] Sturdee and Vatchagaev; “IntelBrief: Radicalization and Extremism in Russia’s North Caucasus Region,” Soufan Center, April 12, 2024.

[44] “Russia says it thwarted planned attack on synagogue,” DW, March 7, 2024; Kathleen Magramo and Jerome Taylor, “Russia has seen two major terror attacks in just three months. Here’s what we know,” CNN, June 24, 2024.

[45] “Thirty-sixth report of the Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” pp. 16-17.

[46] Giuliano Bifolchi, “Intelligence Report: The Ingush Jamaat and the Islamic State Wilayat Kavkaz,” SpecialEurasia, April 19, 2024.

[47] Thomas Hegghammer, “Islamist violence and regime stability in Saudi Arabia,” International Affairs 84:4 (2008): pp. 701-715; Dodwell, Milton, and Rassler.