Abstract: The civil war raging between global jihadis is intensifying. Despite the shared ideological commitments and mutual state adversaries of al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, these dueling factions have failed to overcome the challenge of fragmentation under the stress of conflict and territorial retreat. Rather than close ranks, these salafi-jihadis have accelerated their fratricidal wars in West Africa, Yemen, and Afghanistan. They turned their attention away from near and far enemies and instead prioritized fighting the nearest enemy of all—each other. A recent Islamic State documentary, Absolved Before Your Lord, released by its Yemeni branch offers the clearest articulation of the differences that divide these two factions. The Islamic State represents an exclusive, uncompromising, and puritanical vision of jihadism, while al-Qa`ida has rebranded jihadism as an inclusive, pragmatic, and populist pan-Islamist movement. Five fundamental disagreements emerged from the documentary over establishing an ‘Islamic’ state, applying ‘Islamic’ law, rejecting populism, embracing sectarianism, and defending puritanism.

It is no secret that salafi-jihadism, the ideology of the deadliest Islamist organizations around the globe, is in a deep crisis. Despite its rapid growth since 2001, salafi-jihadism (henceforth referred to as jihadism) never constituted a single, unified faction.a Instead, its ideologues and organizations often disagree about fundamental issues in the crucible of civil war.1 Two disagreements in particular have become centrifugal, splintering jihadis into opposing camps. The first pertains to the issue of collective takfir—the act of Muslims declaring other Muslims to be infidels—and its byproduct of mass civilian atrocities and sectarian targeting. The second revolves around the importance of establishing ‘Islamic’ states and the application of strict sharia governance within those states, which risk alienating local populations and turning them against jihadis. These two divides constitute a factional dichotomy between puritanism and populism within jihadism.

The Islamic State has embraced puritanical extremism as its defining character. It insists that it constitutes the ‘Victorious Sect’ that uncompromisingly adheres to salafi orthodoxy in doctrine and practice.2 It takes every opportunity to apply ‘Islamic’ law and expunge what it considers ritualistic innovations in its territories; rejects alliances with ‘apostate’ parties or states; and seeks to establish an ‘Islamic’ caliphate without any regard to modern norms of national sovereignty.

This puritanism is juxtaposed with the opportunistic populism of Islamist movements that supposedly tolerate public blasphemy to avoid alienating supporters; delay establishing sharia-based states and instead choose to work within the confines of civil democratic states; and make alliances with secular factions or apostate governments in the name of realpolitik. Jihadis have historically reserved these critiques for Muslim Brotherhood factions and Islamist nationalists like Hamas, but in recent years, the Islamic State has been accusing al-Qa`ida of populist Islamism that seeks to win the hearts and minds of Muslims rather than mold them into believers through the strict application of ‘Islamic’ law.3

