Abstract: Hezbollah’s culture of martyrdom has helped sustain the organization’s manpower needs since the organization’s founding. A critical question, however, is how the group communicates this narrative to its base, especially given recent challenges to the group’s legitimacy as a result of its intervention in Syria. The ‘Party of God’s’ online content reveals that it does so in part by using the mothers of martyred fighters to promote the culture of martyrdom. Mothers possess unique access in society due to their ability to shape the minds of the next generation. As a result, Hezbollah uses their voices to amplify its propaganda in a way that resonates with the group’s following. Signs of tension between the party and these women, however, could pose challenges to this strategy in the future.

In March 2017, an article on Hezbollah’s online media outlet Arabipress featured a poem by the Egyptian poet Hafez Ibrahim (b. 1872) that opens with the line, “Our mothers are like our schools; pampering them means securing our future.”1 Seven months earlier, the same website posted a music video in which a young man crooned, “For you, my mother,” sentimentally dramatizing their close relationship and her reaction to his eventual martyrdom.2 Frequently, Hezbollah’s media also quotes a song by the renowned Lebanese musician Marcel Khalife to honor the mothers of its martyrs: “ajmal al omahat” (the most beautiful mother).3 These items are not simply rhetorical devices; they also serve a strategic purpose. Hezbollah uses the mothers of its fallen fighters to sustain a culture of martyrdom that provides it with a self-replenishing pool of fighters, a critical function throughout the group’s history but especially today.

Since late 2012, Hezbollah’s founding principle of resistance to Israel has been eclipsed by its intervention in Syria on behalf of the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Mounting casualties and increasing resentment4 among the group’s base in Lebanon have, to some extent, challenged the pervasive culture of martyrdom that sustains its manpower. This is where the mothers of martyrs come in. In order to retain control over the martyrdom narrative, Hezbollah uses these mothers to relay stories that promote both self-sacrifice and the sacrificing of one’s children to the resistance. As the opening examples illustrate, the cooptation of popular refrains are meant to capitalize on a deeply held local value: the importance of mothers in building a society. Mothers, therefore, represent a crucial demographic for Hezbollah, serving as a bridge between the party leadership and the community from which it draws its fighters. In order to convince these women to sacrifice their sons, the party shrewdly uses the voices of those who have already done so. Signs of tension between the group and the mothers of its martyrs, however, could call into question the viability of this strategy in the long term.

The Culture of Martyrdom

Throughout the first three decades of Hezbollah’s existence, its role in the “axis of resistance” against Israel imbued it with legitimacy, attracting ideologically motivated fighters to its cause. Equally important in this respect, however, was the group’s culture of self-sacrifice that regarded martyrdom as a blessing. Whereas the resistance and self-sacrifice narratives no doubt became intertwined and fed off of each other, Hezbollah’s concept of martyrdom also took on a life of its own, independent of political slogans against Israel. Martyrdom has always occupied a sacred space in the Shi`a religious tradition, dating back to the martyrdom of the Prophet’s grandson Husayn in the seventh-century Battle of Karbala. But the Shi`a cleric Imam Musa al-Sadr, the founder of Lebanon’s Amal movement, helped transform it into a tool of recruitment. Throughout the 1970s, al-Sadr encouraged his followers to draw inspiration from martyrdom, in the hope that each instance would unleash a flood of revolutionary zeal and thereby strengthen his forces.5 Hezbollah, founded by a stream of Amal defectors with Iranian assistance in the early 1980s, capitalized upon this culture—holding public funerals and plastering images of its martyrs across towns to reap the highest possible reward from each casualty incurred in its resistance to Israel. The strategy resonated among the group’s base. “Nobody here wants war,” said one Lebanese man at a Hezbollah funeral in the town of Barachit in 2006. “[But] for each martyr that [has died], there will be a thousand more like them.”6

