Abstract: After expulsion of Islamic State forces from Mosul, Iraq’s government declared the country “fully liberated” and the Islamic State “defeated.” But field interviews and non-threatening psychological experiments with young Sunni Arab men from the Mosul area indicate that the Islamic State may have lost its “caliphate,” but not necessarily the allegiance of supporters of both a Sunni Arab homeland and governance by sharia law. These continued supporters of some Islamic State core values appear more willing to make costly sacrifices for these values than those who value a unified Iraq. Nearly all study participants rejected democracy, and expressed unwillingness to tradeoff values for material gain. Thus, rather than relying on implementation of Western values or material incentives to undercut (re)radicalization, the findings suggest that alternative interpretations of local society’s core values could be leveraged as ‘wedge issues’ to better divide groups such as the Islamic State from supporting populations.

From July to October 2017, the authors conducted in-depth, one-on-one interviews, including evaluation on a series of psychological measures, with young Sunni men just coming out from under Islamic State rule in Mosul, Iraq, and the surrounding region. To a significant degree men like this are likely to shape and be affected by the post Islamic State political and security landscape in the region. The goal was to better understand how people who had lived under the Islamic State perceived: 1) the Islamic State’s rule; 2) the Islamic State’s political and insurrectional prospects following military defeat by the Iraqi Army and allied militia with aid from an international coalition dominated by the United States and Iran; 3) their own political future; and 4) their willingness to make costly sacrifices for their primary reference groups and for political and religious ideals.

The multidisciplinary and multinational team of researchers has been working on the frontlines of the fight against the Islamic State since the beginning of 2015.a In their research with frontline combatants in Iraq (peshmerga, Iraqi Army, Sunni Arab militia, Kurdistan’s Workers’ Party (PKK), and captured Islamic State fighters), the authors employed an initial set of psychological measures to gauge willingness to make costly sacrifices.1 In these frontline studies, whose results the authors’ replicated in more than a dozen online studies among thousands of Western Europeans outside the conflict zone, the authors investigated two key components of a theoretical framework they termed “The Devoted Actor” to better understand people’s willingness to make costly sacrifices.2

The Devoted Actor framework integrates research on “sacred values” that are immune to material tradeoffs—whether religious or secular, as when land or law become holy or hallowed—and “identity fusion,” which gives individuals a visceral feeling of oneness and invulnerability to a primary reference group to which they belong.3 The authors found three crucial factors common to those devoted actors most willing to make costly sacrifices: The first was commitment to non-negotiable sacred values and the groups that the actors are wholly fused with. The second was readiness to forsake kin for those values. And the third was devoted actors’ perception that the spiritual strength of their own group (often interpreted as heartfelt commitment to the group’s values) outweighed their perception of the group’s material strength or that of its enemies (often interpreted in terms of manpower and firepower). The authors showed that, in extreme conflicts, expressed willingness to act in defense of core values can trump cost-benefit calculations, with implications for policy decisions relevant to improving the political and security outlook in a particular region.

More generally, these prior studies, as well as the new results presented here, are part of a series of investigations intended to inform policymakers and the public about recent findings from social science research on the relative importance of material interests versus abstract ideals and values, which can help determine individuals’ willingness to make costly sacrifices in geographic “hot spots.” The research methodology does not involve general attitudinal surveys or form-filling questionnaires. Rather, the authors employ a theoretical framework developed in the course of research in conflict zones around the world, using a series of dynamic measures (described below) to tease out that framework so as to identify pathways to and from individual and collective violence and to better understand potential implications for policy.

To prepare for this post-Islamic State research, the authors elicited policy-relevant questions from the following policymaking groups in order to help provide responses grounded in empirical research with both practical implications and theoretical scope: the U.S. military (active and recently retired), members of the United States Congress, the White House, HMG Daesh Task Force and Stabilisation Unit, France’s Conseil Supérieur de la Formation et de la Recherche Stratégiques, Germany’s Ministry of Defense, European Union leadership in Brussels, the United Nations Security Council’s Counter-Terrorism Committee, and the Arab Barometer. The following general research and policy questions emerged:

What do people coming out from under Islamic State rule think of the Islamic State in the recent past, at present, and in terms of the future?

What do they think of a unified Iraq?

What political future do they want?

What would they tolerate?

What could appeal to them to prevent emergence of a violent successor to the Islamic State?

Following initial piloting of questions and measures with a preliminary sample, a second set of 70 interviews with Sunni Arab men (average age of 23.81, ranging for 18 to 30 years) were carried out in five camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) (Khazer and Debaga camp complexes). Located between Mosul and the Kurdistan region of Iraq, the camps were managed by the Kurdistan Regional Government with the assistance of a variety of international NGOs.b After some time spent with each prospective interviewee (chosen as randomly as feasible while walking through the camps) to acquire informed consent that also ensured anonymity, the authors proceeded to the interview, which lasted on average about two hours and allowed for justifications of responses and other reflections on life under the Islamic State, in the camps, and prospects for the future.

Because in-depth interviews in conflict zones require considerable time (including hours spent daily going to and from the field sites), and are otherwise challenging, samples tend to be much smaller than with standard surveys and questionnaires. For this reason, and to ensure both theoretical and methodological generalizability, the authors have validated all measures with populations in other conflict zones, as well as from entirely different cultural contexts outside of conflict zones.

The results that follow suggest that although the Islamic State has now lost almost all Sunni Arab lands in Iraq, perhaps a considerable segment of the present generation of young Sunni Arabs continues to share with the Islamic State its most sacred value, measured in terms of willingness to make costly sacrifices for it: namely, strict belief in sharia as the only way to salvage and govern society. The individuals sampled tended to describe strict sharia as God’s guarantee of justice and freedom, and the only way to eliminate oppression and corruption. Whereas the Islamic State’s foreign fighters may have truly fought for this, at least in initial perceptions, some interviewees believe that mission was undermined by local Islamic State elements. A majority of participants also believe that the United States, and fully half of the sample believe that Iran, caused or helped the Islamic State to turn against their people, the Sunni Arabs, in order to divide and subjugate them.

The authors found a significant divide between those who support a unified Iraq versus those who simultaneously support both an independent Sunni Arab homeland and sharia rule, with no appreciable support for democracy from either side. The overwhelming majority believes that democracy brings only destruction. Those who support a Sunni Arab homeland and sharia expressed greater willingness to sacrifice for this cause than those who support a unified Iraq.

The implication is that there may be a good portion of young Sunni Arab men in the region that still adhere to some of the Islamic State’s core values—above all, the absolute rule of sharia law.

A possible policy implication emerging from the preliminary results is to focus on failures of the Islamic State and other jihadi groups in the region to live up to basic tenets of sharia as indicated by the authors’ sample of young men. These included the perception that the jihadis had failed to create solidarity among all walks of society, protect guests who do not intend to harm their hosts, and avoid divisions within the Muslim community (fitna) caused by misinterpretations. It also included the sense the Islamic State had misapplied sharia, and failed to prevent civil war within the Muslim community (the data suggest that only fear of civil war could cause people to appreciably relax adherence to their particular interpretation of sharia).

