Abstract: A collection of 24 internal Islamic State documents—many of which are released for analysis here for the first time—highlights the group’s preoccupation and presentation of its ‘caliphate’ as an ideologically superior and pious society. In its own records, the Islamic State consistently framed its commitment to an extreme and ‘pure’ interpretation of Islamic doctrine in opposition to the malign influence of its ‘apostate’ or ‘infidel’ rivals. The documents indicate that through the imposition of policies including strict behavioral codes, educational reform, or forced ‘conversion’ of captive populations, the Islamic State sought to translate citizens’ compliance with pious ideals into long-term acceptance of the group’s ideological legitimacy and governing authority.

The establishment and governance of the Islamic State’s so-called caliphate from June 2014 marked a multifaceted victory for the group. It demonstrated supremacy over its rivals in military prowess, administrative and bureaucratic capabilities, and fulfillment of ideological commitments. In recent years, scholars and analysts have furthered understanding of the Islamic State’s myriad governance activities—from the functioning of its treasury and finances1 to the foundations of its judicial system2 and even its provision of goods, aid, and services.3 While the Islamic State governed through unrelenting authoritarianism, conformity of civilians was vital for the functioning and legitimacy of its proto-state project.4 As the Islamic State now seeks to recover from its territorial collapse, it is important to understand how the group sought to engender a—practically and ideologically—compliant population.

This article seeks to highlight an area of Islamic State policy that underpinned many of its governance practices: piety promotion. For the Islamic State, piety and devotion to its sharia translated into commitment to the group’s ideals and authority. The promotion of piety through behavioral strictures served to encourage the populace’s internalization of its ideology and rejection of rivals—whether local ‘apostate’ or foreign ‘crusader’ governments, or ‘infidel’ traditions and customs. Much of the Islamic State’s propaganda has focused on a ‘clash of civilizations’ or a ‘war against Islam.’5 The group’s battle for local hearts and minds came in the form of regulations to ‘correct’ and ensure uniformity of behavior. Most importantly, this was not limited to one sector of its society. Though afforded varying degrees of freedom within the ‘caliphate,’ the Islamic State’s focus on (its interpretation of) ‘Islamic’ piety ran across its policies for its members, governed civilians, and even captive ‘infidel’ populations. Close examination of such directives can shed new light on the Islamic State’s strategy of civilian control and the ideological legacy left in its wake.

Data for this study is drawn from 24 internal Islamic State documents dated between December 2014 and October 2016. These documents were obtained by U.S. military forces operating in Iraq and Syria and declassified through the Combating Terrorism Center’s Harmony Program, and many are released here for analysis for the first time. The full collection of documents, including English translation, is now available on the CTC’s website. The documents include a number of previously unseen fatwas, marriage contracts, official letters, public notices and memoranda, and administrative forms. Documents included in the collection reveal four key tenets of the Islamic State’s vision of ideological piety: shari‘i attire, travel restrictions, sex segregation, and religious ‘education.’ Though interdependent within the caliphate society, these will be examined in turn for analytical clarity. The examination of these primary sources provides rare insight into the Islamic State’s efforts to convert, coerce, and control individuals under its rule and discredit the practices of its enemies.

Shari‘i Attire

The introduction of conservative dress regulations, which preceded its caliphate declaration, was among the first signs of the Islamic State’s governance activities. The group’s aim was explicitly to end “debauchery resulting from grooming and overdressing” and manifested as a series of public information billboards as early as 2013.6 As the group continued to develop its bureaucratic infrastructure, a series of fatwas and policy notices were issued on official Islamic State stationery to formalize its parameters for what it considered pious behavior. Importantly, these regulations had an overt and disproportionate focus on women’s bodies and through them, from the group’s point of view, the protection of collective honor.