The culture of martyrdom persists, but contemporary developments threaten its potency. First, despite Hezbollah’s public branding as the defender of Lebanon’s Shi`a community, the group’s de facto prioritization of the Syria fight over that against Israel has evidently cheapened the cause for which martyrs are dying.7 Second, payments to martyrs’ families have reportedly been cut due to rising war budgets, a step that threatens to provoke discontent.8 Third, Hezbollah’s combat fatalities over almost five years in Syria exceed those sustained over the 18 years from its founding in 1982 until Israel’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2000.9 The group is suffering significant casualties, and for a cause that many are questioning. Indeed, the party seems to be concerned that as martyrs accumulate, they may begin to alienate more followers than they galvanize. Public funerals have become less frequent in the present day, for example, suggesting that party leadership no longer views celebrations of martyrdom to be as useful as they once were. Experts also estimate that the group has only acknowledged about half of its actual combat deaths in Syria—even actively covering up the causes of death in some cases, according to some reports.10 Against this backdrop, Hezbollah’s ability to control the narrative surrounding martyrdom is more critical—and maybe more vulnerable—than ever.

The Martyr’s Mother as Spokeswoman

Perhaps the most compelling way to promote the culture of martyrdom is through an endorsement by the martyr himself. Indeed, this happens to an extent in ‘last will’ videos recorded by fighters and released after their death in battle. But the martyr, of course, can no longer speak, so his family—and his mother in particular—represents his next-best spokesperson.

The benefit of using mothers as a mouthpiece is both spiritual and practical. On a spiritual level, a mother thanking God for her son’s martyrdom constitutes a powerful image, given the universal nature of maternal love and the instinct to protect one’s children from danger. Accordingly, Hezbollah uses mothers to propagate the martyrdom narrative in an emotionally resonant fashion. On a practical level, the martyr’s mother serves as a crucial intermediary between party officials and other women who might be willing to sacrifice sons to the cause. Hezbollah’s ability to reach out to these other women is critical because they will educate the next generation of fighters, hopefully (from Hezbollah’s point of view) instilling within them the values of self-sacrifice and martyrdom.

Mothers are also important players when their sons reach military age. Some stories11 on Hezbollah websites have made mention of young men requesting their mother’s written permission before leaving to wage jihad in Syria—suggesting that the mother often has at least some say in the matter, even if in practice the party may not require parental consent (or heed parental objections) before sending fighters to Syria. A mother’s blessing may also help relieve a son’s guilt at leaving his family, a critical element of strategic messaging given that many of these young men repeatedly ask their families to forgive them in ‘last will’ videos.12 Moreover, given the new trend of recruiting young and unmarried fighters, the mother’s opinion likely weighs particularly heavily in the minds of these younger recruits.13

Endorsement in written form is useful to Hezbollah not only to persuade potential fighters, but also as an insurance policy in case of martyrdom. A mother who has willingly surrendered her child is less likely to publicly blame the party for his death, as has happened in cases in which permission was allegedly not granted.14 It is for these reasons that Hezbollah’s propaganda has in recent years targeted women as much as the fighters themselves, if not more.

Hezbollah circulates a variety of materials, including purported letters from mothers to their martyred sons, personal narratives, voice recordings, and even documentaries featuring interviews with martyr families with a special focus on the mother. Virtually all of these mothers relay similar narratives. For them, the martyrdom of a son is a blessing that brings the entire family closer to God and Ahl al-Bayt (the Prophet Muhammad’s family), strengthening their resolve to sacrifice more to the resistance.a

Crafting the Martyrdom Narrative

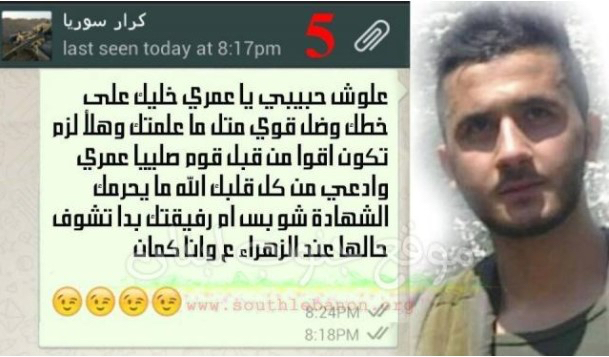

The process of celebrating martyrdom begins before death, with Hezbollah online content depicting women encouraging their sons to sacrifice themselves in battle. Arabipress, for example, published a news item in 2014 under the title “Mother of a Hezbollah Fighter in Syria: ‘God, Please Grant My Son Martyrdom, Please God!’”15 Another article, written in Hezbollah’s Arabipress in 2015, contains screenshots (see photos) of a conversation between a woman and her son who was at the time deployed to Syria by Hezbollah, in shock that he remains alive while his comrade has just been killed next to him in Syria. “Maybe Mahdi was ready for martyrdom before you … my dear, remain on your path, and stay strong like I taught you … May God not deny you martyrdom,” she wrote.16