The conclusions and possible policy implications of this study are, of course, tentative given the limited population sample and pending confirmation through further field studies. However, reliable results from even this initial stage of investigation of the post-Islamic State socio-political horizon may help to provide researchers and policymakers some grounding to build upon amid the ongoing turbulence.

The Overarching Narrative

1. Initial Popular Support for the Islamic State “Revolution” (al-Thawra). Most of the participants who had lived under Islamic State rule in the region told the authors that most people among the Sunni Arab population initially welcomed the Islamic State as a glorious “Revolution” (al-Thawra) devoted to implementing Allah’s rule in the form of sharia law to protect the Sunni people. When asked about what people in the community thought was good about the Islamic State, only seven percent (n = 5) answered “nothing.” The great majority (93 percent, n = 65) mentioned the “good” that the Islamic State did, at least at the beginning of its rule, especially with defense, commitment to religion, implementation of sharia, and provision of security, stability, and a sense of freedom (primarily owing to open roads with no checkpoints in Islamic State-ruled areas):c

“There was freedom to move anywhere, no identity cards, no checkpoints,” one young man said of the first months of Islamic State rule. “The Iraqi Army used to humiliate us at checkpoints and take money to let people pass. [The Islamic State] let young people feel freedom. They rebuilt bridges and schools.”d

“But then [the Islamic State] lied,” he went on. “They told everyone that there would be a general amnesty, that there would be no punishment for people who followed sharia. Then they broke their promises. They would dig into people’s past. They killed former army officers and police and anyone with an important position in the [former] government, first terrifying them, then taking money from them, later executing them.”

Others were more inclined to excuse the Islamic State, ascribing its increasingly brutal behavior to the pressure on them from coalition attacks and airstrikes. Some of the interviewees saw a clear difference between the foreign fighters’ dedication to the caliphate and the locals’ lack of commitment. The foreign fighters were much more committed, one young man told one of the authors, because “they believed in the cause; that’s what they came for, and they were willing to die for what they came for. Some walked the streets with [suicide] belts to show they were ready to die.” He also explained that their salaries from the Islamic State were meager compared to what Iraqi Army and peshmerga soldiers receive. In the words of one Kurdish soldier involved in the offensive to retake Mosul, “the muhajireen [foreign volunteers] of Daesh [Islamic State] fight to die.”

The authors even met a number of Sunni Arab militia commanders, currently fighting with the Iraqi Army and peshmerga, who acknowledged initially welcoming the Islamic State. These commanders, often members of tribal elites, only switched sides when the Islamic State turned to class warfare, inciting less privileged tribesmen to seize the elite’s property and kill them (although such seizures required the Islamic State’s permission and were taxed). Many of these dispossessed elites and their kinsmen want blood revenge, adding to the threat from Shi`a militias a dangerous potential for internal conflict among post-Islamic State Sunni Arab communities in Iraq.

Overall, despite an end-state perception of the Islamic State as corrupt, brutal, and hypocritical (see Figure 1), the authors found lingering support and respect for what people thought the Islamic State stood for at the beginning.

Figure 1. Perception of the Islamic State at the end of its rule as fairly corrupt, brutal, and hypocritical. Means were significantly far from the theoretical midpoint of a bipolar scale (perceived closeness to Honesty vs. Corruption, Brutality vs. Kindness, and Sincerity vs. Hypocrisy), t(69), all ps < .001.

Figure 1. Perception of the Islamic State at the end of its rule as fairly corrupt, brutal, and hypocritical. Means were significantly far from the theoretical midpoint of a bipolar scale (perceived closeness to Honesty vs. Corruption, Brutality vs. Kindness, and Sincerity vs. Hypocrisy), t(69), all ps < .001.

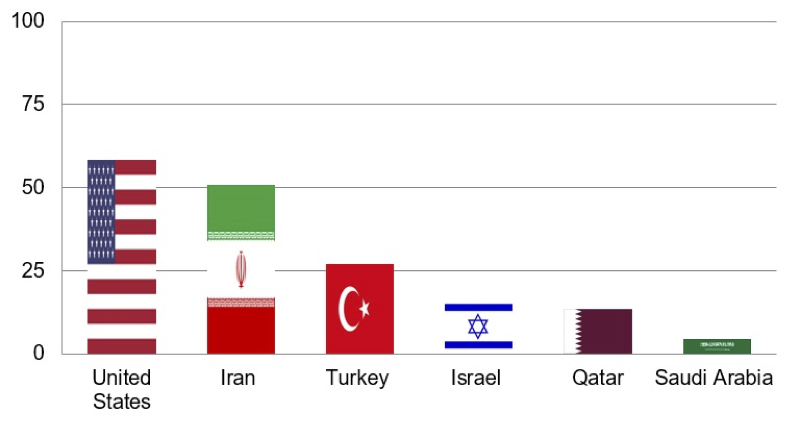

2. The United States and Iran turned the Islamic State to their own advantage, to destroy the Sunni Arabs. A majority of participants believe that two countries, the United States and Iran, helped the Islamic State (see Figure 2). More than one in four believe that Turkey also helped the Islamic State. The most common claim with regard to alleged assistance is that “America helped IS with money and arms.” Other repeated claims include “America created IS” and “America saved IS leadership.” Iran, too, is viewed by some as having created the Islamic State and having sent soldiers to the group “to fight against Sunni and Iraqis.”

For most, Iran (94 percent, n = 6 4) and America (89 percent, n = 62) conspired against Iraq, in general, and Sunnis, in particular, to divide, humiliate, and subjugate them, and even to “eliminate our religion.” Also cited is the notion of U.S. revenge against the Sunni Arabs in particular, and Iraq in general, for the insurgency against U.S. occupation of Iraq after 2004 and for the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. Turkey, a country of mostly Sunni non-Arabs, is viewed as helping the Islamic State in order to bolster its influence with Sunni Arabs and counter the influence of Kurds (also Sunni non-Arabs) by “opening its borders to foreign fighters,” “letting most remaining IS leaders flee to Turkey,” and by “taking care of wounded IS” to fight another day.