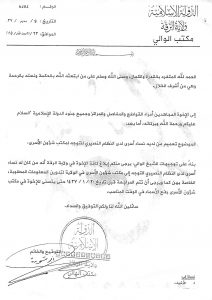

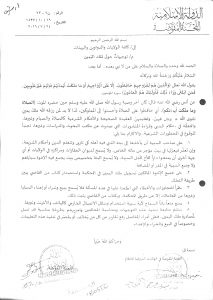

On December 18, 2014, four fatwas specifically concerning women’s shari‘i attire were released among a series of edicts from the Islamic State’s Research and Fatwa Issuing Committee. These documents reflect the group’s imposition of an increasingly strict and conservative female dress code, evolving from a niqab and abaya to include long gloves, socks, and a burqa with a thick, twin-layered veil covering the entire face and eyes. Even exposure of women’s eyes, particularly if eyeliner or make-up on the cheeks is used, was completely forbidden, and according to Fatwa 40 (Item D), it was necessary “to cover her eyes with even a light fabric to avoid temptation.”7 The seven required “characteristics of the legal hijab” were outlined in Fatwa 44 (Item H, see Figure 1). These include full body coverage of the face and hands; thick and loose-fitting material without adornment or colors to avoid attracting attention; and the prohibition of perfumes when women “go out and pass by men.”8 Most importantly, it stipulated that the attire “should not look like [clothing] that the infidel females wear.”9 Thus, through the introduction of ‘correct’ shari‘i attire, the Islamic State sought to distinguish itself from communities deemed indecent or impious, and avoid shameful ‘temptation’ by obscuring women’s bodies.

The accompanying three fatwas issued in December 2014 provide further justification for some of the most important characteristics of the shari‘i hijab. Fatwa 39 (Item C) stipulates that “colored abayas, especially those of tempting colors, shiny, velvet, or stretchy [fabric], are prohibited.”10 Interestingly, the document refers to hadiths that observe female companions of the Prophet wearing black headscarves.11 Rather than solely doctrinal citation, this newly released edict is the only Islamic State document (known to the author) that provides the group’s independent justification for its black dress code: avoidance of shame. Black is viewed as the color of least adornment and therefore the one that attracts the least attention from onlookers.12 Once again, the responsibility of avoiding ‘forbidden things’ and ‘tempting others’ is transferred to women through the imposition of full and unappealing coverage, eventually resulting in their visual erasure from the public sphere.

It is important to note that men were not exempt from the Islamic State’s dress code. Edicts issued in January 2015 point to the group’s wider concern with societal decency and rejection of impious customs. Fatwa 56 (Item M) prohibits “Western clothing” that is viewed as revealing and “mimics the ways of the infidels.”13 Similarly, Fatwa 55 (Item L) forbids “outfits that are low-hanging and drag below the heels.”14 This edict reinforces multiple Islamic State pamphlets and propaganda videos that emphasize the necessary short length of men’s trousers and dishdashas. However, though the group directly controlled men’s attire, it did not place emphasis on regulating male sexual desire. Instead, the Islamic State sought to eradicate illicit sexual interaction through control of women’s bodies and behavior. As such, Fatwa 44 (Item H) also specifies six “characteristics of immodesty.” These include a woman showing a part of her body or undergarments to a male stranger; flirting and associating with men; swaying, strutting, and walking seductively; and “making sounds with her high heels in order to show off what is hidden, which enflames passions more than looking at the ornaments worn.”15 In this way, women’s dress becomes a physical barrier to intermixing and zina (fornication or adultery), which are offenses under Islamic State rule punishable by lashing or even stoning.16 The minor details of women’s dress thus become a matter of public decency and societal morality, which are stipulated and controlled by men.

The violent punishment of women who contravene the group’s strictures has garnered significant scholarly and media attention on the issue of female members’ commitment to Islamic State’s ideals.17 The extreme interpretation and implementation of sharia law has also been documented as a key source of appeal to foreign—particularly Western—female recruits, who experienced Islamophobia or discrimination in their countries of origin.18 While this may have appealed to some who joined the group, Islamic State records also reveal a significant number of defiant women punished and imprisoned (see Item N).19 To meet its need for female-focused security, the Islamic State created a women’s branch of the hisba (morality police) in February 2014.20 A 2015 memorandum (Item O) announces the “reactivation” of the female hisba brigade and requests nominations for candidates to operate in Manbij, al-Raqqa, al-Mayadin, and al-Bukamal.21