After death, the mothers of dead fighters may express grief but ultimately treat martyrdom as a happy occasion, according to the script set by Hezbollah. Pro-Hezbollah press frequently publishes articles and videos that portray women thanking God for their son’s martyrdom—including one in October 2017 in which the mother of the martyr Ali Zaitar appears to kneel over her son’s burial site: “God has given me more than I deserve,” she repeats.17

Another important element of the mother’s narrative is the idea that sacrificing children brings one closer to God and Ahl al-Bayt. One mother in 2014 described feeling as though she had finally answered Imam Husayn’s call when she sent her son to Syria.b After his martyrdom, she went even further, announcing, “I feel as though I have passed God’s test.”18 Here, the historical Shi`a narrative is also key. The mothers frequently conflate current wars with early Islamic history, particularly the seventh-century Battle of Karbala. “Listen to me: you are in Karbala, with the Imam Husayn,” said one mother to her jihadi son in a voice recording published in April 2016. “Forget this world; everything will be gone one day. Just focus on Husayn, Karbala, and what happened there!”19 For these mothers, their sons who wage jihad very literally walk in the footsteps of the men killed in Karbala—and they themselves in the paths of Husayn’s mother, Fatima, and his sister Zainab (often referred to as Sayyida Zainab), women of Ahl al-Bayt who both sacrificed sons in the battle.

After a fighter’s martyrdom, the Hezbollah narrative emphasizes his enduring presence in his family’s life and beyond. In one interview, a woman claims of her martyred son, “He didn’t leave me … He is still among us. I smell his scent, I feel his presence, and he talks to me and makes me laugh.”20 Another example is found in a letter written in 1995 from the mother of a Bosnian ‘martyr’ to the mother of a Lebanese Hezbollah ‘martyr’ killed in Bosnia. Hezbollah’s Arabipress published an Arabic translation of the letter in March 2016: “These martyrs are the candles of our youth, the price of our freedom and resolve as Muslims … We all remember [your son] with great joy, and we can never forget him.”21 Given mounting Hezbollah casualties in Syria, the letter’s implication seemed timely and deliberate—that even those martyrs who die far from their homeland live on for years after their death.

Perhaps the most critical part of the narrative involves the notion that martyrdom should strengthen the resolve of others to sacrifice even more to the cause. After all, Hezbollah’s ability to replenish its ranks depends largely upon the degree to which one man’s sacrifice inspires others to follow in his path. Pledges to do so are common in the mothers’ narratives. One woman, in a short documentary film, claimed that after the martyrdom of her first son, Mahdi Yaghi, she hoped her other son, Ali, would also die a martyr’s death.22 Her wish was granted when Ali was killed in Syria in June 2017.23 In another conversation around the same time with the mother of Mustafa Badreddine, a senior Hezbollah official killed in 2016, the interviewer asks what she would tell her son a year after his martyrdom. “Your siblings, your grandchildren … all of us remain steadfast on your path,” she responds, “and we will not leave it until every last one of us is martyred, with God’s permission.”24

In these ways, the mother’s words are used to motivate young men and other mothers to make sacrifices for Hezbollah’s cause. The message resonates. In one particularly powerful and inflammatory video posted in August 2017, the mother of Hezbollah ‘martyr’ Mahdi Khadr bellows into a megaphone before a large crowd of men: “Raise your heads!” she orders, a phrase often invoked by Arab leaders to garner support and boost morale among the marginalized. She then directs them to repeat after her, with pride and honor: “At your service, Zainab!” The crowd obeys her command, erupting with boisterous chants in response.25

An article, written in Hezbollah’s Arabipress in 2015, contains screenshots of a conversation between a woman and her son fighting with Hezbollah in Syria, in shock that he remains alive while his comrade has just been killed next to him in Syria. “Maybe Mahdi was ready for martyrdom before you … my dear, remain on your path, and stay strong like I taught you … May God not deny you martyrdom,” she wrote.