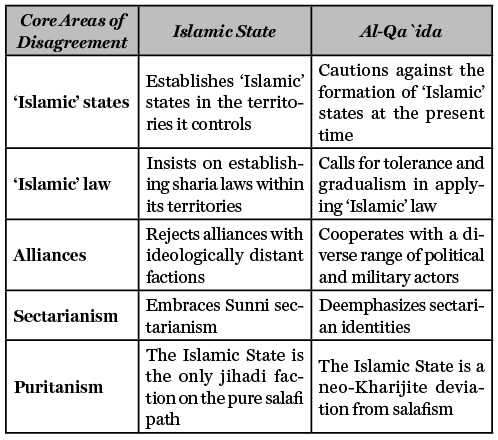

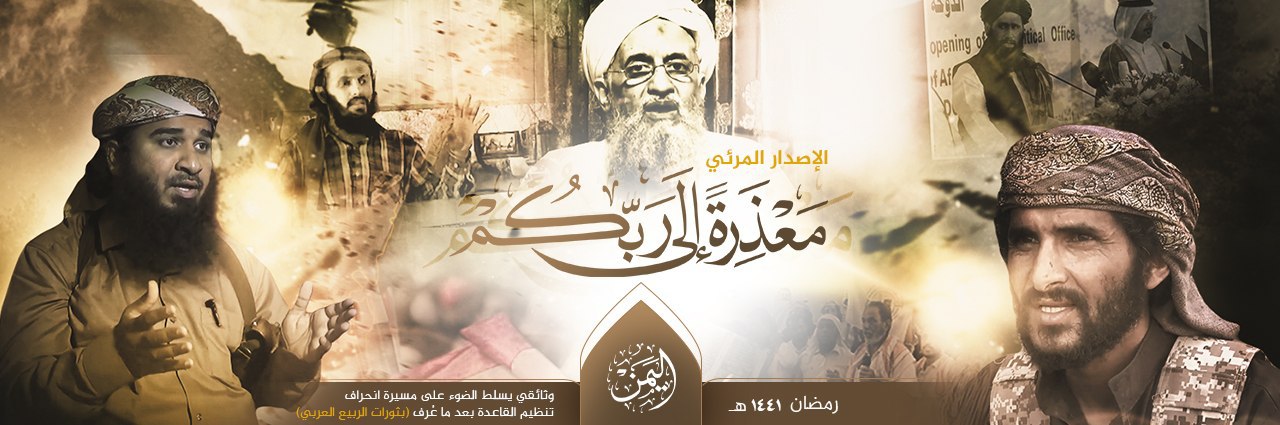

It is in this context that on April 29, 2020, the Islamic State in Yemen, through its Wilayat Yemen Media Bureau, released a 52-minute documentary that spotlights al-Qa`ida’s “journey of deviations after the so-called Arab Spring revolutions.”4 The documentary is titled Absolved before Your Lord (ma‘aziratan ila Rabbikum), a reference to the Qur’anic verse 7:164.b In the documentary, the Islamic State makes five major claims against al-Qa`ida and, in doing so, offers the clearest articulation yet of how the two rivals differ (summary in Table 1).

In the documentary, the Islamic State accuses al-Qa`ida of dithering on the critical issue of erecting an ‘Islamic’ state, a goal that is warranted to “harvest the fruits of jihad” and prevent non-salafis from monopolizing political power. Moreover, it is alleged that al-Qa`ida, out of concern for public opinion, refuses to apply sharia laws within the territories it controls, failing the Qur’anic imperative to “command the good and forbid vice.” Instead, the documentary alleges al-Qa`ida has chosen to chase after the chimera of revolutionary populism, making alliances with apostate factions that embrace democracy, nationalism, and secularism. In this vein, it is alleged al-Qa`ida and its allies refuse to wage war on polytheists, principally Shi`a Muslims, and that they condemn the destruction of Sufi shrines. According to the documentary, to add insult to injury, al-Qa`ida defames the true monotheists of the Islamic State by labeling them Kharijitesc and kills Islamic State soldiers while it refuses to cast aspersions on polytheists, nationalists, and misguided Islamists (for example, the Muslim Brotherhood).

These Islamic State themes are not novel, but they are nonetheless significant for two reasons. First, the author assesses, based on his close tracking of Islamic State statements over the years, that this documentary is the most direct and comprehensive attack on al-Qa`ida and many of its branches to date, encompassing criticism of al-Qa`ida in Syria, Mali, Libya, Afghanistan, and Yemen in one fell swoop. It suggests that Islamic State leadership is doubling down on its branding choice despite the major setbacks it experienced with the demise of its self-proclaimed caliphate in Iraq and Syria and the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. It also reveals that the Islamic State is further consolidating its central authority over its regional commanders in the wilayat (provinces) by diminishing their ability to forge tactical alliances with rival jihadis in conflict theaters. Second, this latest documentary adds credence to earlier CTC Sentinel analysis by Tore Hamming and Hassan Hassan, both of whom highlighted the deep roots of puritanical factionalism within the jihadi movement—predating the official split between these two organizations—and predicting the expansion and endurance of factional strife in the years ahead.5 By claiming exclusive jihadi legitimacy in the April 2020 documentary, the Islamic State’s go-it-alone strategy is intended to preclude calls for factional coexistence with al-Qa`ida. Only time will tell whether this strategy is a mistake on the part of the Islamic State or a decisive blow to its rival’s diminished movement.

This documentary is significant for another reason. It sheds additional light on the ongoing power struggle between the Islamic State in Yemen and al-Qa`ida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) that began in July 2018.6 AQAP is undergoing internal organizational struggles in light of its recent leadership turnover and because of a growing controversy over how best to handle allegations of spying within the organization. On January 29, 2020, AQAP lost its leader, Qasim al-Raymi, to a U.S. drone strike. He was replaced by Khaled Batarfi who now presides over a fragmented and substantially diminished movement due to a protracted civil war with Houthi rebels, continuous U.S. airstrikes on its leadership, and internal conflict over how best to redress its compromised organizational security.7

The Islamic State perceives a window of opportunity to intensify its attack on AQAP, one of the largest and most loyal followers of Ayman al-Zawahiri, the leader of al-Qa`ida. Earlier in 2020, the Islamic State leaked audio of AQAP members urging al-Zawahiri to mediate between AQAP factions over the issue of internal spies and collaborators. One faction has wanted an independent tribunal to adjudicate charges of spying, but this was rejected out of hand by Batarfi because, he maintained, it might reveal critical organizational security measures. The Islamic State also released the names of what it claimed were three executed AQAP members and 18 of its leaders and scholars who resigned their positions or turned themselves over to Saudi authorities.8 The Islamic State has had every intention to add fuel to the rumors that AQAP is infested with spies to hasten defections.