Women enrolled in the hisba brigades were entitled to exclusive privileges, such as the ability to earn a wage, own and carry weapons, and patrol the streets without a mahram (male guardian or chaperone).22 However, even women acting within the Islamic State organization were not immune from scrutiny. Fatwa 41 (Item E) forbids a woman from wearing a gun holster or explosive vest over the abaya that would reveal her body shape below. However, it also supports the need for women to carry an AK-47; they are “permitted to do so because it is viewed as in the case of women carrying handbags.”23 Furthermore, a signed “written pledge” form (Item P) assigns protective responsibility to drivers who transport female workers in Raqqa province. The contractor is required to promise that all female passengers will wear the full shari‘i dress including covering their eyes during the journey and that they sit inside the car and do not stop en route. The signatory is obliged to accept the appropriate punishment for breach of these conditions.24 Thus, the Islamic State demonstrated that its own operatives were not above the law,25 reinforcing its aversion to corruption and dedication to caliphate-wide piety and compliance with authority.

The stated purpose of the female hisba brigades is “to deal with female violators” of the Islamic State’s behavioral codes, and their duties largely concerned meting out physical punishments. However, it is important to consider their strategic aim and impact. While violence provided the immediate impetus for conformity, in the long term it was presumably hoped that civilians’ attitudes would gradually change to embrace conservative dress, pious living, and the legitimacy of Islamic State’s sharia law.

Travel Restrictions

Throughout the Islamic State’s caliphate era, movement within and beyond the group’s territory was highly restricted. Solid external borders served to control and contain civilians within the ‘caliphate.’ First, they provided security to prevent infiltration from enemy forces or spies. Second, the Islamic State needed a substantial population to govern in order to legitimize its proto-state project; therefore, prevention of escape was necessary to justify the caliphate proclamation. In light of this, it is important to consider the framing of travel bans within the group’s documentation. Although security is noted as a significant concern, it is once again presented within a wider ideological struggle of a (physical and figurative) in- versus out-group. The Islamic State purported to offer the only ‘true’ interpretation and implementation of sharia law within the protective confines of its caliphate. Conversely, in dar al-kufr (lands of infidelity), all other governing actors are presented as impious, corrupt, and a threat to Muslims.

From as early as December 2014, the Islamic State’s Research and Fatwa Issuance Committee released an edict (Item K) that states “it is not permissible for the people of the Islamic State to travel to the territories of the infidels, and they should be prevented from doing so.”26 While temporary travel for commerce was deemed a necessary evil, it was accompanied with the caveat that “it is required to show the ability to reject the infidels, to hate polytheism, disbelief and its people, and to avoid having them as allies.”27 The wording of this edict echoes that of Fatwa 37 (Item A), which relates specifically to travel to Syrian regime territory. Importantly, Fatwa 37 highlights the responsibility upon exiting the caliphate of protecting the faith and justifies its travel ban due to “religiously prohibitive conditions.”28 The Islamic State thus exerted control over its citizens through its concern with the malign influence of other actors beyond its borders.

Similar to its dress and behavioral codes, travel restrictions disproportionately impacted the freedoms of women living under Islamic State rule. Even within the group’s territory, the preoccupation with illicit intermixing required women to be accompanied at all times by a mahram (see Item I).29 The woman’s mahram—ideally her husband—was granted complete control, even to the point of forbidding her to leave the house.30 The authority transferred to a male guardian was documented in a letter written by ‘Abu Fahd al-Tunisi’ (Item Q), presumably a male Tunisian Islamic State clerk or administrative officer. Here, ‘Abu Fahd’ grants permission for a man to approve his wife’s travel to Tunisia to visit her mother. The justifications for the travel permit reveal the group’s priorities. The letter emphasizes that the husband has “exhausted all kinds of harsh and soft techniques to make her change her mind” about traveling and that “if his wife doesn’t visit her family, she will ask for divorce and still find another way to go to her mother.”31 However, “the man has no concerns over the devoutness and piety of his wife,” and therefore it is ruled that allowing her to travel would be “choosing the lesser evil.”32 A woman’s temporary independence is thus, at least in this example, seen as a necessary concession to safeguard her marriage and religious piety.