Figure 2: Countries perceived to have helped the Islamic State

Figure 2: Countries perceived to have helped the Islamic State

Experimental Measures and their Relationships

Identity Fusion

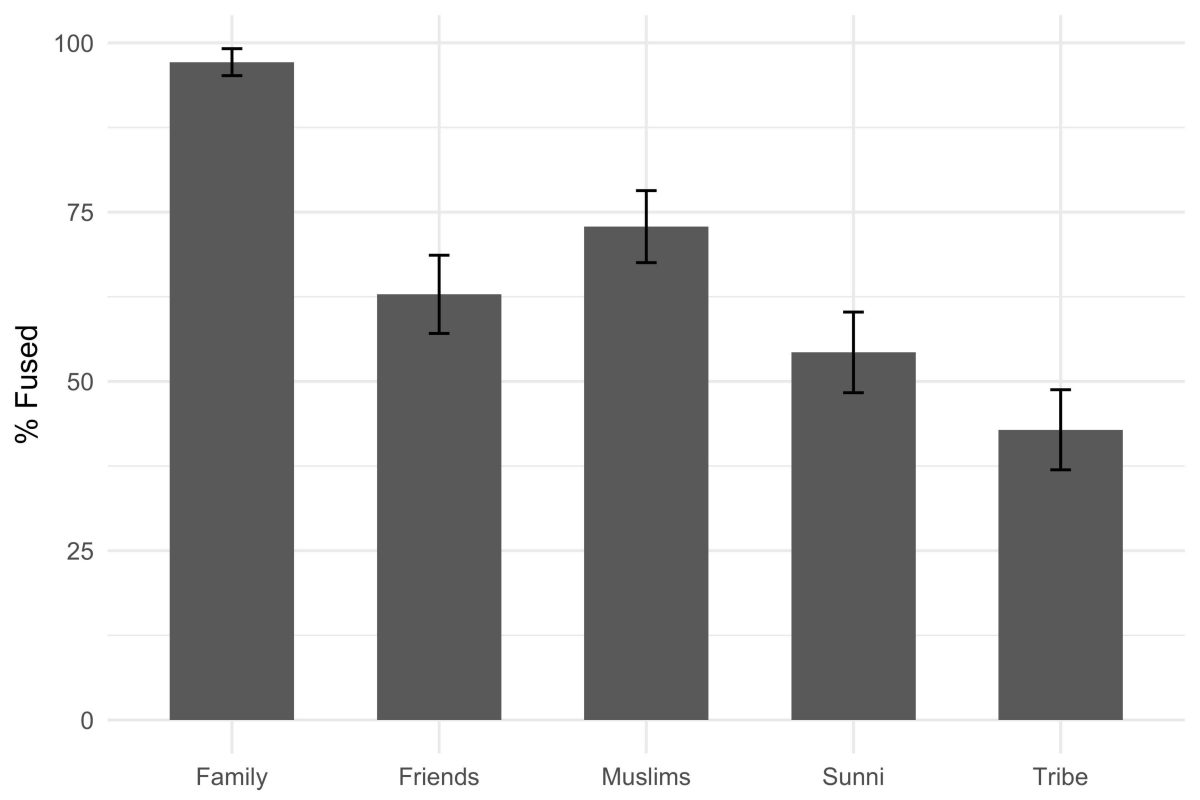

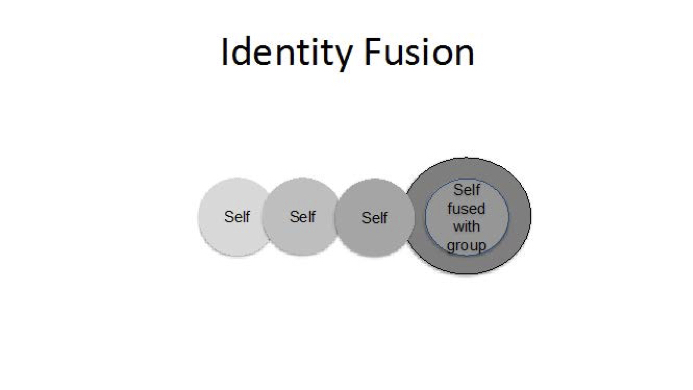

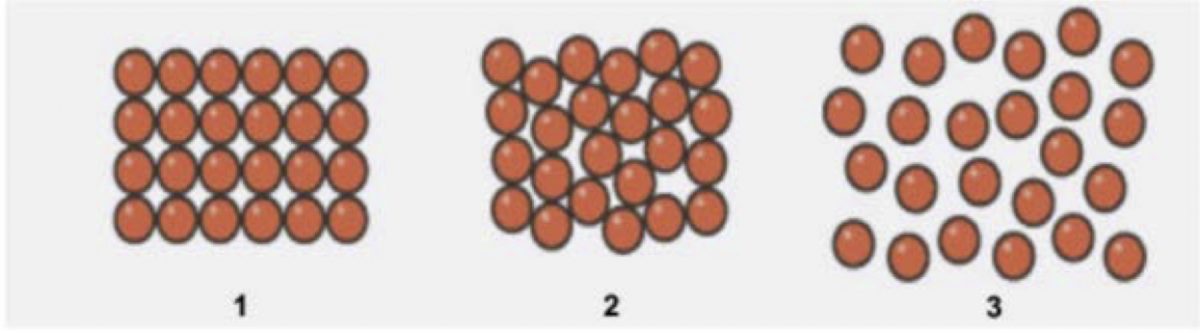

Identity fusion refers to a visceral feeling of connectedness with a group that predicts extreme pro-group behavior and that has been assessed by pictorial, verbal, and dynamic methods. Here, the authors probed identity fusion among the interviewees with family, friends, Muslims generally, Sunni Arabs, and tribe by using a dynamic display on a touchscreen device. Participants were shown a circle representing the self (“me”) and another circle at some distance representing the group of interest, which was displayed using a flag or another identifying pictorial representation. They then could reduce the distance between these circles (up to a complete overlap) to the position best reflecting their relationship with the group (Figure 3). Only people who chose a position where the two circles representing the self and the given group fully overlap are considered fused with the group. (Hence, although the instrument is continuous, the resulting measure is dichotomous, non-fused vs. fused.) Previous experiments in a wide range of cultural contexts and conditions show that people who indicate that their relationship with the group is best reflected by the two circles completely overlapping think and behave in ways different from those who choose any other option:4 they wed their personal identity (“who I am”) to a unique collective identity (“who we are”), perceiving the personal and social identities as a single identity.

Figure 3: Static representation of dynamic identity fusion measure

Figure 3: Static representation of dynamic identity fusion measure

As in other contexts, the authors found that fusion with family is most prevalent. Fusion with the tribe was least common in the sample, and fusion with the Sunni community was positively correlated with fusion with tribe, r = .37, p < .001 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Identity Fusion. Percent of participants fused with family, friends, Muslims generally, Sunni Arabs, and tribe.