Promoting the Narrative: Carrots and Sticks

While these narratives are likely authentic to a decent extent, Hezbollah appears to stage-manage them to ensure both uniformity and conformity. The group seems to rely upon an inner circle of families it trusts to toe the party line. In many cases, the same families appear repeatedly in Hezbollah’s media—in letters, interviews, and documentaries—whereas other families are not even granted the “privilege” of a published martyrdom announcement. The group also regularly features the families of its most prominent martyrs—including Badreddine and Imad Mughniyeh, the Hezbollah commander assassinated in 2008. The latter serves the extra purpose of demonstrating that if families of such stature have sacrificed their sons, anyone should be willing to do so.c The ‘martyrdom’ of Hassan Nasrallah’s son Hadi in 1997 has, in itself, become a talking point. “O, Sayyid [Hassan], you sacrificed a martyr as well, my brother,” wailed one mother as she addressed Nasrallah from beside her son’s coffin in early 2017.26 Another, in September 2016, proclaimed in an article, “I am the mother of a martyr … our sacrifices pale in comparison to [Hassan’s]!”27

This is not the only method Hezbollah employs to ensure adherence to the party line. Reports28 have emerged of party officials planted at public funerals to ensure proper comportment and to boost morale, as well as repeated visits by party members to the families of its martyrs.29 Hezbollah’s web content, moreover, shames those who react with excessive grief to a loved one’s martyrdom—as always, using the mother as an example. “Mohammad shouldn’t be cried over … no, no, no … Mohammad deserves for people to be happy for him because he reached heaven!” yells one woman in response to mourners weeping over her son’s coffin.30 Another mother, shown hugging her son’s corpse, holds back tears while repeating to herself that she won’t cry to avoid him seeing her upset.31 An additional way Hezbollah pressures mothers is by using the voices of their martyred sons. In a ‘last will’ video, the martyr Mahdi Yaghi tells his mother—in an obviously scripted segment—not to be sad when he is martyred and to try to behave in the way Fatima and Zainab once did.32 The speech is likely canned, as martyrs reading from scripts in other videos express the same sentiments toward their own mothers—including the martyr Hassan Ahmad Kanaan in a video published in 2014. “Do not be sad when you hear the news of my martyrdom, but rather hold on to the patience of Sayyida Zainab, peace be upon her.”33 These videos are also used to court mothers emotionally through what appear to be spontaneous words, such as a segment of Yaghi’s video when he is quietly prompted twice by the cameraman to speak to his mother.

In addition to emotional pressure and financial inducements, Hezbollah encourages sacrifice by granting the mothers of martyrs a unique symbolic status within the party. As mentioned previously, Hezbollah’s media draws frequent parallels between the mothers of martyrs and Sayyida Zainab, the sister of Imam Husayn revered by Shi`a Muslims for her bravery and sacrifices in the Battle of Karbala. Zainab’s rising status in Hezbollah doctrine—protecting her shrine in Damascus has served as a central justification for involvement in Syria34—has only rendered these comparisons more poignant and effective. Such parallels therefore lionize the sacrifices of Hezbollah women, signaling that a son’s martyrdom will earn them eternal glory in the eyes of God. Hierarchies of sacrifice are also present within the party’s propaganda, with the mothers of martyrs at the top. A Mother’s Dayd special from Hezbollah’s media outlet al-Manar, for example, featured the mother of a wounded fighter who offered her own disclaimer at the end, arguing that Mother’s Day should be dedicated fully to the mothers of martyrs for they are the ones who have sacrificed the most.35

Signs of Trouble

Outside Hezbollah’s own carefully curated media, some mothers have begun to question the group’s justification for the Syria intervention and its narrative of martyrdom. These accounts have appeared in both traditional and social media. In May 2015, a Twitter user under the handle “Um al Hasan” (mother of Hasan) tweeted, “Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah, I want my son back from Qalamoun. It is enough that one already died.”36 Fourteen minutes later, the same user tweeted again under the Arabic hashtag “we want our sons.”37 Although the hashtag has also been used frequently as a rallying cry for Palestinian martyr families against Israel, a number of other users followed Um al Hasan’s example, tweeting the hashtag to protest Hezbollah’s involvement in Syria.e