A significant part of the documentary is dedicated to a critique of AQAP. It highlights what it claims is the collaboration between AQAP leaders and the Yemeni government in their joint war on the Houthis, thus offering evidence of al-Qa`ida’s supposed alliances with governments that previously killed jihadis and have no intention of ruling with ‘Islamic’ law. It also claims AQAP refuses to implement ‘Islamic’ rules in areas it controls, which it argues is evidence that al-Qa`ida places its political considerations above the religious imperative to command the good and forbid vice. The documentary further asserts that AQAP turned its territories over to local tribal councils and even socialist party officials rather than seek to install an Islamist government, which it alleges is additional proof that al-Qa`ida is too eager to give away the spoils of jihad to placate popular sentiment. The documentary concludes with testimonies of several AQAP defectors to the Islamic State in Yemen, thus encouraging others to do the same.

In the section that follows, the author offers a theoretical framework by which to analyze infighting among militant organizations that share the same ideological genealogy. Revolutionary movements from the same family tree often disagree about core conflict issues such as who are their adversaries, what are the best strategies to defeat them, and what are legitimate ways to fight them. These disagreements often yield a split between purists and pragmatists, dividing the loyalties of the broader movement between two viable alternatives. Such family feuds can be particularly threatening to militant organizations that draw their recruits and resources from the same constituent pool, resulting in a zero-sum competition between two rival factions. Next, the article illustrates this ideological dynamic by discussing how the Islamic State draws a sharp divide with all other Islamist factions by spotlighting five areas of disagreements with its closest rival, al-Qa`ida. The author concludes by discussing the implications of jihadi fragmentation for countering violent extremism, highlighting both the dangers and opportunities of the ongoing civil war within jihadism.

A Family Feud: Theorizing the al-Qa`ida-Islamic State Schism

It might be surprising to some that two organizations that embrace an identical ideology, jihadism, might clash in the name of that ideology. It is not uncommon, however, for militant organizations with shared ideological origins to compete with each other based on their degree of pragmatism vs. extremism or populism vs. vanguardism.9 d Factional conflicts are not confined to Islamist movements, but instead are part of a historic pattern that includes iconic rivalries such as the May 1937 clashes between Stalinists and Trotskyists during the Spanish Civil War, the Haganah and Revisionist Zionists in Palestine prior to Israel’s independence (1931-1948), the Algerian National Movement and the National Liberation Front during their anti-colonial struggle against France (1954-1962), and the Sri Lankan Tamil Tigers and its four rival Tamil factions in the mid-1980s.

The process of competition between rivals can be threatening to some factions, leading them to consider violent escalation as a response to these new threats. Competition from rivals can lead to political marginalization in the militant movement if one group is outmaneuvered. Competition can also unleash fear of internal defections. Militant leaders could see their fighters or entire brigades abandon them to join their rivals, taking away valuable territory and resources in the process. Competition can also result in betrayal. Militant groups may see their competitors negotiate with the government or switch to the government side.e

Organizational rivals from the same ideological family tree are particularly threatening to one another because they are competing for the same constituency from which they seek recruits, funding, and safe haven. Their ideological proximity to each other due to their common intellectual heritage makes them credible voices to the movement’s fighters, supporters, and sponsors over which they compete. Yet their ideological distance on key conflict issues means that their disagreements can divide their fighters, followers, and sponsors between two viable alternatives. This proximity-distance paradox threatens to produce defections from one’s group to a rival faction and, if unchecked, can result in the marginalization of one faction in a zero-sum competition. Thus, kindred movements—as in the case of al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State—can turn to bitter enemies despite their mutual intellectual origins and shared utopian vision.

Specifically, the Islamic State-al-Qa`ida split can be analyzed along three ideological dimensions: conflict framing, conflict objectives, and conflict targeting. Conflict framing refers to how a faction constructs a shared understanding of the conflict in which it is an active participant. It answers the basic question: who are we fighting against? The classic debate among jihadis has been whether to prioritize their near enemies (local regimes) or far enemies (Western states).10 Al-Qa`ida, under the leadership of Usama bin Ladin, answered with the latter. However, the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the subsequent rise of powerful Shi`a movements and governments led some jihadis to revert back to emphasizing threats stemming from domestic regimes and their local auxiliaries. The rise of the Islamic State of Iraq in 2006 refocused jihadism on prioritizing attacks against the near enemy, emphasizing the sectarian nature of the new Iraqi polity as opposed to the U.S. occupation of the country.f

This reprioritization of the near enemy above the far enemy was an important source of tension between al-Qa`ida’s leadership in Pakistan and its affiliate in Iraq, but did not result in a complete organizational schism at the time.11 The strategic gulf widened further during the outbreak of Arab Spring revolutions that substantially weakened the repressive apparatuses of several authoritarian regimes. Jihadis appeared better positioned than ever to take advantage of state weakness to topple domestic governments and establish Islamist states in their stead.12 The rise of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) was a step in that direction, but al-Qa`ida resisted the siren call of the Islamic State and advocated for strategic patience. It framed Arab revolutions as a transition phase that requires cross-coalition mobilization to ensure that entrenched political elites are removed from power and hostile states are not provided a pretext to intervene on behalf of the ancien régime.13