The Islamic State demonstrated particular concern for women without a living mahram, or protection, outside of its ‘caliphate.’ In October 2015, the wali (governor) of Raqqa province issued a memorandum requesting all emirs and soldiers report details of any female relatives held prisoner by the Assad regime to the Islamic State’s Office of Prisoner Affairs (Item R).33 This was not the first time that the group had publicly condemned arrest of affiliated women by ‘apostates.’ In a video released in December 2014, Islamic State Commander Abu Ali al-Shishani threatened to kidnap Shi`a women and children and relatives of Lebanese soldiers in response to the arrest of his wife and two young children in Tripoli.34 Later that month, Fatwa 46 (Item J) explicitly prohibited widows and children of Islamic State “martyrs” to migrate to “infidel lands.” Concerned with ideological posterity and the group’s lineage, it warns against “the son of a righteous soldier living in the land ruled by tyrannical idolaters who may one day become a soldier in the devil’s army.”35 Again, the Islamic State framed its travel restrictions within a wider ideological struggle and clash between its ‘righteous’ soldiers and ‘apostate’ enemies.

Sex Segregation

To preserve public morality and avoid inappropriate contact between the sexes, the Islamic State instituted a full caliphate-wide sex segregation policy across its public spaces. Schools, hospitals, police patrols, and public-facing administrative departments all required women employees to manage the needs of its otherwise inaccessible female civilians. In some cases, this recruitment drive and opportunity to contribute to the functioning and prosperity of the caliphate appealed to willing recruits. One such example is ‘Shams,’ a Malaysian medic then in her mid-20s, who documented her journey to the Islamic State and work therein as a neonatal doctor in al-Ṭabqa. Her ability to run her own all-female wing of the city’s hospital resonated with supporters worldwide, making her an influential recruiter for women seeking active roles in the proto-state.36

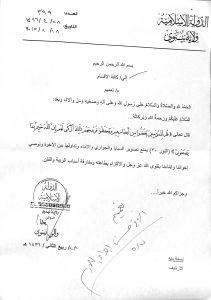

The ability for women to adopt professional roles within Islamic State’s public institutions certainly provided a source of physical and financial independence from their proscribed domestic roles as wife and mother. However, the group’s emphasis on religious piety and morality manifested in a series of directives affecting women’s operational capacity. For example, though female nurses were required to support male doctors, the sex segregation and mahram policies prevented ‘temptation’ by forbidding them to work alone without the supervision of a chaperone (see Item F).37 These edicts also directly impacted the treatment received by patients. Fatwa 43 (Item G) states the limitations for obstetrician-gynecologists to treat female patients within the Islamic State. It dictates that male doctors are only permitted to treat female patients if there are no female doctors available. However, it interestingly suggests that “a man can treat a woman and vice versa.” Importantly, it adds the caveat that “the doctor should not remain alone with the woman during the physical check-up or treatment and he has to look only at the required spot for treatment.”38 This is reinforced by an administrative order issued by al-Tabqa hospital (Item S, see Figure 2), which states that all female-section “nurses are completely prohibited from leaving an operation theater while there is a [female] patient in the room.”39 While on the one hand these documents reveal a shortage of female medics, on the other, they demonstrate prioritization of nurses’ duty of chaperoning female patients. It is not possible here to comment on the standard of care provided. However, it is clear that these policies sought to demonstrate the Islamic State’s unwavering commitment to morality, public decency, and piety—perhaps at the expense of service efficiency.