Rumors of discontentment among mothers have also appeared in Lebanese traditional media, despite Hezbollah’s known efforts to intimidate reporters. For instance, the news outlet Al Mustaqbal reported in the spring of 2016 that a number of mothers of Hezbollah fighters killed in Syria had refused to welcome delegations of party members on Mother’s Day.38 In June 2016, the website quoted the mother of a martyred fighter addressing Hassan Nasrallah: “Why, Sayyid [Hassan]? This was not what we agreed to. We agreed that my son would learn religion and fight Israel … What is there for us in Syria? My son’s blood is on your hands.”39 In another article published by Al Joumhouria, the mother of a Syria casualty dared to ask the ultimate question more explicitly: “Did my son truly die a martyr’s death?”40

Admittedly, these reports appear largely in anti-Hezbollah Lebanese media, but even if they are not reliable across the board, their very existence may threaten the party’s legitimacy by raising doubts in its followers’ minds. Hezbollah’s culture of martyrdom relies on the mothers of martyrs to promote martyrdom wholeheartedly as the ultimate form of religious devotion; it does not allow for debate over what constitutes a martyr’s death. The breaking of taboos on these questions therefore elevates concern among party leaders about growing disillusionment among its rank and file. If this discontentment further takes hold and affects actual decision-making, it would not be the first time a group of mothers in the region had influenced military decisions through grassroots activity. Perhaps ironically, Israel’s “Four Mothers” movement, which decried what many Israeli soldiers’ mothers saw as the squandering of young lives in an unnecessary war in Lebanon, helped prompt the IDF’s withdrawal from the country in 2000.41

Conclusion

While signs of tension between Hezbollah and its community of mothers is undoubtedly a source of anxiety among its leadership, the severity of these concerns will depend largely upon the trajectory of the Syrian war and the party’s role in it. If combat fatalities continue unabated, the internal challenges described here could grow in importance and eventually overshadow the additional problem of Hezbollah’s loss of legitimacy in the eyes of many Arabs across the region. However, reports of discontent have been appearing on an occasional basis for several years and without much apparent change to Hezbollah’s ability to carry on the fight in Syria.

For now, the party seems to be managing this trend. Hezbollah also holds a subtler psychological advantage. For many of these families, blindly accepting the narrative of martyrdom may be less emotionally wrenching than questioning whether a child’s death was worth the pain. Until more families are ready to face such difficult questions, Hezbollah may continue to capitalize on the cult of martyrdom to the detriment of Lebanon’s Shi`a community. CTC

Kendall Bianchi’s research focuses on security issues in the Middle East. She was previously a research assistant in the Military and Security Studies Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Before this, she studied Arabic in Jordan on a NSEP Boren Scholarship and in Morocco on a U.S. Department of State Critical Language Scholarship. Her work has also appeared in Foreign Affairs and on the Washington Institute’s Fikra Forum.

Substantive Notes

[a] These observations are based on the author’s review of Hezbollah propaganda materials posted online by the group.

[b] The martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali, a grandson of the Prophet Mohammed, at the Battle of Karbala in 680 A.D. is central to Shi`a identity. Husayn is revered by Shi`a Muslims.

[c] These observations are based on the author’s review of Hezbollah propaganda materials posted online by the group.

[d] Most Arab countries celebrate Mother’s Day in March.

[e] These tweets were observed by the author.

Citations

[1] Qasem Istanbuli, “Our mothers are like schools,” Arabipress, March 8, 2017.

[2] Mahmoud Shahin, “For you, my mother – a message from a member of the resistance to his mother,” music video posted to Arabipress, August 29, 2016.

[3] See, for example, “The most beautiful mother: Listen to what the mother of the martyr Ali Hassan Ibrahim said,” Arabipress, October 10, 2016. See also “The most beautiful mother … The mother of the martyr Mohammad Jaafar Dagher talks about her son,” Arabipress, May 21, 2014.

[5] Fouad Ibrahim, “Al-Shahada: a Centre of the Shiite System of Belief,” in Madawi al-Rasheed and Marat Shterin eds., Dying for Faith: Religiously Motivated Violence in the Contemporary World (London: I.B. Taurus & Co Ltd, 2009), p. 118.

[8] Hanin Ghaddar, “Hezbollah’s Women Aren’t Happy,” Tablet Magazine, October 12, 2016.

[9] “Hizbollah’s Syria Conundrum,” Report No. 175, International Crisis Group, March 14, 2017.