Costly Sacrifices

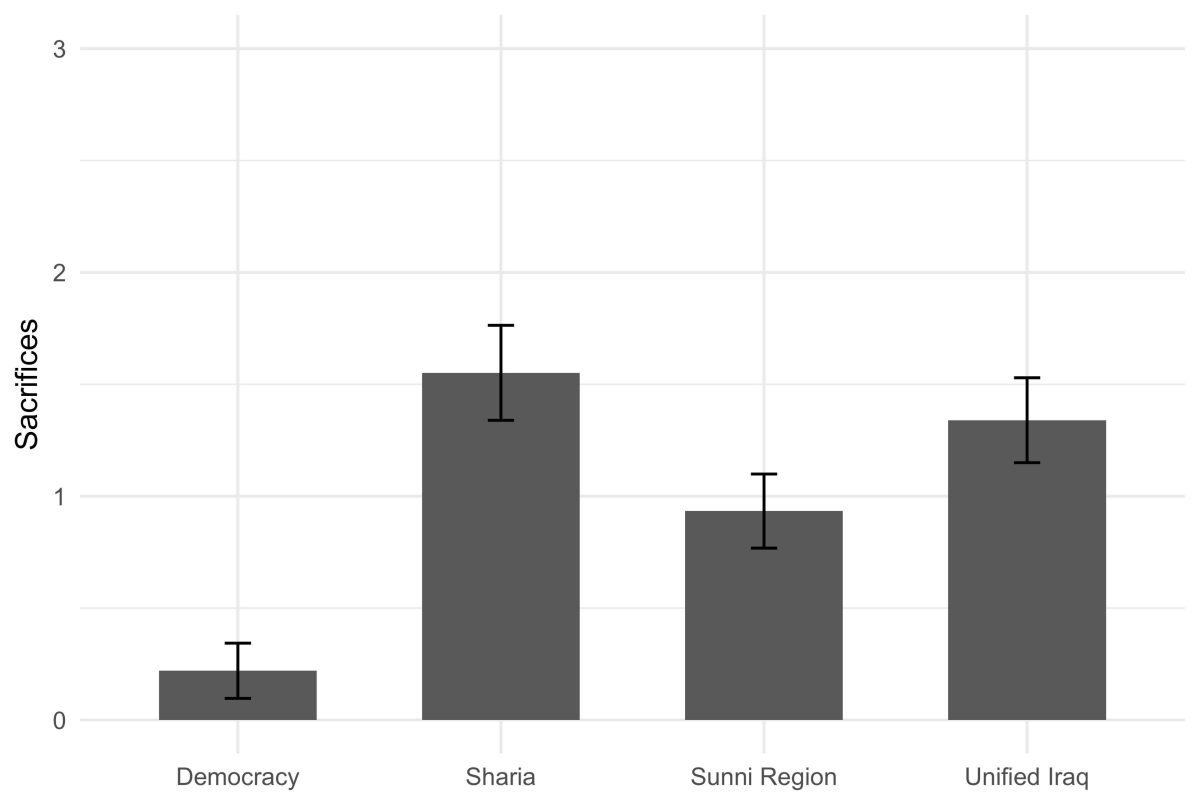

Participants were asked to what extent they would agree with a number of sacrifices in defense of each of four values: democracy, sharia, independent Sunni homeland/region, unified Iraq (Figure 5). The sacrifices were: lose job or source of income to defend the value, go to jail; use violence; die; and let their children suffer physical punishment. People were willing to sacrifice most for sharia and least for democracy.

Figure 5. Willingness to Make Costly Sacrifices for Values: 0 = strongly disagree to 3 = strongly agree. Combined sacrifice set (Cronbach’s alphas .74 to .98, all reliable) included lose job or source of income to defend the value; go to jail; use violence; die; let my children suffer physical punishment).

Figure 5. Willingness to Make Costly Sacrifices for Values: 0 = strongly disagree to 3 = strongly agree. Combined sacrifice set (Cronbach’s alphas .74 to .98, all reliable) included lose job or source of income to defend the value; go to jail; use violence; die; let my children suffer physical punishment).

Tradeoffs

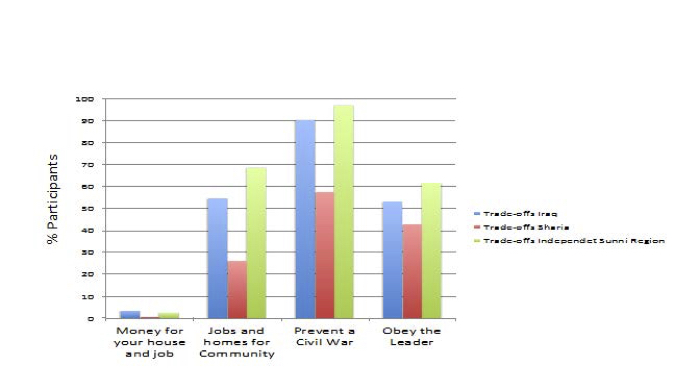

Participants were then asked if they would accept different trade-offs (money for personal housing, or getting a [better] job, homes or jobs for the community, preventing a civil war, obeying their leader) to forsake an independent Iraq, sharia, or an independent Sunni region (Yes/No). Almost no participants would accept money for housing or a job (Figure 6). People are most concerned about avoiding a civil war, although more than 40 percent of participants would not compromise on sharia even to avoid civil war. Obeying the leader, which is more consistent with preference for authoritarian government than democracy, appears as important as providing jobs and homes for the community.

Figure 6. Tradeoffs for Values (independent Iraq, sharia, independent Sunni Arab homeland). Few people were willing to trade off their values for money or personal gain, but significant numbers were willing to trade off their values to prevent civil war (although over 40 percent were unwilling to trade off sharia to this end).

Figure 6. Tradeoffs for Values (independent Iraq, sharia, independent Sunni Arab homeland). Few people were willing to trade off their values for money or personal gain, but significant numbers were willing to trade off their values to prevent civil war (although over 40 percent were unwilling to trade off sharia to this end).

Sacred Values

Sacred values are defined as ideas, preferences, or beliefs that people refuse to measure along material scales, typically evidenced by a refusal to trade them off for economic (e.g., money), social (e.g., status), or other material benefits. Refusal to contemplate the first two of the given tradeoffs was taken as an indicator of a sacred value. The authors then asked participants to choose their most sacred value among sharia, unified Iraq, independent Sunni region, and democracy (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Sacred Values. Percentage of participants who chose the specific value as the most sacred (i.e., unwilling to trade off values or any material advantage) among sharia, unified Iraq, independent Sunni region, and democracy

Figure 7. Sacred Values. Percentage of participants who chose the specific value as the most sacred (i.e., unwilling to trade off values or any material advantage) among sharia, unified Iraq, independent Sunni region, and democracy

Nearly half of participants considered sharia their most sacred value, about one in four considered a unified Iraq, and nearly the same number considered an independent Sunni region to be their core value. Only two people claimed democracy as the most important sacred value. The authors then tested participants’ expressed willingness to make costly sacrifices for their values (again, sharia was most worthy of sacrifice and democracy least).