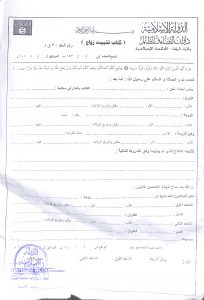

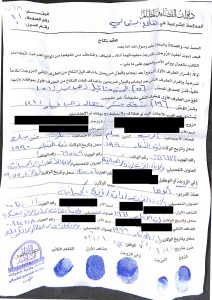

Concern for women’s guardianship is most acutely reflected in the Islamic State’s management of marital and family relations. Matrimony under the group’s rule was less concerned with finding true love than a transferal of responsibility from a woman’s father to a husband. A number of Islamic State marriage contracts are already published,40 and this article adds a further two to this collection for analysis. Both are stamped and authorized by the Islamic Court as part of the Department of Judiciary and Complaints, which is responsible for the conduct of shari‘i marriages. While the blank form issued by Raqqa province is entitled ‘Marriage Confirmation Document’ (Item T),41 the completed contract from Euphrates province bears the name ‘Contract of Nikah’ (licit sexual intercourse) (Item U).42 Some researchers and reporters consider such documents as evidence of the Islamic State recruiting women for “sexual jihad” to offer comfort and boost the morale of its fighters.43 While the term ‘nikah’ can imply temporary or unofficial marriage, it is critical to consider this in the context of the Islamic State’s issuance of a formal contract for lawful wedlock. Indeed, official birth certificates issued by the group require proof of marriage to confirm legitimacy of children.44 With a high mortality or ‘martyrdom’ rate of fighters, marriage in Islamic State was temporary by design. A nikah contract thus facilitated licit sexual intercourse in sometimes short-term partnerships and legitimized resulting offspring as descendants of the ‘caliphate.’

Both marriage documents emphasize the custodial responsibility of men over women. This concerns demonstration of financial provision as well as the guarantee of her ‘sexual purity’ prior to marriage. In line with the traditional custom of bride price, the contract from the Euphrates province (Item U) details the condition of marriage upon the groom’s immediate payment of five mithqals of 21ct gold (approximately 18 grams) followed by a delayed installment of 19 mithqals (approximately 70 grams).45 Furthermore, each contract requires confirmation of the bride’s virginity status, and that her guardian be present and provide a fingerprint to authorize the nuptials. In fact, the blank marriage confirmation document from al-Raqqa (Item T) omits space for the bride’s fingerprints, leaving headings for only her groom, guardian, and two (male) witnesses.46 The details of these documents indicate Islamic State’s concern with the legitimacy of the legal and religious institution of marriage. While the bride may financially benefit from the union, it is only through guarantee of her sexual purity and transferal of guardianship from father to husband. In this way, the Islamic State ensures that responsibility for women’s piety and morality is delegated to accountable male relatives.

Religious ‘Education’

A prominent focus of the Islamic State’s external propaganda has been its commitment to religious education. Beyond the traditional bounds of the classroom, the group’s dawa (proselytization) program also included the indoctrination of adults and teenagers through sharia courses and institutes, Qur’anic recitation competitions, and the religious conversion of captive populations.47 The group sought to transform public spaces into amphitheaters of ideological learning. The most common occurrences were public punishments—amputations, floggings, and executions—to educate on criminality and immorality, as well as dawa caravan events with members giving sermons and distributing pamphlets.48 These activities served to foster a more religiously devout and doctrinally fluent population. Most importantly, the Islamic State explicitly permitted the “cursing of those who promote heresy, debauchery, and infidelity or any of the forbidden acts” (see Item B).49 In a three-page fatwa (the longest in this collection) issued in 2015, the group’s Research and Fatwa Issuing Committee conclude that apostate collaborators and heretics should be cursed.50 Thus, citizens of the caliphate were educated and actively encouraged to monitor others’ behavior and identify those who strayed from or violated the group’s ideological tenets.