Conflict objectives answers the question: what are we fighting for? Ideologically proximate groups could still disagree about the nature of the polity they seek to establish and the scope and pace of revolutionary change, as well as its territorial limits. Both al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State aspire to a sharia-based polity in which ‘Islamic’ law reigns supreme and in which, from their perspective, ‘Islamic’ authorities, from the Sunni tradition, are given their proper place in the judiciary. Al-Qa`ida, having drawn costly lessons from failed jihads, has advocated for gradualism in implementing its vision of an ‘Islamic’ order. Al Qa`ida has argued that there is little to be gained in establishing states that make glaring targets for foreign powers, or marching toward ‘Islamic’ governance without the support of the masses. The Islamic State, however, asserted its prerogative to carve out territory for Sunnis and establish states that rule with ‘Islamic’ law; anything short of that would, from their point of view, violate God’s imperative to command the good and prohibit vice. The Islamic State declared a territorial caliphate without regard to other militant groups, including Islamists and salafis, that did not wish to break up their territorial states along sectarian divides nor rule them with strict sharia law.

Conflict targeting answers the question: who can we legitimately attack? While targeting is usually a tactical or strategic issue, it can be ideological if certain categories of people are deemed to be irredeemable enemies by the mere fact that they represent a detested out-group.14 Al-Qa`ida, true to its novel strategy of fighting the ‘far enemy’ and increasingly sensitive to the criticism that it kills fellow coreligionists, has in recent years sought to minimize sectarian targeting and its associated practice of collectively anathematizing (takfir) non-Sunni communities.g The Islamic State, conversely, insisted that it was both a religious obligation and a public good to target Shi`a communities and Sufi shrines to purge the earth of what the group views as their misguidance.

Thus, despite their shared normative commitments and mutual state adversaries, al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State have failed to overcome the challenge of factionalism that tore asunder many other ideological movements. The stress of conflict and the urgency for survival did little to bind them into a singular unified movement. In fact, beginning in 2013, they descended into fratricidal violence in multiple conflict zones, starting in Syria and extending to Libya, Yemen, and Afghanistan. For a period of time, the one exception was the relatively cooperative relationship between the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) and the al-Qa`ida affiliate Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), both in the West African Sahel region. However, even there this mutually understanding between rivals, built on common origins, personal connections, and common enemies, broke down in the summer of 2019. Since July of that year, at least 300 jihadis have perished in factional wars between the ISGS and JNIM.15

The Nearest Enemy: The Islamic State Rebukes al-Qa`ida

The Islamic State’s recent barrage of verbal salvos aimed at al-Qa`ida comes in the midst of protracted factional wars between their affiliated groups on several jihadi fronts, extending from the North and West African Sahel regions, Libya, and Somalia to Yemen, Syria, and Afghanistan.16 The Islamic State’s aforementioned April 2020 documentary, Absolved before Your Lord, draws attention to these conflicts and frames them as a sharp divide between puritanism and populism. It brands the Islamic State as exclusively committed to the pure salafi creed, regardless of the cost and consequences, and presents al-Qa`ida as having deviated from the salafi way in pursuit of false revolutionary slogans and mass public support.

Establishing an ‘Islamic’ State and Applying ‘Islamic’ Law

The first two themes of the Islamic State documentary are closely integrated together. The Islamic State accuses al-Qa`ida of refusing to take up what it believes is the historic responsibility of establishing ‘Islamic’ states in territories it controls and applying ‘Islamic’ law within those states. Instead, it is claimed that al-Qa`ida has surrendered the “fruits of jihad” to ersatz Islamists who abide by notions of civil democratic states or, equally unacceptably, to popular committees composed of a mix of Islamists, secular nationalists, socialists, and tribal figures. For the Islamic State, these are forces of blasphemy and apostasy that will never permit the application of ‘Islamic’ law. As the documentary puts it, “they replaced one tyrant with another, and have substituted polytheists with others who are even more blasphemous toward God.” According to the documentary, al-Qa`ida foolishly anticipates cooperation from these factions, but sooner or later, it will “reap the bitter harvest” of betrayal.h These allies will turn their guns on the jihadis as they have already demonstrated in Iraq, Syria, Mali, Libya, Egypt, and Sudan. Worse still, it asserts, al-Qa`ida excuses its blasphemy in the name of tolerance and gradualism, all while it derides the true monotheists (i.e., Islamic State members) and fights them at every juncture.

The debate over establishing ‘Islamic’ states is not new, to be sure. Jihadis have disagreed about when and where to establish ‘Islamic’ states in Algeria, Iraq, and Syria in the last three decades. Although they all share the ambition of reviving an ‘Islamic’ caliphate that unites the ummah (Muslim nation) across borders, not all see this goal as immediately attainable. Therefore, they disagree about the strategic priorities necessary to achieve this long-term objective.