Perceived Group Cohesion

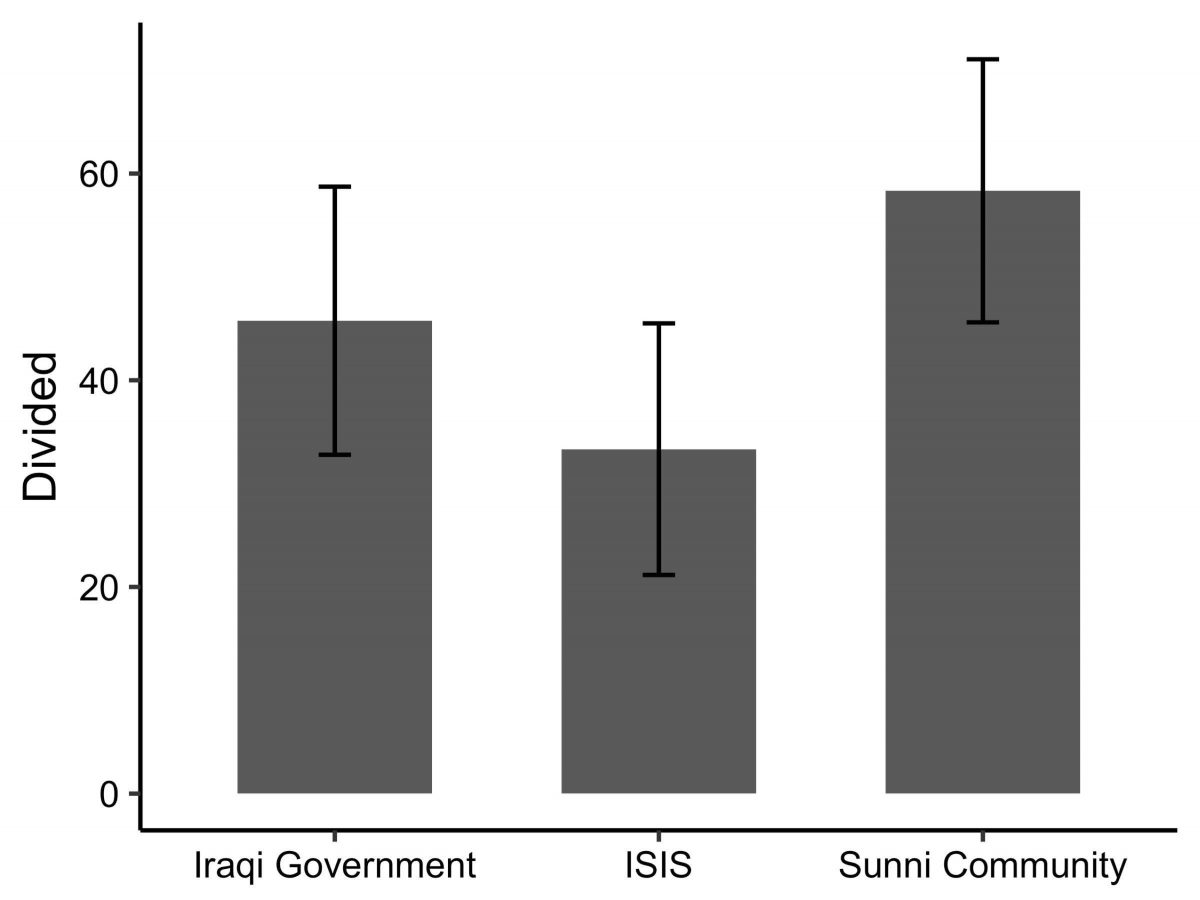

The authors tested a new measure of group cohesion that involved a choice between a loosely packed group of circles (representing group members) separated from one another, a somewhat compact group of circles touching one another, and a highly compact group of circles all stacked together in a regimented manner (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Measures of Group Cohesion: 1 = Strong, 2 = Moderate, 3 = Weak (Divided)

Figure 8. Measures of Group Cohesion: 1 = Strong, 2 = Moderate, 3 = Weak (Divided)

More than half of the participants (58 percent) considered the Sunni Arab community to be divided internally (no cohesion). Nearly half considered the Iraqi government to be divided (46 percent) and only a third considered the Islamic State to be divided (33 percent). In other words the Islamic State was perceived as more cohesive than either the Iraqi government/state or the Sunni Arab community (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Perceptions of Group Division “Divided” indicates the percentage of participants who chose the dot pattern indicating least cohesion for each of three groups (Iraq, the Islamic State, Sunni Arabs).

Figure 9. Perceptions of Group Division “Divided” indicates the percentage of participants who chose the dot pattern indicating least cohesion for each of three groups (Iraq, the Islamic State, Sunni Arabs).

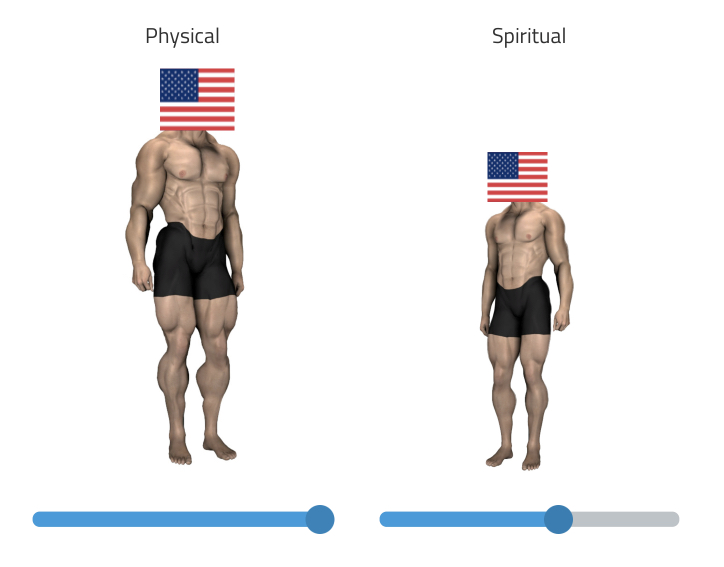

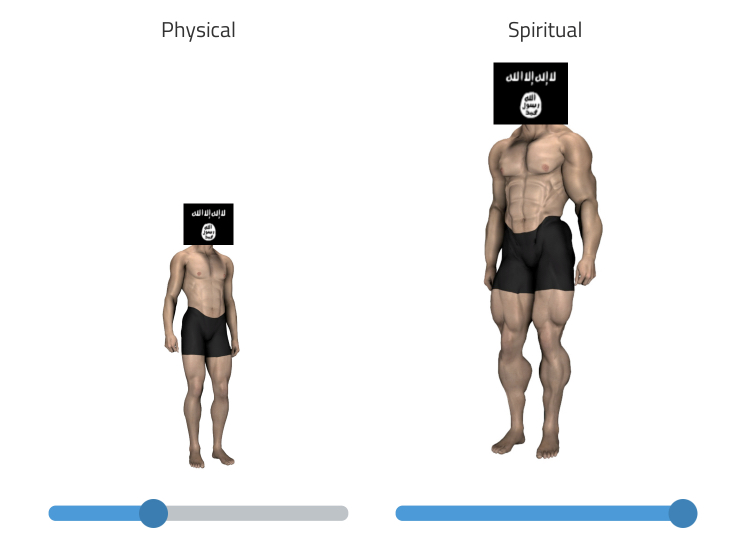

Spiritual Formidability versus Physical Formidability

In the authors’ earlier study with frontline combatants in Iraq, they found that both avowedly religious Islamic State fighters and avowedly secular PKK fighters (the only force that held fast against the Islamic State onslaught in summer 2014) did not see physical formidability as important. They argued that most important was spiritual formidability (ruhi bi ghiyrat, in Arabic and Kurdish). Thus, the authors adapted measures of physical formidability to spiritual formidability, comparing the relative impact of physical and spiritual formidability on willingness to fight (Figure 10). This earlier field study with frontline combatants demonstrated the external validity of spiritual formidability measure. Overall, frontline combatants (peshmerga, Sunni militia, Iraqi Army, PKK, the Islamic State, al-Qa`ida/Jabhat an-Nusra) judged the United States high in physical formidability but low spiritually, while judging the Islamic State low physically but high spiritually.