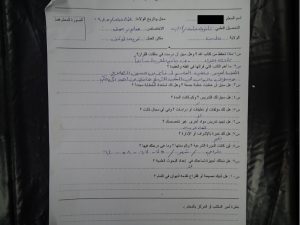

Education—as both an intellectual and social activity—was also an effective recruitment tool for the Islamic State. The reopening of schools, provision of teaching materials, and encouragement of participation in activities filled a significant void in public services in Iraq and Syria prior to the group’s occupation.51 In May 2017, the ‘Department for Education’ published an infographic in Al Naba—the Islamic State’s Arabic-language newsletter—that claimed that over 100,000 male and female students had been taught in its 1,350 schools during the 2015-2016 academic year.52 However, the Islamic State’s curriculum was not a continuation of the prior state models. Contentious or ‘impious’ topics such as literature, history, philosophy, and music were removed and replaced with obligatory classes in Qur’anic memorization, fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), and aqida (creed). As such, the requirements for teachers focused more on doctrinal knowledge than pedagogical qualifications. An undated background-check form for teachers (Item V) demonstrates this shift in required expertise. It asks which parts of the Qur’an have been memorized, which doctrinal text(s) the applicant deems most important, and their grades achieved in a sharia course. Interestingly, the candidate based in al-Waqf village in Aleppo province answers that he has neither teaching qualifications nor experience; yet, he has memorized three parts of the Qur’an and achieved marks in the 50-70 percentiles in his sharia courses.53 This teacher profile reinforces the group’s purpose of education: the transformation of well-rounded classrooms into amphitheaters for ideological indoctrination.

Religious education and outreach under the group’s control did not stop at its Muslim citizens. As the Islamic State swept through northern Iraq during the summer of 2014, it directed its attention to Sinjar—home to the Yazidis, an ethno-religious minority population. Upon capture, residents were given the choice to convert to Islam or face enslavement or death. The Islamic State outlined and justified its strategy of genocide through a series of multilingual pamphlets and articles.54 Yazidis were considered devil-worshippers, and the Islamic State undertook their eradication as its ideological duty.55 The purpose of enslavement for thousands of captive women and children is outlined in a newly declassified directive issued in 2016 by the ‘Delegated Committee’ (Item W). Contrary to the outward propagandistic focus on sexual gratification, the document instead reinforces the purpose of slavery to “restore piety in slaves, teach them the correct doctrine, shari‘i rulings, prayer, and fasting.”56 The directive goes on to outline expected behavior of slaves and ‘owners,’ stating the accommodation requirements: “It is especially not allowed to place her in a house where brothers congregate, and never in a headquarters or similar.”57 The exclusive rights afforded to slave owners echoes the Islamic State’s mahram policy, whereby it is forbidden for women to be viewed by or be in the company of unrelated males. This ruling is explicitly outlined in a letter from the wali of Ninawa (Item X), which forbids the photography and circulation of images of captives among the brothers. It concludes with a recommendation that members “commit to obey God and avoid causes of suspicion and sedition.”58 Thus, the Islamic State justified its campaign of genocide and slavery through its ideological ‘duty’ to proselytization. While conducted through violence, the above documents demonstrate its preoccupation with ‘correct’ treatment, modesty, and ‘decency’ of its members and captives.

Conclusion

Through the imposition of ‘caliphate’-wide regulations and restrictions, the Islamic State created the necessary conditions for its inhabitants to adhere to its extreme interpretation of sharia law and embrace its authoritative implementation. Whether through educational reform, imposition of behavioral strictures, or punishment of violations, the group sought to foster an ideologically pious society, with a disproportionate and explicit focus on women. The framing of these directives is critical to their interpretation and impact. By extolling its virtues, morals, and devotion to scriptural integrity, the Islamic State positioned itself as standing in direct contrast to the perceived corruption and indecency of its rivals. It repeatedly warned against “infidel” and “apostate” influence and celebrated its territorial gains and strategy of enslavement as the enactment of its perceived ‘duty’ of proselytization.

It remains too early to assess the long-term impacts and influence of the group’s piety campaign. Certainly, some female supporters continue to embrace and internalize the group’s ideals of conservative dress, with reports of active policing of others’ attire.59 A significant concern is the possible connection to be made between Islamic State affiliation and religious conservatism post-liberation. For example, while some women shed the shari‘i dress at the earliest opportunity, others, in cities such as Mosul, have been forced to remove the attire on account of security concerns.60 Security actors must avoid interpretation of symbols and acts of religious expression as necessarily signifying ongoing ideological commitment to the terrorist organization. Such forceful imposition or denial of rights risks fueling the same grievances that initially resonated with Islamic State supporters. Going forward, stabilization and reconciliation efforts need to acknowledge a possible shift in liberated communities toward religious piety and conservatism. Breaking away from the ‘us’ and ‘them’ rhetoric and instead fostering inclusivity is a critical first step toward ending ideological outbidding. CTC