[10] Rabia Haddad, “Top Secret Casualties of Hezbollah,” Al Modon, April 20, 2015. See also Leila Fadel, “Cemetery for Hezbollah Martyrs Continues to Grow,” NPR, October 12, 2012.

[11] “The story of the martyr Abbas Alama between him and his mother,” Arabipress, June 6, 2017.

[12] For example, see “Last will of the martyr Mahdi Mohammad Yaghi – full (serious and unprompted),” YouTube, September 20, 2013. See also “In video: the martyr Qasem Shamkha through his will: forgive me,” Arabipress, November 7, 2016.

[13] Ghaddar.

[14] Suha Jafal, “About the mother of the victim Yaser Ali Shahla, who rebelled against Hezbollah officials,” Al Janoubia, July 31, 2015.

[15] “Mother of a Hezbollah fighter in Syria: ‘O God, please grant my son martyrdom, O God’,” Arabipress, April 10, 2014.

[16] “In pictures: conversation between the martyr Ali Abbas Ismael and his mother after the martyrdom of his friend, the martyr Mahdi Fakhreddine,” Arabipress, June 13, 2015.

[17] “This is what the mother of martyr Ali Zaitar said,” Arabipress, October 3, 2017.

[18] “The story of the martyr Zulfiqar Azzadin, in the words of his mother,” Arabipress, August 7, 2014.

[19] “In sound: Mother of a fighter in Aleppo sends him a voice recording … urging him toward Jihad and patience,” Arabipress, April 16, 2016.

[20] “Mother of the martyr Mohammad Ali Asad Bakri: My son before his martyrdom visited the Zainab shrine and told me he had asked her to have patience with me,” Arabipress, May 19, 2016.

[21] “Special: letter from the mother of a Bosnian martyr to the mother of the martyr Ramzi Mahdi in Lebanon, 1995,” Arabipress, March 7, 2016.

[22] “New, unique documentary about the Prince of Martyrs, the martyr Mahdi Yaghi,” Arabipress, July 9, 2017 (filmed at an earlier date). See 21:40.

[23] “Town of Asira/Baalbak presents the Zainabi martyr Ali Mohammad Hussein Yaghi,” Arabipress, June 3, 2017.

[24] “Mother of Jihadi Commander in her first recollection: rest easy, my dear, my son,” Al Manar, May 10, 2017.

[25] “Watch what the mother of martyr Mahdi Khadr said,” Arabipress, August 6, 2017.

[26] “In video: this is what the mother of the martyr Mohammad Basam Murad said to Sayyid Nasrallah,” Arabipress, January 31, 2017.

[27] “Letter from mother of the martyr Alaa Mustafa Aladdin ‘Jawad’ to Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah,” Arabipress, September 12, 2016.

[28] Fatima Hawhaw, “Shia oppositionists topple barrier of fear on Facebook,” Al Mustaqbal, June 5, 2013.

[29] Ghaddar.

[30] “This is what the mother of the martyr Mohammad Jouni said,” Arabipress, June 13, 2015.

[31] “The most beautiful mother: Listen to what the mother of the martyr Ali Hassan Ibrahim said.”

[32] See “Last will of the martyr Mahdi Mohammad Yaghi – full (serious and unprompted),” YouTube, September 20, 2013.

[33] “Will of the martyr Hassan Ahmad Kanaan (Malaak) – full version,” YouTube, March 24, 2014.

[34] Jean Aziz, “Hezbollah Leader Defends His Party’s Involvement in Syria,” Al-Monitor, May 2, 2013.

[35] “Mothers of the injured and the gift that keeps on giving,” Al Manar, March 21, 2017.

[38] “It is said that …,” Al Mustaqbal Issue 5676, March 23, 2016, p. 2.

[39] “33 Hezbollah fighters killed in Damascus suburbs; Their mothers say to Nasrallah, ‘this is not what we agreed upon,’” Al Mustaqbal Issue 5759, June 20, 2016, p. 3.

[40] Ali Husseini, “Mother of a fighter in Hezbollah: Is my son a martyr?” Al Mustaqbal, October 10, 2012.

[41] Deborah Sontag, “Israel Honors Mothers of Lebanon Withdrawal,” New York Times, June 3, 2000.

Skip to content

Skip to content