Figure 10. Average Judgment of Spiritual Formidability versus Physical Formidability of United States versus the Islamic State by frontline combatants using touch-screen slider on a tablet (based on results in Gómez et al., 2017)e

In the post-Islamic State Mosul sample, the gap between physical and spiritual formidability is also highest for the United States versus the Islamic State (Figure 11). U.S. forces were perceived as physically the strongest but were among the spiritually weakest. Iran and the United States were the only factions whose physical formidability trumped their spiritual formidability. The Iraqi Army, Shiite militia, peshmerga, and the Islamic State were considered the strongest in spirit; and only the physical prowess of the Iraqi Army matched its spiritual prowess, with both being relatively high. By contrast, ratings of the Iraqi Army by frontline combatants before the retaking of Mosul were much lower, especially spiritual strength. The perceived spiritual formidability of the Islamic State was also relatively high, but lower than the authors previously found among frontline combatants before the group lost Mosul. Participants perceived the Sunni community as having the lowest spiritual strength; however, those most inclined to see (and lament) the Sunni community’s post-ISIS spiritual decline were liable to be in favor of establishing a Sunni homeland (r = −.25, p = .05), which some participants justified as a means to overcome the community’s current perceived weakness.

Figure 11: Perceived Spiritual vs Physical Strength by Civilians coming out from under Islamic State rule, 2017. An asterisk (*) indicates significant differences between physical and spiritual formidability (p < .001)

Figure 11: Perceived Spiritual vs Physical Strength by Civilians coming out from under Islamic State rule, 2017. An asterisk (*) indicates significant differences between physical and spiritual formidability (p < .001)

Overall, whereas physical formidability was not related to cohesion, spiritual formidability was positively related to cohesion; that is, negatively correlated with inner division (opposite of cohesion): for the Islamic State, r = −.32, p = .01; for the Iraqi Government, r = −.44, p < .001; for the Sunni community, r = −.25, p = .05. In other words, the higher perceived spiritual formidability of each group, the higher the perceived cohesion.

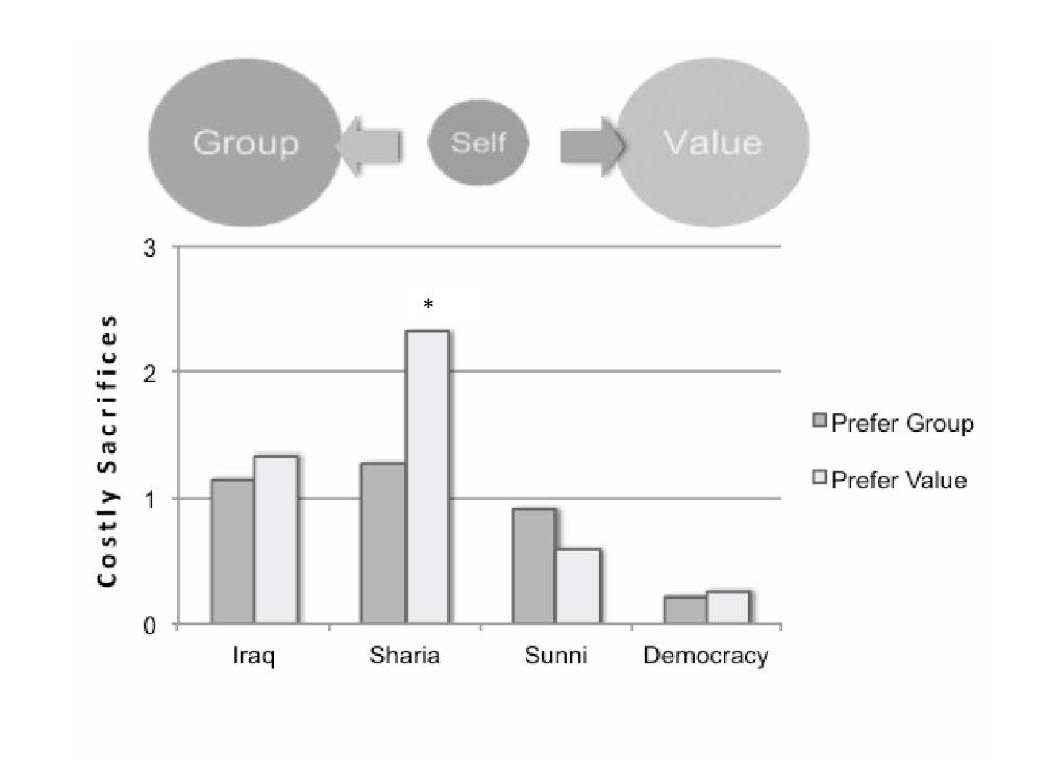

Commitment to Values versus Groups

In earlier research in North Africa and Europe, the authors found that fusion and sacred values were independent predictors of willingness to make costly sacrifices, including fighting and dying, but their interaction maximized such willingness.5 Yet when push comes to shove, which takes precedence—commitment to one’s primary reference group or commitment to one’s sacred value? In order to answer this, participants were asked to choose between sacred values and fused groups using a dynamic measure for choosing between Value and Group.

The authors focused on the most important group and most important value that each participant had previously indicated. Most people indicated family as their most important group and sharia as their most important value (as might be expected from evolutionary theory). Thus, the main dilemma was to choose between family versus sharia (Figure 12). Most people choose commitment to group, especially the family, over any value (as found in the authors’ previous online studies of Western Europeans noncombatants). Those who chose value over group were also more willing to make sacrifices for the value than those who chose group over value (consistent with the authors’ previous findings for some frontline combatants in Iraq).f

Figure 12. Group versus Value. Most people choose commitment to their most important group (which was most often the family) over any value; however, those who chose value over group (most often when sharia was the value) were more willing to make greater sacrifices for the value than those who chose group over value. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant preference for sharia over any group (p < .001)

Figure 12. Group versus Value. Most people choose commitment to their most important group (which was most often the family) over any value; however, those who chose value over group (most often when sharia was the value) were more willing to make greater sacrifices for the value than those who chose group over value. The asterisk (*) indicates a significant preference for sharia over any group (p < .001)

Supporters of a Unified Iraq versus supporters of a Sunni Arab Homeland under Sharia

Support for an independent Sunni Arab homeland is negatively correlated with democracy, r = −.28 p = .02, and sharia is also negatively correlated with democracy, r = −24, and p = .04. Sharia is positively correlated with independent Sunni region, r = .23, p = .05, but not with a unified Iraq. Participants who simultaneously value both a Sunni Arab homeland and sharia also are more fused with Sunni Arabs, r = .23, p =.05; more willing to sacrifice for Sunni Arabs, r = .50, p < .01, and sharia, r = .43, p < .001; and less willing to sacrifice for a unified Iraq r = −.25, p = .04 and democracy, r = −.30, p = .03. Sunni homeland and sharia supporters also perceive the United States as having low spiritual strength, r = −.27, p = .03, as with Iran as well r = −.28, p= .03, and supporters of a Sunni homeland and sharia also tended to suggest in justifications that the current military advantage of the United States (and to a lesser extent Iran) would not long endure owing to a lack of sustaining spiritual power.