Gina Vale is a research fellow at the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) and a Ph.D. candidate in War Studies at King’s College London. Her doctoral research focuses on the impacts of Islamic State governance on women in Iraq and Syria. The documents and findings of this article form part of her ongoing work on this issue. Follow @GinaAVale

All 24 documents described in this article are accessible on the Harmony Program’s page here.

Access each document directly (both original language and English language) by clicking on the images below.

Substantive Notes

[a] Shari‘i is the adjectival form of sharia, meaning ‘legal.’ As the Islamic State sought to justify its rulings on sharia law, documents that stipulate its dress code often refer to women’s full coverage as the “shari‘i hijab.”

[b] A niqab is a veil over the face that leaves only the eyes clear, as distinguished from a hijab (barrier or partition), which is a headscarf used to cover only the head (hair) and neck with the face fully visible. A burqa is the most concealing Islamic garment, which covers the full face and body, often to the ankles. Gina Vale, “Women in Islamic State: From Caliphate to Camps,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, October 2019, p. 3.

[c] Islamic State departments and provincial offices kept rigorous records of their documentation. Here, Fatwa 44 refers to the 44th edict released by the group’s central Research and Fatwa Issuing Committee. Numbering on other documents, such as marriage and birth certificates, can indicate the scale of the group’s management and bureaucratic control of its residents’ lives. Each of the numbered fatwas referred to in this article were released by this Islamic State committee using this numbering system.

[d] A hadith is a record of the words or actions of the Prophet Muhammad. Hadiths are considered a critical source for religious law and moral guidance. However, some scholars have questioned the reliability of some hadiths.

[e] A dishdasha is a men’s ankle-length garment, usually with long sleeves, similar to a robe or tunic. The Islamic state strictly monitored men’s clothing to ensure the length of dishdashas or trousers did not pass the ankle. See “[Raid of the Villages to Spread Guidance],” Islamic State, May 4, 2016.

[f] The author’s examination of Islamic State internal policy documents and external propaganda—as well as fieldwork interviews with civilians who lived under the group’s rule—demonstrates that it did not focus on controlling men’s sexual desire, but instead used its imposition of the shari’i hijab (burqa) to guard against illicit contact and intermixing between the sexes.

[g] The author is not aware of any announcement of its dissolution before this reactivation.

[h] This figure is echoed in recent analysis of an Islamic State registry document that identified 101,850 minors linked to an adult male affiliated with the group. See Daniel Milton and Don Rassler, Minor Misery: What an Islamic State Registry Says About the Challenges of Minors in the Conflict Zone (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2019).

Citations

[1] Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “The Archivist: Unseen Islamic State Financial Accounts for Deir az-Zor Province,” Jihadology, October 5, 2015. See extensive reports on this subject by RAND, including Patrick B. Johnston, Jacob N. Shapiro, Howard J. Shatz, Benjamin Bahney, Danielle F. Jung, Patrick K. Ryan, and Jonathan Wallace, “Foundations of the Islamic State: Management, Money, and Terror in Iraq, 2005–2010,” RAND Corporation, 2016.

[3] Charles C. Caris and Samuel Reynolds, “ISIS Governance in Syria,” Institute for the Study of War, July 2014; Mara Revkin, “ISIS’ Social Contract: What the Islamic State Offers Civilians,” Foreign Affairs, January 10, 2016.

[4] Mara Revkin and William McCants, “Experts Weigh In: Is Islamic State Good at Governing?” Brookings Markaz, November 20, 2015; Zachariah Mampilly, Rebel Rulers: Insurgent Governance and Civilian Life During War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011).

[5] “The Extinction of the Grayzone,” Dabiq, issue 7, February 12, 2015, pp. 54-66.

[6] Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, “[City Charter – Mosul],” June 12, 2014.