From the broad corpus of jihadi thought, it is possible to discern three separate views on the issue of a territorial state. The first view comes from al-Qa`ida, which holds that establishing ‘Islamic’ states is not a priority under the present circumstances; indeed, it is counterproductive. Precedence should be given to supporting revolutions against entrenched regimes and depriving counterrevolutionary elites from exploiting the jihadi bogeyman to undermine popular support for these revolutions. Al-Qa`ida believes they should seize these opportunities to establish their organizational presence—even if through indirect front organizations—and offer their support and experience in consolidating revolutionary turnover.17 This strategy involves stepping back from the demand of establishing an ‘Islamic’ state and making tactical alliances with local revolutionaries, sidestepping some of their ideological differences, and refraining from controversial policies that might alienate local populations, including sectarian killings, demolishing Sufi shrines, or governing with strict sharia codes.

The second view comes from local jihadis mired in civil wars. These include the Taliban in Afghanistan and Ahrar al-Sham in Syria, to give just two examples. These groups are fighting to topple their regimes in order to establish ‘Islamic’ states within the framework of the modern nation-state. Their territorial vision is confined to their existing borders; they are not interested in abrogating their states’ territorial integrity. Thus, they generally refrain from talking about an ‘Islamic’ caliphate that promises to upend the Westphalian system of sovereign states.

The third view comes from the Islamic State. It harbors the irredentist ambition of restoring an ‘Islamic’ caliphate over territories that were divided by Western powers after the First World War (the so-called Sykes-Picot borders). The Islamic State cares little about state sovereignty, the complex political considerations of local Islamist factions, or the interests of external powers. Whereas al-Qa`ida and other Islamists seek to work hand-in-hand with their beleaguered populations in order to win their hearts and minds, the Islamic State cares little about populism and instead advances an exclusive, vanguardist vision that seeks to mold hearts and minds through the divine imperative to command the good and forbid vice.18 As a result, it seizes every opportunity to carve out a territorial state from within and across sovereign state boundaries and governs with a strict sharia code without regard to local customs and religious sensitivities.

Rejecting Unholy Alliances

According to the April 2020 Islamic State documentary, al-Qa`ida has forged unholy alliances with parties that either do not adhere to the strictures of salafism or that clearly exploit local and transnational jihadis without ever intending to advance their Islamist projects. The documentary spotlights al-Qa`ida’s alliance with the “heathenistic” Taliban despite its “clear deviations and apostasy.”i The Taliban is faulted for having, according to the Islamic State, deep ties to the “apostate” Pakistani intelligence services and for recognizing the Islamic Republic of Iran and its borders. The Taliban is also criticized for negotiating a peace deal with the United States in alleged exchange for it fighting the Islamic State.

In Syria, the Islamic State’s documentary points out that Jabhat al-Nusra, before it ever distanced itself from al-Qa`ida, had direct alliances with factions sponsored by Gulf states and Turkey, a NATO member. This cooperation, according to the documentary, does not augur well for establishing genuine ‘Islamic’ governance in the region. Similarly, in Yemen, the documentary underscores what it alleges is the direct and intimate cooperation between AQAP commanders and Yemeni government forces fighting against the Houthis under a Saudi-led coalition. These are presented as strange bedfellows more likely to result in betrayal, not an ‘Islamic’ order.

The documentary also derides Ayman al-Zawahiri as “the nation’s laughingstock” (saafih al-umma) after he, according to the Islamic State’s telling of events, exhibited respect for the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt before it was toppled in 2013 and appeared sympathetic to the plight of its deposed leader Mohammed Morsi. According to the Islamic State, al-Zawahiri imparted legitimacy on a faction it labels al-ikhwan al-murtadin (the Apostate Brotherhood), one that “harbors under its Islamic patina the jahili (pagan) doctrines of nationalism, patriotism, and democracy.”

Embracing Sectarianism

The Islamic State is unapologetically sectarian, viewing as its mission the annihilation of the Shi`a sect and the destruction of Sufi symbols of heresy. It rationalizes this genocidal violence under the theological aegis of collective takfir. In the April 2020 documentary, the Islamic State scolds al-Qa`ida for refusing to embrace sectarian targeting because doing so would alienate mass public opinion. It highlights Ayman al-Zawahiri’s prior statements in which he rejects giving priority to fighting Shi`a, excusing them on the basis of their “ignorance” and insisting that the best way to deal with them is by proselytization and socialization, not sectarian conflict. It also chides him for making an ecumenical public outreach to Coptic Christians in Egypt and calling them “our partners in this homeland.”j Lastly, the Islamic State criticizes the Taliban for, in its telling of events, protecting the Hazari Shi`a rather than killing them.k