Perhaps most important for policy planners seeking to maintain cordial relations with the region is that participants who value both an independent Sunni Arab homeland and sharia show the least support for democracy, r = −.33, p < .01, and these people are more willing to make costly sacrifices forハthese values than those who support a unified Iraq.

Conclusion

“America wants to impose democracy only to divide the Sunni people; [the Islamic State] gave us hope with sharia.”g

On December 9, 2017, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared victory over the Islamic State, claiming that its defeat was “won with our unity and determination.”6 Yet, this study’s participants still perceive a comparable measure of unity and determination for the Islamic State, at least in the sense of being relatively cohesive (more so than the Iraqi government/state itself) and spiritually formidable (which the authors’ frontline studies indicate is a predictor of “will to fight”). Moreover, results intimate that a significant number of supporters of a Sunni Arab homeland and sharia likely still adhere to what they at least initially perceived to be Islamic State core values. For example, nearly two-thirds of supporters of both a Sunni Arab homeland and sharia (32 percent of all participants) indicated that sharia was the Islamic State’s most cherished value. Moreover, the underlying conditions of political and confessional conflict that caused people to initially embrace the Islamic State have not appreciably changed in people’s minds.

Indeed, there are numerous reports from participants and others of Islamic State remnants regrouping: for example, under the mantle of Jaysh Ahrar al-Sunnah, or Army of the Sunni Freemen.h In Kirkuk militants have carried out more than a dozen monthly guerilla-style attacks since their putative defeat. When asked if people expect the Islamic State to be completely eliminated, almost all of the participants emphatically answered “no.” When asked what will become of the Islamic State, answers revolved around two main themes: 1. It will operate as secret Islamic State cells or Islamic State-like groups, and 2. The Islamic State will wage insurgency again with its old tactics, such as bombings, assassinations, and small hit-and-run attacks.

The people who supported the Islamic State were Sunni Arabs who lived in Iraq’s Sunni Arab nationalist heartland. Many still believe that the Sunni Arabs should control Iraq, and the Shi`a should be subdued or expelled. Now that the Shi`a-dominated Iraqi Army, backed by the United States and Iran, has overcome the Islamic State and taken control of Iraq, what may be a significant and committed portion of these people want their own homeland, and they want it grounded in sharia law as Sunni Arabs understand it (a strict and extreme version of which was preached and practiced by the Islamic State).i

The United States and its allied coalition, however, are committed to a unified Iraq and, in principle, to democratic rule. Post-Islamic State coalition efforts are focused on supporting forces willing to commit to a unified Iraq. Today, these forces include Iraqi Shi`a (who now control the government) and some Sunni Arabs willing to work with the government. Militarily, the forces for a unified Iraq side have the material advantage in manpower and firepower. But what may be a critical finding is the apparent willingness of supporters of both sharia and a Sunni Arab homeland to make greater sacrifices than those who support a unified Iraq. This points to the possibility that a Sunni-based insurgency for the sake of sharia-based society may well reemerge to compete with forces backing a unified Iraq, particularly because those forces are viewed as threatening Sunni Arabs and their young people’s yearning for a corruption-free society under strong leadership.

One important theory-based but practical implication of this research is that appealing to spiritual values may be more effective than appealing to material values in motivating people to carry out actions (including sacrifices) to help improve the political and security situation in Iraq.

The research also suggests that spiritual values could be leveraged as ‘wedge issues’ to divide groups such as the Islamic State from supporting populations. This could be done by focusing on violations of sharia and traditional Sunni practices, including: behaviors that create divisions within society (fitna) and undermine the social solidarity of the community, killing foreigners just because they’re foreigners especially if they were previously accepted as a local guest (dhif), harming women and children, and so forth.j Focusing on the spiritual values that participants believed they initially shared with the Islamic State but which they feel the Islamic State subsequently distorted or corrupted represents perhaps the least costly means to fragment support for the Islamic State and to foster cohesion amongst those who oppose the Islamic State.k Nevertheless, it would be counterproductive to rely exclusively on negative or mass messaging, as implied by one former imam who recruited for the Islamic State but claimed to have left because the Islamic State “violated sharia and Islamic tradition.” He told the authors that: “The young who came to us were not to be lectured at like witless children. We have to provide a better message, but a positive one.” He went on to say that the message needs to be in a cultural frame that inspires them “from within their hearts.”

The Islamic State may have lost its ‘caliphate,’ but it has not necessarily lost the allegiance of supporters of both a Sunni Arab homeland and sharia to its core values, especially faith in strict sharia law. Unless the underlying conditions of political and confessional conflict that caused people to initially embrace the Islamic State appreciably change in the direction of mutual tolerance, and those core values can be reconfigured to accommodate that change, the specter of the Islamic State will likely endure. Appeal to a Golden Age revived in a glorious future—so unlike the distressing present and much of the recent past—will continue to have a powerful attraction for the region’s Sunni Arab population. The results suggest such an appeal and attraction needs to be leveraged rather than denied so as to forestall the emergence of a violent successor to the Islamic State.

Without the laborious development of institutions that underpin democratic governance of the kind that took Europe and the United States more than two centuries to foster, democracy may not in the foreseeable future be very good at adjudicating across tribal, ethnic, and confessional boundaries and conflicts (any more than in family matters). The focus on wedge issues, at least for local populations in Iraq and the wider Levant, might better target the promotion of interpretations of sharia and recognition of Sunni Arab cultural preferences that are tolerable to other confessional and national allegiances in the region. CTC

Scott Atran is research director in anthropology at France’s National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), research professor of public policy and psychology at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), and research fellow at the Changing Character of War Centre (University of Oxford). Hoshang Waziri is a research fellow at ARTIS International. Ángel Gómez is Professor of Psychology at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (Spain). Hammad Sheikh is a postdoctoral fellow in psychology at the New School for Social Research (New York). Lucía López-Rodríguez is an assistant professor of psychology at the Universidad de Almería (Spain). Charles Rogan is presidential assistant at ARTIS International. Richard Davis is Professor of Practice at Arizona State University and a research fellow at the Changing Character of War Centre (University of Oxford).