[9] Ibid.

[11] Sunan Abi Dawud (4101), Book 34, Hadith 82.

[12] Item C.

[15] Item H.

[16] “News: Hadd of Stoning – Wilayat Ar-Raqqah – Ramadan 20,” Dabiq issue 2, July 27, 2014.

[17] Asaad H. Almohammad and Anne Speckhard, “The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers,” International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism, April 2017; “Women Under ISIL: The Torturers,” Al Jazeera, November 27, 2019.

[18] Carolyn Hoyle, Alexandra Bradford, and Ross Frennett, “Becoming Mulan?: Female Western Migrants to ISIS,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, 2015, p. 12; Meredith Loken and Anna Zelenz, “Explaining Extremism: Western Women in Daesh,” European Journal of International Security 3:1 (2017), pp. 62-63.

[20] “Al-Qaeda in Syria forms female brigades,” Al Arabiya, February 2, 2014.

[22] Vale, “Women in Islamic State,” p. 4.

[24] Item P: “[Written Pledge: Raqqa Province],” NMEC-2017-110372, Islamic State, undated.

[25] For more information on the Islamic State’s focus on legal and bureaucratic transparency, see Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “The Evolution in Islamic State Administration: The Documentary Evidence,” Perspectives on Terrorism 9:4 (2015).

[27] Ibid.

[30] “[Abide in Your Homes],” Al Naba, issue 50, October 13, 2016, p. 15.

[31] Item Q: “[Letter from Abu Fahd al-Tunisi],” NMEC-2015-311501, Islamic State, June 19, 2016.

[32] Ibid.

[34] “[Abu Ali al-Shishani threatens Lebanon: We will kidnap women and children],” Al Arabiya, December 5, 2014.

[36] Bird of Jannah, “Bittersweet – The Life of a Muhajirah (Parts 1-7),” 2014; Erin Marie Saltman and Melanie Smith, “‘Till Martyrdom Do Us Part’: Gender and the ISIS Phenomenon,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, May 2015, pp. 36-43.

[40] See Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, “Archive of Islamic State Administrative Documents – Specimen 13H, 22N, 23N, 36H, 40U,” January 27, 2015; “The Archivist: 26 Unseen Islamic State Administrative Documents: Overview, Translation & Analysis,” Jihadology, August 24, 2015, Specimen S and T.

[44] “[Proof of Birth – Jazirat al-Ramadi court, al-Anbar Province],” Islamic State, December 15, 2016.

[45] Item U.

[46] Item T.

[47] “[The preaching committee in the Islamic state is pleased to announce: An Episode of Memorization of the Holy Qur’an: Ṣalwa, Idlib Province],” Islamic State, July 17, 2013; “[The Atmosphere of ‘Id al-Fiṭr in the City of al-Raqqah],” Islamic State, July 19, 2015.

[48] Roxanne L. Euben, “Spectacles of Sovereignty in Digital Time: ISIS Executions, Visual Rhetoric and Sovereign Power,” Perspectives on Politics 15:4 (2017), pp. 1,007-1,033; “[Dawa Caravan for the Cubs of the Caliphate: Wilayat Ninawa],” Islamic State, April 20, 2015.

[50] Ibid.

[52] “[Ministry of Education During the Academic Year 2015-2016],” Al Naba, issue 79, May 4, 2017, p. 2.

[53] Item V: “Teacher Form [Untitled Document],” NMEC-2016-448192, Islamic State, undated.

[54] “[Fatwa 11 – Question: Is the Yezidi sect in Iraq original disbelievers or apostates?],” Islamic State, August 9, 2014; “Revival of Slavery Before the Hour,” Dabiq, issue 4, October 11, 2014, pp.11-14; “[From the Creator’s Maxims on Captivity and Enslavement],” Islamic State, October 2014.

[55] For more information on the Yazidi genocide and its continuing impacts, see Gina Vale, “Liberated, Not Free: Yazidi Women After Islamic State Captivity,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 31:5 (forthcoming 2020).

[57] Ibid.

Skip to content

Skip to content