The killing of coreligionists poses the greatest difficulty for jihadis from an ‘Islamic’ jurisprudential perspective as well as a public relations standpoint. It is no surprise, therefore, that this practice has unleashed intense criticisms by other jihadis who are concerned about the permissibility of this violence and its political repercussions. The practice of takfir, especially the controversy over the collective anathematization of the Shi`a and Sufis, has been a major vulnerability for militant Islamists, one that they have been trying to mitigate through theological nuance. Al-Qa`ida pragmatists have argued that takfir must be confined to individuals subject to strict rules of due process. The Islamic State since its origins with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founder of al-Qa`ida in Iraq, has insisted that collective takfir is permissible since jihadis are in no position to adjudicate apostasy cases individually under present circumstances.19

The Islamic State today asserts that it does not indulge public opinion when it comes to ahkam shar‘iyya (divine judgments). It holds that certain beliefs and practices nullify a person’s status as a Muslim, leaving the pious no option but to label that person an infidel unless she or he returns to the right path. Otherwise, the lives and property of an apostate are no longer sacrosanct and can be expropriated without compunction. This rule, the group believes, applies to the Shi`a and cannot be suspended under the pretext of considering public opinion.

Defending Puritanism

Al-Qa`ida and other jihadis have denounced the Islamic State as modern-day Kharijites, extremists that kill Muslims—even fellow jihadis—simply for failing to give their oath of allegiance (bay`a) to its organization.20 These criticisms have hit a nerve with the Islamic State as evidenced by how much time and effort it gives to rebutting these claims. The Islamic State asserts exclusive jihadi legitimacy; it alone waves the banner of monotheism and defends itself against apostates and hypocrites who have coalesced against it.

According to the April 2020 Islamic State documentary, al-Qa`ida casts aspersions on the puritanical monotheists even as it refrains from uttering one derogatory word toward secularists, Shi`a, Christians, and the Muslim Brotherhood. In the name of strategic advantage, it is alleged to tolerate allies with blasphemous doctrines, no matter how egregious, but refuses to join the Islamic State, which has succeeded in capturing territory and is applying ‘Islamic’ law. The Islamic State documentary alleges al-Qa`ida avoids attacking polytheists (a reference to Sufis and Shi`a) by excusing their ‘ignorance’ while making its top priority fighting and killing the righteous soldiers of the Islamic State.

The Islamic State is adamant in rejecting the neo-Kharijite label and turns the tables on al-Qa`ida by insisting that its leaders after the death of bin Ladin and Anwar al-Awlaki, to name just two, have deviated from the salafi paradigm and compromised on core issues of creed. It argues al-Qa`ida is not fit to lead other Islamists on the battlefield because it will lead them astray. The Islamic State presents itself as exclusively legitimate because it puts jihad in the service of monotheism, not nationalism, democracy, or populism. It insists on establishing an ‘Islamic’ caliphate without regard to modern international norms; it applies ‘Islamic’ law with or without the approval of the masses; and it rejects alliances with non-Muslims in accordance with the principle of wala’ wal bara’ (loyalty to Islam and disavowal of infidels). It will either triumph and reap the fruits of jihad or die honorably advancing its puritanical vision.

Implications

At its point of origins, jihadism represented a clear alternative to prevailing Islamist trends, principally the non-violent activism of the Muslim Brotherhood, the territorial parochialism of Islamic nationalists, and the political quietism of salafi scholars. Adherents of salafi jihadism became the most aggressive proponents of pan-Islamic unity. Yet, paradoxically, jihadis never cohered into a united front. Instead, they became divided by new ideological, strategic, and tactical differences. Consequently, their pan-Islamist movement is once again in tatters.

Specifically, jihadis have diverged on critical issues such as collective takfir (excommunication of Muslims), sectarian targeting, and the importance of a sharia-governed territorial state. These disagreements produced distinct repertoires of violence among their adherents in important conflict zones such as Iraq and Syria. It also led to a violent rupture between al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, two of the most important proponents of pan-Islamist jihadism today, setting in motion intense intra-jihadi conflicts in Libya, Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and most recently West Africa.

Western observers may take comfort in the fact that violent extremists are at each other’s throats, but this would be the wrong implication to draw. Since 9/11, the problem of violent jihadis has grown in scale, scope, and violent magnitude—all this despite being divided and pursued by a super power, multinational coalitions, and local governments. Whereas in the past the international community was dealing with one global jihadi movement headquartered in Afghanistan, today there are two with branches that span several regions and countries. These jihadis have proven their ability to plan operations and fight their adversaries even as they are killing each other.

More ominous is the potential for terrorist outbidding by both of these organizations. It is known from numerous studies that militant organizations facing serious rivals use outbidding strategies to capture a greater share of media coverage, recruits, and financing.21 A faction facing the prospect of marginalization into obscurity might ratchet up violence to exhibit superior commitment to the cause, or it can engage in bold terrorist innovations like al-Qa`ida executed on 9/11 to show greater efficacy than its rivals.22 Thus, intra-factional struggle to consolidate power behind one of two competing visions of transnational jihadism should not be confused with imminent jihadi defeat. Vigilance and well-considered long-term strategies are still necessary to contain and defeat this multipronged threat.