All authors participated as researchers under the auspices of ARTIS International.

Substantive Notes

[a] Pre-study interviews with policymakers in the United States and Europe and field studies in IDP camps in the Mosul region of Iraq were carried out with support from the Carnegie Corporation. Development of the theoretical framework for exploring willingness to make costly sacrifices for the sake of material interests versus abstract ideals and values, and experimental validation of that framework and associated measures outside of the conflict area, was supported by the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the National Science Foundation. Psychological measures were developed with support from the U.S. Office of Naval Research.

[b] These include the Norwegian Refugee Council, REACH, Terre Des Hommes, the World Health Organization, the Danish Refugee Council, UNICEF, UNFPA, the International Organization for Migration, Emergency Health Care by Kuwait Government, QANDIL, Médecins Sans Frontières, and the International Medical Corps.

[c] There was also a modest rise in Mosul’s standard of living, confirmed by European government sources.

[d] Study participants tended to support the imposition of collective prayers and zakat (charity) as creating social solidarity, but also the requirement that women wear the niqab (face covering) in public. The physical and juridical subordination of women represents a fundamental clash with Western values and interventions not readily reconciled at present, and also with regard to (lack of) tolerance of minorities and their equality before the law. As in Afghanistan, perceived foreign forcing of gender equality incites intense and often violent opposition, and is a constant motivator of local insurgency. Historically, Mosul has been a center of Sunni Arab nationalism, rooted in social and religious conservatism. For example, Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahab, founder of the Wahabi movement and a spiritual icon for the Islamic State, studied Islam and salafism in Mosul. The Islamic State legitimized sharia as a governing system. This came in the wake of Saddam Hussein’s intense Faith Campaign to Islamize society, especially the army and educational system, which began in the 1990s in an effort to undermine tribal loyalties and enlist Sunni Arab support across the region in opposition to Sunni rival Saudi Arabia, Shi`a Iran and the Judeo-Christian West. Participants who selected sharia as their most sacred value, and favored it over their family, were asked how they saw other “People of the Book” (Ahlu al Kitab), especially Christians. Participants stated that Christians must pay poll tax (Jizya) as sharia demands. When we asked about Yazidis their answer, as one participant typically put it, was: “We will not kill them but we will make them to convert to Islam.” Insofar as the Islamic State did ask Yazidis to become Muslims before it started massacring them, this position is not contrary to the Islamic State’s.

[e] To illustrate how the measure was used in the field, in this case by a peshmerga fighter, see video available at https://youtu.be/FjKu9Gt-FbY. The viewer will see that the measure was readily understood and easily manipulated.

[f] For each given value, the authors regressed sacrifices on sacredness and fusion (with different groups). Sacredness positively predicted sacrifices for all values (ps < .01); however, fusion did not predict sacrifices for any value, no matter the group.

[g] These were the words of one of the young Sunni male participants in the study.

[h] Participants told the authors that high-level Islamic State personnel can readily bribe their way out of capture and detention, whereas low-level associates of the group, likely including some of the participants themselves, were often just members of the local working population. As before, Islamic State intelligence about the local situation likely involves placing operatives or cultivating informants in a variety of common occupations, such as sellers of goods in stalls and shops near privileged targets and sources of information (e.g., near police stations, municipal buildings, courts, popular markets, sites of NGO and foreign aid activities, among other pursuits), and so forth.

[i] Participants were especially wary of Shi`a Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF). On March 8, 2018, Iraqi Prime Minister Abadi issued a decree granting PMF the same rights and salaries as the Iraqi Army. PMF comprise some 50 militia groups, totaling about 150,000 fighters, most trained and backed by Iran (and often directed by Iran’s Quds Force, the Revolutionary Guards’ extraterritorial arm). Although the decree subjects PMF to Iraqi military law, it actually says nothing about integration with the Iraqi Army or about relinquishing operational command or control of its heavy weapons to the Iraqi Army.

[j] What makes religious law, and the universal religions generally, so adaptable over vast expanses of time and cultural contexts, is their open-texturedness, allowing for a vast range of reinterpretation depending upon ever-changing events and interests in the here and now (and a chief occupation of weekly preaching by imams, priests and rabbis). Scott Atran and Jeremy Ginges, “Religious and sacred imperatives in human conflict,” Science 336:6,083 (2012): pp. 855-857.

[k] No messaging is effective in a social vacuum. Al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State demonstrated the importance of intimate community service engagement with personal social networks, and adaptation of positive messaging to local needs and aspirations. This approach contrasts with the negative mass messaging featured in many Western public diplomacy approaches to “counter-narratives.” For a telling analysis, see Elisabeth Kendall, “War-torn Yemen may attract jihadi fighters from Syria and Iraq,” Financial Times, February 27, 2017.

[2] Jeremy Ginges, Scott Atran, Douglas Medin, and Khalil Shikaki, “Sacred bounds on the rational resolution of violent political conflict,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104:18 (2007): pp. 7,357-7,360; Scott Atran, Robert Axelrod, and Richard Davis, “Sacred barriers to conflict resolution,” Science 317:5,841 (2007): pp. 1,039-1,040; Morteza Dehghani, Scott Atran, Rumen Iliev, Sonya Sachdeva, Douglas Medin, and Jeremy Ginges, “Sacred values and conflict over Iran’s nuclear program,” Judgment and Decision Making 5:7 (2010): pp. 540-546; Jeremy Ginges and Scott Atran, “War as a moral imperative (not practical politics by other means),” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278:1,720 (2011): pp. 2,930-2,938; Richard Davis, Hamas, Popular Support, and War in the Middle East (New York: Routledge, 2015); Scott Atran, “The Devoted Actor: Unconditional cooperation and intractable conflict across cultures,” Current Anthropology 57:S13 (2016): pp. S192-S203.

[4] William B. Swann, Jr., Ángel Gómez, John F. Dovidio, Sonia Hart, and Jolanda Jetten, “Dying and killing for one’s group,” Psychological Science 21:8 (2010): pp. 1,176-1,183; Ángel Gómez, Lucia López-Rodríguez, Alexandra Vázquez, Borja Paredes, and Mercedes Martínez, “Morir y matar por un grupo o un valor. Estrategias para evitar, reducir y/o erradicar el comportamiento grupal extremista,” Anuario de Psicología Jurídica 26:1 (2016): pp. 122-129; Harvey Whitehouse, “Dying for a group: Towards a general theory of extreme self-sacrifice,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences (in press).

[5] Scott Atran, Hammad Sheikh, and Ángel Gómez, “Devoted actors sacrifice for close comrades and sacred cause,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111:50 (2014): pp. 17,702-17,703; Hammad Sheikh, Ángel Gómez, and Scott Atran, “Empirical evidence for the devoted actor model,” Current Anthropology 57:S13 (2016): pp. S204-S209.

Skip to content

Skip to content