Notwithstanding these dynamics, factional strife does not bode well for jihadi victory. Research shows that united movements are more likely to achieve their objectives than divided ones.23 United movements are better able to harness resources against state adversaries, negotiate with a single voice, and attract external sponsors. Conversely, divided movements waste their resources fighting rivals, are vulnerable to spoilers during negotiations, and appear as lost causes to external sponsors. Factional conflicts also encourage militant defections away from the movement and toward the state, which is what happened in Algeria during the 1990s and in Iraq during the American occupation.24 In recent years, jihadi factional strife encouraged some jihadis to side with non-Islamists in order to balance against their jihadi rivals. Interestingly, the April 2020 Islamic State documentary accuses Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qa`ida’s former affiliate in Syria, of collaborating with secular nationalists to fight the soldiers of the caliphate.

In sum, the crisis within jihadism presents counterextremist forces with opportunities to discredit this movement by highlighting its internal fragmentation and ideological incoherence. It also presents them with openings to diminish movement cohesion and encourage defections to the state. Local tribes and populations caught in the cross-fire of factional rivals can be persuaded to side with the forces of law and order to restore security and stability to their regions. Lastly, in theaters where the defeat of jihadis is not imminently attainable, counterextremist forces could encourage factional rivalries to preclude the consolidation of power behind a united movement and ensure continuous strife among what would otherwise be brothers-in-arms. CTC

Dr. Mohammed M. Hafez is a professor of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California.

© 2020 Mohammed M. Hafez

Substantive Notes

[a] A recent study estimates that adherents of salafi-jihad increased by 270 percent between 2001 and 2018, numbering in 2018 between 100,000 and 230,000. As of 2018, there are at least 67 salafi-jihadi groups worldwide, a 180-percent increase from 2001. See Seth Jones, Charles Vallee, Danika Newlee, Nicholas Harrington, Clayton Sharb, and Hannah Byrne, “The Evolution of the Salafi-Jihadist Threat: Current and Future Challenges from the Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, and Other Groups,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, November 2018, pp. 7-9.

[b] In this verse, believers are asked why they continue to warn those whom God will destroy or punish harshly. They respond, in order “to be absolved [from blame] before your lord and perhaps they may fear Him.” This title self-servingly suggests that the Islamic State has sufficiently warned al-Qa`ida of its errors, and therefore, it is justified in attacking al-Qa`ida’s followers.

[c] Jihadis, including members of the Islamic State, are often accused of being modern day Kharijites (khawarij al-‘asr), a reference to the historically detested sect known for its extremism and violence in Islam’s formative period. Kharijites, those who secede from the community, fought Ali Bin Abi Talib, the fourth of the Rightly Guided caliphs in the Sunni tradition, and eventually assassinated him in 661 C.E. They have earned the reputation of being renegades beyond the pale. Interestingly, Islamic State scholars have accused internal rivals of being Kharijites. See Cole Bunzel, “Ideological Infighting in the Islamic State,” Perspectives on Terrorism 13:1 (2019): pp. 13-22.

[d] Ironically, Ayman al-Zawahiri, before joining al-Qa`ida, disagreed with Egyptian Islamists on the question of populism vs. vanguardism. His rivals in the Egyptian Islamic Group favored a populist social movement approach to revolutionary change, but al-Zawahiri’s Islamic Jihad insisted on a cohesive vanguard military strategy to overthrow the Egyptian regime.

[e] The most instructive example of this side-switching dynamic is what happened to al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI), the predecessor of the Islamic State, in 2006-2008. In that time period, many of its former insurgent and tribal allies defected to the U.S. side under the Sons of Iraq and Tribal Awakening initiatives to drive AQI out of their towns and cities. Carter Malkasian, Illusions of Victory: The Anbar Awakening and the Rise of the Islamic State (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017); Mohammed M. Hafez, “Al-Qa`ida Losing Ground in Iraq,” CTC Sentinel 1:1 (2007). It should be noted that in October 2006, AQI began operating under the name the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI).

[f] Interestingly, a 2009 strategic document by the Islamic State of Iraq framed its targeting policy reorientation with the phrase “nine bullets plus one,” meaning 90 percent of its attacks would target local adversaries while 10 percent would be dedicated to attacking U.S. forces in Iraq. The Arabic document, translated by the author, carries the title “A Strategic Plan to Strengthen the Political Position of the Islamic State of Iraq” and can be found at https://mohammedhafez.academia.edu/research#papers

[g] Al-Zawahiri, for example, issued instructions to his followers to exercise restraint toward “deviant sects” in an audio message titled “General Guidelines for Jihad,” released by al-Sahab Media on September 14, 2013.

[h] This reference to the “bitter harvest” is not incidental. It mocks Ayman al-Zawahiri by alluding to his earlier work of criticism against the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, The Bitter Harvest: Sixty Years of the Muslim Brotherhood. The Arabic book was published in the late 1980s, but the author has the version published in 1999 by the Beirut press Dar al-Bayariq.

[i] The Islamic State uses the Arabic adjective wathaniyya to describe the Taliban, which it casts as idolatrous because of its Hanafi-Maturidi-Deobandi theology that permits Sufism and jurisprudential eclecticism. The term wathaniyya also mocks the Taliban’s nationalist (wataniyya) orientation, which confines its armed struggle to ethnic Pashtuns inside of Afghanistan.

[j] This criticism of al-Zawahiri dates back to 2016. In an audio message released on January 5, 2017, al-Zawahiri rebutted these chargers by clarifying that what he meant by Coptic Christians being “our partners in this homeland” was a mere reference to “agriculture, trade, and money… in accordance with the laws of our sharia.” See “Al-Qaeda Chief Ayman al-Zawahiri Calls ISIS ‘Liars,’” Al Arabiya, January 6, 2017.

[k] This claim by the Islamic State is the most puzzling given the long history of victimization that the Hazaris have endured at the hands of the Taliban while in power and during their nearly two decades of insurgency in Afghanistan. See Bismellah Alizada, “What Peace Means for Afghanistan’s Hazara People,” Al Jazeera, September 18, 2019.

[3] Hassan Abu Hanieh and Mohammad Abu Rumman, The “Islamic State” Organization: The Sunni Crisis and the Struggle of Global Jihadism (Amman, Jordan: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, 2015).

[4] “Absolved before Your Lord,” Islamic State in Yemen, April 29, 2020. The SITE Intelligence Group has a translated version behind its paywall.

[5] Tore Hamming, “The Hardline Stream of Global Jihad: Revisiting the Ideological Origin of the Islamic State,” CTC Sentinel 12:1 (2019); Hassan Hassan, “Two Houses Divided: How Conflict in Syria Shaped the Future of Jihadism,” CTC Sentinel 11:9 (2018).

[7] Gregory D. Johnsen, “Khalid Batarfi and the Future of AQAP,” Lawfare, March 22, 2020.

[8] Mohammed al-Ta‘ani, “What was revealed in AQAP’s communique about the scope of its internal struggles and its missing leaders,” Akhbar al-Alaan (Now News), May 14, 2020 (in Arabic).

[10] Fawaz A. Gerges, The Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[11] Mohammed M. Hafez, “The Origins of Sectarian Terrorism in Iraq,” in Bruce Hoffman and Fernando Reinares, eds. The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat: From 9/11 to Osama bin Laden’s Death (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014), pp. 436-460.

[14] Omar Shahabudin McDoom, “The Psychology of Threat in Intergroup Conflict: Emotions, Rationality, and Opportunity in the Rwandan Genocide,” International Security 37:2 (2012): pp. 119-155; Francisco Gutierrez Sanín and Elisabeth Jean Wood, “Ideology in Civil War: Instrumental adoption and beyond,” Journal of Peace Research 51:2 (2014): p. 217.

[16] Ibid.; Daniel L. Byman and Jennifer R. Williams, “ISIS vs. Al Qaeda: Jihadism’s Global Civil War,” National Interest, February 24, 2015; Caleb Weiss, “Reigniting the Rivalry: The Islamic State in Somalia vs. al-Shabaab,” CTC Sentinel 12:4 (2019): pp. 29-35.

[17] Lister, p. 4.

[19] Mohammed M. Hafez, “Debating Takfir and Muslim-on-Muslim Violence,” in Assaf Moghadam and Brian Fishman eds., Fault Lines in Global Jihad: Organizational, Strategic and Ideological Fissures (Abingdon, United Kingdom: Routledge, 2011), pp. 25-46.

[20] For example Ayman al-Zawahiri, “Caliphate of Oppression,” audio recording released on October 5, 2015.

[21] Mia M. Bloom, “Palestinian Suicide Bombing: Public Support, Market Share, and Outbidding,” Political Science Quarterly 119 (2004): pp. 61-88; Andrew Kydd and Barbara F. Walter, “The Strategies of Terrorism,” International Security 31:1 (2006): pp. 49-79; Adria Lawrence, “Triggering Nationalist Violence: Competition and Conflict in Uprisings against Colonial Rule,” International Security 35:2 (2010): pp. 88-122; Stephen Nemeth, “The Effect of Competition on Terrorist Group Operations,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58:2 (2014): pp. 336-362.

[23] Peter Krause, Rebel Power: Why Nationalist Movements Compete, Fight, and Win (New York: Cornell University Press, 2017).

[24] Paul Staniland, “Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Insurgent Fratricide, Ethnic Defection, and the Rise of Pro-State Paramilitaries,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 56, 1 (2012): 16-40; Mohammed M. Hafez, “The Curse of Cain: Why Fratricidal Jihadis Fail to Learn from Their Mistakes,” CTC Sentinel 10:10 (2017).

Skip to content

Skip to content